Home » Pulse of Tri-City travel and tourism industry beats strong

Pulse of Tri-City travel and tourism industry beats strong

March 13, 2019

By D. Patrick Jones

Nearly all

communities want to be popular with visitors. The sentiment has sound economics

behind it since visitors bring new dollars into the local economy. Their visits

catalyze economic transactions that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. There

are, of course, other, non-monetary reasons to embrace visitors, such as

introducing the outside world to the place we call home.

But measuring the

effects of visitors is complicated. Ideally, we would like to know how big a

contribution they make to the local economy. And whether their economic

influence is growing or diminishing. A problem: there are no turnstiles at

county lines asking for visitor status.

To begin, what do

mean by tourism? Following federal standards, the official term is “travel and

tourism.” This definition covers visitors for both business and leisure

reasons. The sectors typically included in travel and tourism are, ranked by

size nationally: non-air transportation, accommodations, air travel, shopping,

food and beverage services, and recreation and entertainment.

Thanks to the U.S.

Department of Commerce, we have a sense of the size of travel and tourism at

the national level. Its measurement is relatively new since these activities

have never been recognized as a unique sector, such as manufacturing or

agriculture. Instead, for the past 20 years the commerce department has

produced a satellite account. This approach pulls effects such as spending or employment

from the regular sectors of our economic accounting via assumptions about what

constitutes resident or visitor activity. What’s a visitor? According to the

feds, someone from 50 or more miles away. As a satellite calculation, the

totals are not used in producing national aggregates such as GDP.

For 2016, the most

recently analyzed year, the Department of Commerce calculated that 3.6 percent

of the U.S. workforce was engaged in travel and tourism. Further, 2.8 percent

of the national GDP was accounted for by visitor spending. These are direct

effects, and do not include the impact of any multiplier calculations.

How much do visitors

spend in Benton and Franklin counties? Nothing is available from the commerce

department for states, metro areas and counties. If we applied national ratios

to the Benton-Franklin metro economy, we’d arrive at nearly $330 million in

“visitor GDP” in 2016 — or about 5,200 jobs, full- or part-time. But that

assumes that travel and tourism in the two counties mirrors national averages.

What is the true effect annually? The short answer is, we don’t know with great

accuracy.

Benton-Franklin

Trends data, however, contains at least two indicators that point to the size

and growth of travel and tourism. The first comes from a Portland research

organization, Dean Runyan & Associates. Much like the Department of Commerce does nationally,

this firm analyzes the visitor economy at the state and local levels. The

methodology, while complicated, is similar to that of the feds.

At the core is an

estimate of visitor spending. Spending has two elements: the volume of visitors

and spending per visitor. Both components are not easy to estimate, with

spending per visitor dependent on a set of surveys that are then applied

broadly. Visitor count estimates largely follow from hotel/motel occupancy

reports, although the growing popularity of private rental homes has

complicated those calculations. Once visitor spending is estimated by sector,

other direct effects, such as employment, can be calculated.

What

does the Trends indicator on direct visitor spending reveal about travel and

tourism in the two counties? For the most recently estimated year, 2017, total

expenditures summed to nearly $625 million. That represents more than a

doubling since 2000. In terms of a growth rate, expenditures have climbed 4.8

percent, compounded annually. This contrasts to a 2.7 percent growth rate

throughout Washington state for nearly the same period, 2000-16.

What

does the lodging tax tell us?

A

less ambitious but accurate measure of travel and tourism can be found in state

taxes levied on the accommodations industry. By definition, the bulk of

activity of hotels is putting “heads in beds.” And it’s unlikely that many of

those heads are local ones. Some of the state collection is returned to the

communities for visitor promotion.

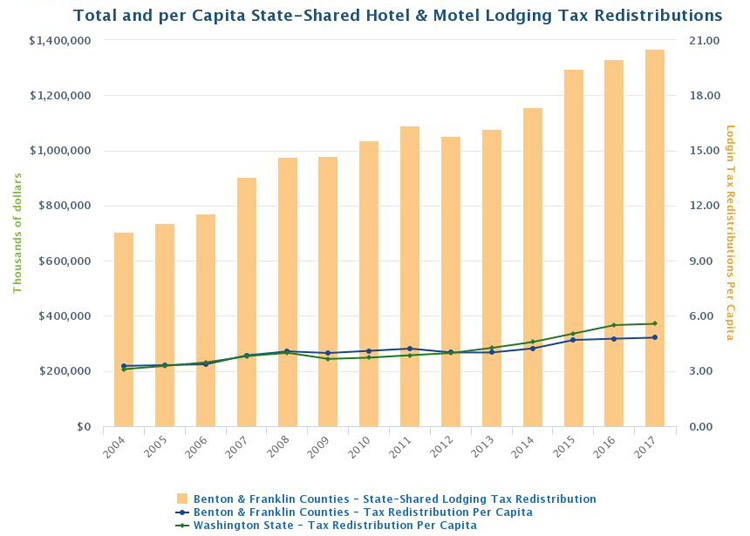

The

Trends indicator on lodging tax redistributions tracks spending at hotels and

motels, using the “state shared” rate (the general sales tax rate). This

component of redistributed lodging taxes is based on a largely a constant rate,

enabling year-to-year comparisons within the accommodation sector. This

approach also enables comparisons to other counties in the state because their

general sales tax rates do not vary much either. Many communities levy

additional taxes on visitors, but this measure excludes them.

What

does the lodging tax redistribution indicator tell us about the growth of

accommodation revenue in the greater Tri-Cities? Strong growth over the

interval, 2004-17: 5.2 percent per year compounded annually. The reflects a

near doubling of accommodation revenues in the past 14 years. The graph shows

the experience of the accommodation industry in all of Washington to be about

the same, with a compounded growth rate at 5.8 percent.

Despite

the difficulties in measurement, it certainly appears that the greater

Tri-Cities is showing a strong pulse in travel and tourism.

D. Patrick Jones is executive director

for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic

Analysis.

Local News Hospitality & Meetings

KEYWORDS march 2019