Home » Tri-City finance sector rooted in supportive economy

Tri-City finance sector rooted in supportive economy

July 15, 2019

By D. Patrick Jones

Nearly every reader of this column has a relationship with a bank, credit union, mortgage lender or maybe a combination. The financial system of the U.S. is widely celebrated for contributing to our country’s economic success. What’s true nationally is true locally.

Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis

According to data from Benton-Franklin

Trends, the finance sector doesn’t appear in any of the measures because, while

important, it doesn’t figure among the top five, measured by dollars or staff

size. I’ll fill in a the picture using data from other sources.

The intent is to assess the growth of

these businesses over the past few years and get a sense their health.

At the local level, banks, mortgage lenders

and credit unions make their living off the spread between rates of deposit and

lending. To make loans, one needs deposits (unless we’re talking about an

investment bank pre-2008).

Thanks to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, we have a good idea of what the ability of local institutions has been to attract deposits in recent years. The FDIC publishes an annual snapshot from June of every year. In 2018, the total for FDIC-insured institutions was $3.1 billion. In 2013, the total was $2.6 billion. That translates into a gain of 20 percent, a pretty good jump over a six-year period. It’s worth noting that the similar total in the entire state increased by 37 percent over the same period.

Now to lending. Financial sector companies, “credit intermediaries,” need a robust economy to be able to loan at levels that compensate for the costs of doing business. They are not the “drivers” of the economy, but key facilitators. To gauge the experience of the finance sector, we used the interval cited above, starting in 2013. That year generally marked the trough of recent business activity in the greater Tri-Cities, and not 2009. The unemployment rate peaked in 2012, but employment and metro gross domestic product bottomed in 2013. We’ll assume that the recovery started after 2013.

To assess potential lending strength, let’s consider some aggregate forces in the economy that determine loan demand. Ideally, we’d like to have current data, but that’s not the way government information-gathering usually works. But we can peer into the recent past and get a sense of what might be happening at the moment because these trends typically move slowly.

Employment in the two counties has

gained 16,000 since 2013. Most recently, between 2017-18, more than 2,500 jobs

were created, or 1.9 percent growth. That’s a healthy clip, although it’s

worthwhile noting that statewide, employment expanded by 2.3 percent over the

same time period. More jobs lead to more transactions in the finance sector,

either directly, such as mortgage and car loans, or indirectly such as loans to

consumer-facing businesses.

While new jobs

provide an aggregate lift, so do wages. In other words, a middle value of

earnings across the local economy. How have earnings fared since the trough?

There’s been a gain of about $4,800, or 8.5 percent, since 2013. Nearly a third

of that, $1,500, came about in 2018. That represents a healthy 2.9 percent

increase. Again, the state outperformed the Tri-Cities, rising 5.1 percent over

the same interval. The effects of bigger paychecks actually are larger than

those of new jobs, because everyone employed enjoys the gains.

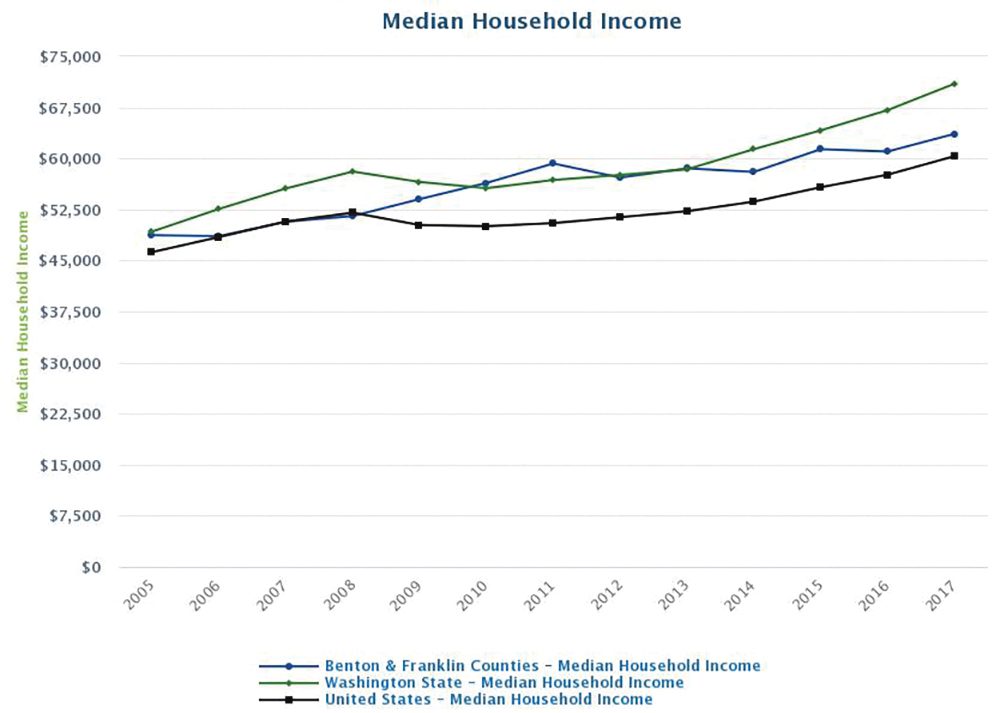

A final gauge of

the aggregate lending environment comes from income, specifically median

household income. This is a more complete measure of consumer spending power,

because it includes investment returns, as well as federal transfer payments

(Social Security, veterans payments, etc.). Since the 2013 trough, there’s been

a gain in Tri-Cities of nearly $5,200, or 9 percent. The most recent period,

2017, accounted for nearly half of that amount, or 4.3 percent increase. The

state’s increase was higher, at 5.8 percent. The consequences of a jump in

median household income are the same as for average wages.

These three broad measures of the Tri-City economy point to good tailwinds for the finance sector. The tailwinds, however, do not show up in the labor counts, as the number of people employed in the sector has stayed flat since 2013. Technological change is coursing through the finance world, allowing the businesses to do more with the same head counts.

We do know that FDIC-insured

institutions have experienced sound growth over the last six years. Given the

strength of the economy, that’s no surprise.

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis.

Local News Banking & Investments

KEYWORDS july 2019