Home » Finding young professionals in the Tri-Cities

Finding young professionals in the Tri-Cities

September 12, 2019

By D. Patrick Jones

What do we know about the presence of young professionals in the Tri-City area workforce? From a data perspective, not enough.

But first let’s define our terms.

D. Patrick Jones,

D. Patrick Jones,

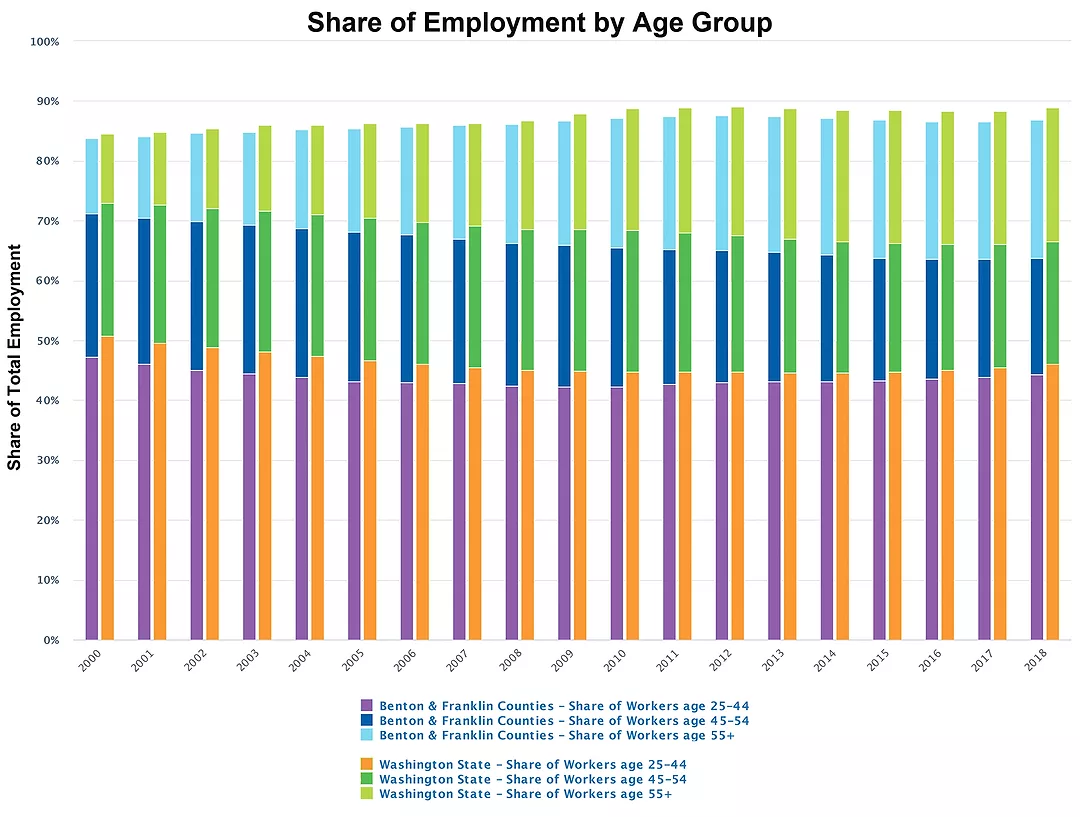

What constitutes “young,” for example? Data to answer that question is available, if we agree on a definition. For example, consider Benton-Franklin Trends indicator, “Share of the Workforce by Age.”

Here, “young” might be defined as those between 25 and 44. The current share amounts to 44 percent, the largest in the two-county workforce. This is a little below the state average. And the share of this age cohort has slipped over the past 17 years, from about 47 percent. But the state’s share has declined by a slightly larger percentage. Note that this doesn’t mean the count has slipped, just the shares.

One might object that people in their 40s are no longer young. (Of course, this boomer sees it differently.)

We can delve into the Census data for this indicator to find narrower age bands. Consider the 25-34 group. We shouldn’t expect many arguments about a good fit of this age group to the notion of young.

For the 2014-17 period, this group claimed, on average, 21 percent of all jobs in the Tri-Cities. Across the state, by contrast, it was responsible for about 24 percent of all jobs. So by that measure, the labor force here is a bit “less young.”

A more difficult consideration is what is a “professional”? Traditionally, we might have looked to those “white collar” jobs, or office jobs that require a certain amount of independence or management authority. That descriptor seems a bit dated now, given the fluidity of the work environment, not to mention changing dress codes.

But we can track, thanks to Washington’s Employment Security Department, the number of jobs by occupation by metro area.

For purposes of this column, I will count any occupation that requires an associate degree or above as a “professional” job. I realize that many other occupations, such as the trades, might consider themselves professional in their skills. But adopting a formal education threshold is a relatively straightforward solution to a messy definitional issue.

Some of the prominent groups of occupations folded into this definition are: most managers, all computer specialties, teachers (K-12 and higher ed), most health care workers, many in finance and those who are labeled “professions,” such as lawyers, accountants and engineers, in the official statistics.

The 2019 ESD count listed nearly 400 professions present in the Tri-Cities. Professional jobs amounted to a little over 23,000, or about 23 percent of the workforce. A similar look at Washington state data shows that about 29 percent of its workforce might be considered professional. So this type of worker is not represented as broadly here, reflecting an economy with a strong agricultural tilt.

Ideally, I would like to match up Tri-Cities’ professional jobs to certain age groups, be they 25-44 or 25-34. The readily available data simply can’t do that for us.

So what can we conclude from the stats? It seems clear the Tri-City labor force holds a good percentage of professionals (as defined here) who are also young. We would expect that of any metro area with nearly 300,000. We also know that the two counties are considerably younger than the state, as seen in the Trends’ median age indicator.

But we also know that the share of the population here with an associate degree or higher is appreciably lower than the nation or the state.

In 2017, for example, Trends indicators depicting those with associate, bachelor’s or higher degrees show that the total share amounted to 34.6 percent, versus the U.S. share of 40.3 percent. (The equivalent for Washington was higher yet.)

In the end, young professionals are associated with an urban environment, as professional jobs are increasingly found in cities. Certainly the area has cities. Of course, the Tri-Cities just doesn’t sport a district remotely resembling Seattle’s South Lake Union, where there it seems nothing but young professionals inhabit the buildings. To be able to claim a larger professional workforce that is also young, the Tri-Cities would profit from a greater urban sense of place. And to populate an expanded urban environment with young professionals, overall education levels here will need to climb.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News Leadership Development

KEYWORDS september 2019