Land use questions draw concern in West Richland

Some West Richland, Benton County residents worry about

fate of their land due to an obscure 81-year-old law

Whose land is it

anyway? When it comes to portions of lots in West Richland, it depends on who

you ask.

“Legally, under my

impression, this land has been mine, because Benton County has done all their

due diligence recording their records,” said Pat Carranza, a West Richland

landowner.

Carranza and her

neighbors own property that was originally platted as part of federal land

patents issued by the United States during homesteading in the 1930s as a way

to develop a community around the Hanford nuclear reservation.

“There aren’t too many

areas formed like this. It’s a somewhat unusual critter,” said Kenneth W.

Harper, a Yakima attorney who specializes in land use and zoning, who spoke at

a recent city council hearing on behalf of the city of West Richland.

Harper first got

involved in 2017 when a landowner raised concern after trying to get a building

permit for an area within his legal property description.

“The city’s position

had been, ‘We’d be happy to let you use this land. We just don’t have a process

that confirms whether we continue to claim an interest in that land or we

don’t,’ ” Harper said.

As West Richland tries

to clarify the issue, it has neighbors concerned the city will try to act on

easements written into land disbursements granted back in 1938 as part of the

Small Tract Act.

The legal

interpretation of the federal land patent ownership is now in question, as the

federal government has said it has no interest or decision-making rights on the

future of lots created by land patents. To muddy the waters, it didn’t offer

direction on who could.

Carranza’s 2.3-acre

parcel is close in size to hundreds of other similarly-affected properties near

the Bombing Range Sports Complex and Flat Top Park.

The historical deed for

Carranza’s property dates back to 1956, based on data from the county assessor,

when the borders were solidified by Benton County.

Prior to that, the

federal government had platted the land into lots and access roads, with each

plat reserving 33 feet along one or more of the boundaries for potential

development or use as a right of way.

These became known as

federal patent reservations, or general land office easements, and allowed the

U.S. to retain the right to use the land for any public or private purpose if

needed in the future.

The agency responsible

for dividing the land was the General Land Office, which eventually became part

of the federal Bureau of Land Management. This federal office suggested in 1981

that in areas where no land action had been taken by the city of West Richland,

any future development would fall under state law or city code, not federal

rule.

Harper called it a

“funny intersection of Washington land use versus these fairly archaic deed

reservations, or patent reservations, going back to the ’50s.”

“My deed says it’s

mine, but now the city said it’s going to be up to the homeowner to go file and

change the description,” Carranza said. “One, that’s a lot of money for the

city, and two, the homeowners are not aware of it because they assumed that if

it hasn’t been used since 1981, the city doesn’t have a claim to it.”

Carranza said it’s her

land in particular that’s preventing West Richland from connecting a portion of

South 48th Avenue to Collins Road.

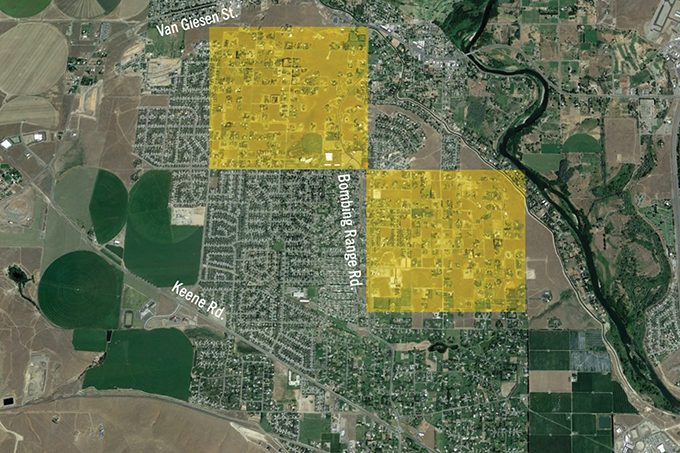

The areas in question

are within city limits and shaped like a square, with borders near Bombing

Range on the east, Belmont Boulevard on the west, Paradise Way on the south and

just north of Flat Top Park to the north.

There are two other

sections affected by potential action: an L-shaped area bordered by Bombing

Range, Northlake Drive, South 38th Avenue, Artemis Ridge Road, Paradise Way and

Northlake Drive, and a smaller, rectangular area that includes 14 lots near

South 38th and Paradise Way. About half this area is within city limits and the

remainder in Benton County.

The city may have once

been interested in developing the affected land, according to a draft

comprehensive plan discussed by the planning commission in 2016. While

questioning whether the federal patents will ever be lifted, the draft document

said, “these patent reservations, and the land divisions from the past,

restrain development capacity in these specific areas.”

The current issue is

now to “explore this more thoroughly, get an understanding from what the record

of what the BLM shows as far as its prior positions, and really apply some

legal reasoning to what the Small Tract Act says, what significance should be

placed on the termination of the classification, and then create a public

process that would allow the community to understand what the city was trying

to do, how it would or would not affect individual parcels, and give the city

council a choice that would, in the staff’s opinion, streamline the city’s

interests in these reservations,” Harper said.

The BLM isn’t expected

to weigh in with an official opinion, and Harper doesn’t expect the process to

change anything as far as what rights of way the city has or has mapped, but

rather to clarify so the issue wouldn’t need to be revisited each time someone

applied for a building permit.

As part of this

process, the West Richland City Council held a public hearing before a packed

house on the issue in November. No city action was taken.

The hearing offered a

chance for residents to weigh in on a potential ordinance to accept or decline

portions of land through an official action called an “offer of dedication.” By

accepting an offer of dedication, portions of land used by homeowners could

become city land instead.

Harper said, “We think

it’s fairly clear that as offers of dedication, the city can come along and

say, ‘We need these as part of our road system. We need these because there’s

public infrastructure. Or we need these because it’s pursuant to an agreement.

Or we don’t need because of this, this, this and this.’ That was what the staff

undertook, saying, ‘What can we get ourselves out of so the public can make use

of it?’”

Any chance of land

being used as an offer of dedication has residents concerned.

“We have paid taxes all

these years on that land,” Carranza said.

Additionally, a number

of landowners complained at the hearing that much of the land up for discussion

is not usable due to being sandy “just like a beach,” too steep for a roadway,

or at a dead-end road that “leads to nowhere.”

A property owner who

spoke at the hearing encouraged the city to look at each lot individually rather

than make a blanket determination on its ability to use the affected land.

Carranza agreed,

adding, “The city needs to look at each lot and determine if there was a right

of way, per the termination notice and/or utility prior to 1981. If it wasn’t used

for that purpose, go to the property owner and say, ‘Hey are you interested in

vacating these lands and not having to pay taxes on them?’ You’ll make money,

in kind of a win-win situation, because if they’re not using it anyway, they

might say, ‘Take it.’ ”

The city intends to

review residents’ public comments from the meeting and those submitted to its

public works director.

“We’d like them to be

as active participants as possible because it does affect individuals’ land.

That’s always going to be a topic and potentially very sensitive, and the more

we can communicate with the public about what we’re doing, and allow them to

respond, I think the better the result will be,” Harper said.

The city has no

timeline for making a decision on an ordinance, or whether this will be the

action taken at all.

“The choice may come

down to doing nothing, and we proceed as we have for the past several decades

with this being a somewhat unclear issue,” Harper said. “Or, council could pass

the ordinance and confirm, to the extent the ordinance does so, the lack of

interest of the city in these rights of way that we don’t have any purpose for.

There’s always a third choice that this could become a topic for further study

because it may be that the council’s not quite prepared to take either of those

two options, they want to hear more from staff or have more consideration of

legal opinions, which would be fine.”

Some landowners hired

an attorney and stated at the hearing their counsel would prefer the city allow

the issue to be handled by the judicial system, not through an ordinance voted

on by the council.

There’s an argument to

be made that deciding the issue with some finality could pave the way for

future requests.

“There’s been a regular

concern brought to the city over whether or not these things can be vacated or

whether the city can take a position of the land to make the use of the land

burdened by these rights of way no longer an interest of the city,” Harper

said. “The city has been in a very difficult spot in terms of answering

questions from the public on what these small tract reservations amount to.”

Still, Carranza

believes it is not for the city to decide. “It’s up to the homeowner because

they actually own that land. The city doesn’t own it. The state doesn’t own it.

It’s the patent property owner’s land and you need to respect their rights,”

she said.