Home » Tri-City manufacturing fares well in era of Covid-19

Tri-City manufacturing fares well in era of Covid-19

June 12, 2020

Manufacturing in the greater Tri-Cities certainly isn’t the largest sector. By recent (2018) average annual headcount, it ranks ninth, with about 8,200 workers.

If you’re wondering, government – at all levels – is largest.

Manufacturing also isn’t a greater provider of high wages in the local economy. In 2018, it paid an annual wage of nearly $50,000. The average annual wage for the entire economy was slightly higher, at $51,619.

Yet, on a different measure, growth, it scores high. Manufacturing has been the gangly teenager of the economy in the two counties. Of the 10 largest sectors by headcount, manufacturing has grown nearly the fastest. Between 2003-18, jobs increased cumulatively 49 percent. Only health care grew faster, doubling over the period.

Where does manufacturing reside in the two counties? Largely in agricultural processing. In Benton County food and beverage manufacturing made up nearly two-thirds of all manufacturing employment in 2018. In Franklin County the same two industries constituted 75 percent of all manufacturing employment. In Franklin County, nearly all industry jobs are found in food processing. In Benton County, however, about 45 percent of the industry jobs can be attributed to beverage production.

How has local manufacturing fared in the wake of state policies to control the Covid-19 outbreak? The emphasis on food and beverage has meant that most manufacturing jobs have not been lost over the past two months. This can be captured by two measures. The first is initial claims for unemployment benefits. Through May 23, cumulative initial claims by manufacturing workers have amounted to slightly more than 2,150. As a percentage of the workforce (measured in 2018 terms), manufacturing has suffered a 26 percent job loss. Only two of the largest 10 sectors have experienced lower job loss rates – professional and technical services, as well as waste services.

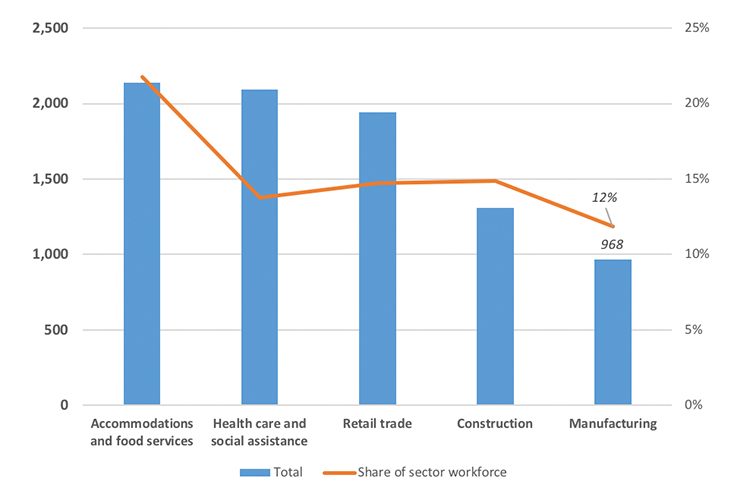

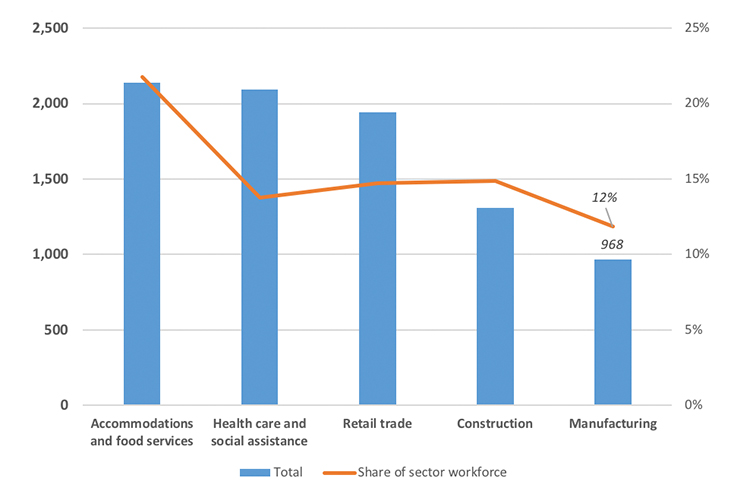

Continuing claims for unemployment benefits gives a different measure, really a snapshot as of May 23, of the current number unemployed. At that date, the total number of workers who had received and were continuing to receive benefits was about 14,000. Typically, the numbers are much lower than the cumulative claims over this short an interval (10 weeks). For example, the cumulative initial claims count on May 23 was slightly more than 36,000. Why the difference? People roll off the unemployment roster, a dynamic not captured by cumulative initial claims.

Local manufacturing ranked fifth for overall job losses at the end of May. Compared to the leading contributor for job losses, health care and social assistance, manufacturing was a distant fifth. And as a share of all those employed in the industry in 2018, manufacturing showed losses of 11 percent, also fifth lowest among the five largest sectors with losses.

Washington state’s Phase 1 rules allow all food and beverage manufacturing to continue production, and given the makeup of local manufacturing, this has largely benefited the Tri Cities. Of course, if outbreaks occur, then public health authorities will have no choice but to intervene. They might shut down a plant for a while, as they did Tyson’s Wallula plant and fruit packers in Yakima County. At the time of this writing, however, no such episode has been observed in Benton and Franklin counties.

Once the two counties are able to move to Phase 2 reopening, then all manufacturing will be allowed to restart. Whether all the jobs come back is unknown. Markets may have weakened and supply chains may have been dented, if not broken.

While manufacturing doesn’t land in the top 5 sectors by workforce or earnings, it provides great benefits to the greater Tri-Cities, if only for one reason. Nearly all of its production is sent out of county and a significant share overseas. This flow of goods implies that manufacturing sales represent “new dollars” in the local economy. That is always something one likes to see in an assessment of the local economy.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News Manufacturing

KEYWORDS june 2020