Home » Say goodbye to coal in 2020 and hello to clean energy investments

Say goodbye to coal in 2020 and hello to clean energy investments

December 13, 2019

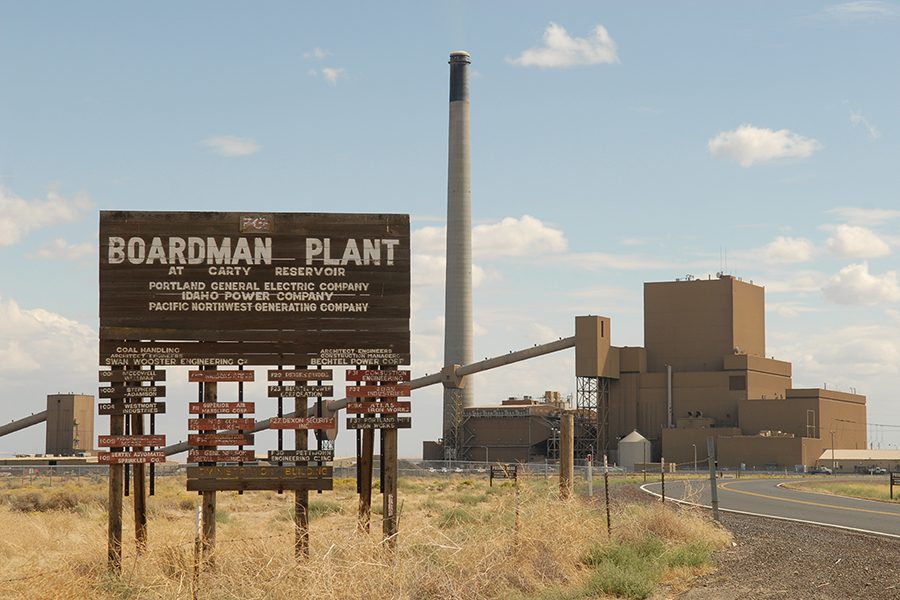

The Northwest will take a giant step toward a future

powered by cleaner energy in 2020 as four coal-burning plants go offline,

including one 50 miles southwest of the Tri-Cities.

Portland General Electric will complete its 10-year plan

to mothball its 600-megawatt coal plant at the Port of Morrow in Boardman. Two

of four coal plants at Colstrip, Montana, will shut down by early 2020.

And Canadian power giant TransAlta will shut down one of

two coal-burning plants at Centralia, Washington.

“We’re pretty thrilled with the way things are going,”

said Sean O’Leary of the Northwest Energy Coalition, which joined the push to

end reliance on coal-generated power more than a decade ago.

O’Leary notes the shutdowns aren’t the economic

catastrophe people imagined. The intervening decade has seen investments in

wind, solar and high-efficiency gas projects designed to meet climate goals in

both Washington and Oregon.

“It’s a really powerful economic story,” he said.

PGE’s move to stop burning coal in Boardman, accompanied

by new investments in wind, solar and

battery power, is of special interest to the Mid-Columbia.

Tri-City economic development officials are counting on

clean energy to help power the local economy in the decades to come.

In December, MyTri 2030 identified clean energy a top

economic priority for the region. MyTri 2030 is an initiative of the Tri-City

business community to identify economic drivers that capitalize on local

interests and resources.

“The fact is the Tri-Cities is perfectly positioned to

lead the world into a clean energy future,” said Ashley Stubbs, communications

and investor relations director for the Tri-City Development Council.

Public vs. private utilities

As a private, investor-owned company, PGE is distinct from

the public utilities that serve the Tri-Cities.

But they’re all connected to some degree by the power grid

and a common partner. The Bonneville Power Administration buys power produced

by the region’s dams as well as Energy Northwest’s Columbia Generating Station

nuclear plant north of Richland.

BPA sells power to the Benton and Franklin public

utilities, Richland’s energy utility and other customers.

PGE is a customer of BPA’s transmission system and has a

five-year contract to buy hydropower from the federal marketing agency.

The long farewell

Under pressure from environmental groups, including the

Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal initiative, PGE announced in 2010 it would stop

burning coal at Boardman by 2020, 20 years ahead of the planned 2040 shutdown.

The company made interim upgrades to the plant, but the

early shutdown helped it avoid hundreds of millions of dollars in costs

associated with longer-term emission controls.

The shutdown could have dealt a significant economic blow

to Boardman, where the plant is a major property taxpayer and employer.

Instead, the intervening decade gave the community,

company and employees time to adjust, lessening the impact.

“The 10-year lead time gave everyone time to plan,” said

Steve Corson, PGE spokesman.

The plant’s payroll is down to 73, from 115, as workers

retired or moved. The utility isn’t quitting the region. It has invested in new

facilities in eastern Washington and Oregon to power the 50-plus communities it

serves in the Willamette Valley:

• 2014: PGE completed the $500 million Tucannon River Wind

Farm on 20,000 acres near Dayton. Tucannon’s 116 turbines generate an average

of 101 megawatts, enough to power 84,000 homes.

• 2016: Carty Generating

Station, fueled by natural gas, went online in Boardman in July. The

440-megawatt plant employs 20 and powers 300,000 homes. Carty joined two

existing gas units at Boardman’s Coyote Springs complex. Developed in the 1990s

and early 2000s, Coyote Springs generates nearly 500 megawatts.

• 2019: PGE and Florida-based

NextEra Energy Resources commenced development of the Wheatridge Renewable

Energy Facility near Boardman after nine years of planning. The project will

produce 380 megawatts of solar, wind and battery energy. Construction will

create 300 jobs. The facility will employ about 10. PGE’s share of the project

is reportedly $160 million.

Shutting down a plant

The coal plant produces power for PGE and its partner,

Idaho Power, by burning coal mined at the Powder River Basin on the

Montana-Wyoming border and hauled in by train.

PGE outlined the complex shutdown process in plans filed

with Oregon regulators. It will shut down by the end of 2020, but the exact

date will be a function of logistics, including the amount of coal on hand.

It is leaving the door open to reusing the plant, possibly

to produce power or as an element of the region’s power grid.

Corson said coal-specific equipment will be removed, but

PGE is interested in exploring reuse. “The plant is relatively young and fully

functional as a resource. Could you run it on alternative fuel that would be

non-emitting from a greenhouse gas standpoint? That’s a possibility that we

want to explore,” he said.

What’s next?

Washington and Oregon both have clean energy requirements

that will continue driving investment in renewable energy facilities, including

wind farms, solar stations and more.

Washington adopted renewable energy standards in 2006.

The governor’s 2018 Clean Energy Transformation Act

requires Washington to be carbon free by 2045.

Oregon’s Renewable Portfolio Standards mandate that 50

percent of its electricity must come from renewable resources by 2040 and that

coal powered electricity must be phased out by 2030.

That sets the stage for additional investments,

potentially in the Mid-Columbia.

PGE’s Wheatridge Renewable Energy Facility announced in

November is a good example.

When built, Wheatridge will boast 300 megawatts of wind

energy powered by 120 GE turbines and 50 megawatts of solar power.

The battery component will be required to deliver 30

megawatts of continuous energy for four hours. The project was conceived to run

on lithium ion battery technology but a final decision hasn’t been made.

PGE and NextEra will split ownership of various aspects of

Wheatridge, but the utility will buy all of its output.

There could be more to come.

PGE wants to add 150 megawatts of renewable energy by

2023. The 2019 resource plan is pending before the Oregon Public Utility

Commission. If approved, the company soon will flesh out how and where it will

accomplish that. Corson didn’t rule out eastern Oregon.

“It’s a place with a lot of

sun,” he said.

Local News Energy

KEYWORDS december 2019