2020 wish list should include making progress on Tri-Cities’ early learning gap

By D. Patrick Jones

In this year-in-review issue, I’d like to look forward – far forward to the impacts of early childhood education in at least a couple decades. This is not the usual stuff of my columns, but the topic has significant implications for the future, including economic ones, of the greater Tri-Cities.

As

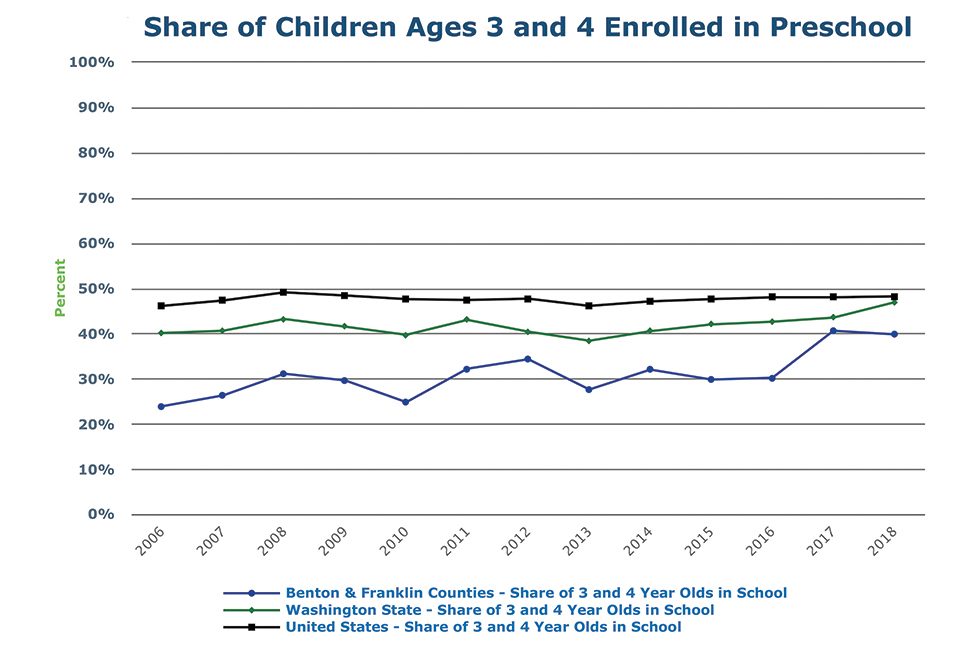

Benton-Franklin Trends data shows, the number of 3- and 4-year-olds enrolled in

Benton and Franklin counties’ preschools is lower than the rest of the state

and in the U.S, over the entire period measured. This is curious outcome for

the wealthiest metro area in Eastern Washington, as measured by median

household income. Specifically, the data measures the share of children ages 3

and 4 who are enrolled in preschool. The estimate for 2018 for the two counties

was 40 percent. In contrast, Washington state reported 47 percent while the

U.S. estimate was 48 percent.

The

data does bear some good news: rates of preschool attendance have gone up

substantially in the greater Tri-Cities since 2005. Cumulative growth in the

two counties since then has been 67 percent. Benton County has shown an

especially strong pulse, with the share of young children attending preschool

rising by 73 percent. Yet, Franklin County’s growth has been much, much lower,

at 15 percent. While it exceeds the improvement in the U.S., its pace is still

below that of the state.

Why

should we care? A moral response is straightforward. Most Americans still hold

the notion that we live in a land of opportunity, if not equal, then somewhat

equalized by access to quality education. This has been shared value for

decades, if not longer. Take away access to good schools and the common ground

we share becomes thinner.

We

know that preschool can be expensive. While we don’t enjoy data on average

costs for unsubsidized preschool in the two counties, we have access to a

“survival budget” in Washington for low-income families. Produced by United Way

of the Pacific Northwest as an alternative to the federal poverty threshold, it

lists the average statewide costs for child care in 2016 at nearly $1,300 a

month for two preschool children. This is clearly out of reach for low-income

families.

And

increasingly, school-age children are coming from lower-income families in the

greater Tri-Cities. A proxy for poverty among families with school-age children

is the count of students who qualify for free and reduced-price lunch. The

Trends data has created an indicator for this that shows over the past 20

years, the share (and count) has risen sharply. During the 1998-99 school year,

the share was 39 percent; for the 2018-19 school year, the share stood at 58

percent. This is a far higher percentage than the state average, and the gap

has widened over time.

Then

there’s the economic argument supplied by two very reputable sources: the

Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank and Noble-prize winning economist James

Heckman.

In a

widely-cited work, two Minneapolis Federal Reserve researchers calculated the

internal rate of return of a preschool program in Ypsilanti, Michigan, that

began in the early 1960s. Data were available about young adult (up to age 27)

outcomes for the children who participated in the program as 3- and

4-year-olds. The researchers’ calculations put the societal return on

investment, compared to a control group, at about 12 percent per year, a very

high rate. Key elements to their calculations were: a substantial decrease in

the societal costs of crime and a substantial increase in the earnings.

Similarly,

Heckman’s statistical review of early childhood programs arrived at a 7 percent

to 10 percent return on investment for disadvantaged children enrolled in

preschool. Early childhood education, Heckman stated, narrows the well-known

achievement gap that begins in school and continues into adult earnings. The

benefits extend beyond earnings. In his review of longitudinal data of a North

Carolina preschool program, Heckman found health advantages, relative to a

control group. The incidence of costly chronic diseases such as hypertension,

heart disease, diabetes and obesity was considerably lower 30 years after a

preschool program.

According

to Heckman, the sooner preschool starts the better. “The highest rate of return

in early childhood development comes from investing as early as possible, from

birth through age 5, in disadvantaged families. Starting at age 3 or 4 is too

little too late, as it fails to recognize that skills beget skills in a

complementary and dynamic way. Efforts should focus on the first years for the

greatest efficiency and effectiveness. The best investment is in quality early

childhood development from birth to five for disadvantaged children and their

families.”

The

Tri-Cities certainly has its share of disadvantaged youth. An outcome measure

of preschool’s impact on a community is the WaKids Kindergarten Readiness

measure. The good news: the share of children in the school districts of the

two counties who meet standards in all six domains of kindergarten readiness

has doubled in the last seven years. The sobering news: that share, 39 percent,

is still several percentage points lower than the Washington average. A

substantial difference exists between the two counties and even more profound

gaps among the three large cities in the counties.

Is an

expansion of early learning opportunities in the greater Tri-Cities on the New

Year’s resolution list of area leaders for 2020? I hope so.

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis.