Home » Manufacturing in the greater

Tri-Cities is solid but hardly diversified

Tri-Cities is solid but hardly diversified

Manufacturing in the greater <br>Tri-Cities is solid but hardly diversified

June 14, 2021

Unique among nearly all Eastern Washington population centers, the greater Tri-City manufacturing sector doesn’t land in the top five sectors. By headcount, it usually ranks fifth in Eastern Washington. Should we be worried? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

One reason for the difference from neighboring economies lies in the presence a large sector known as Administrative & Waste Services. Benton-Franklin Tends data shows slightly more than 9% of the workforce in the two counties fell into this sector in 2019, the most recent full year of data, placing it fifth. Its share of the Benton County workforce was considerably higher, at 11.4%.

This category refers to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Hanford cleanup work.

A major argument made for manufacturing rests in the wages it pays.

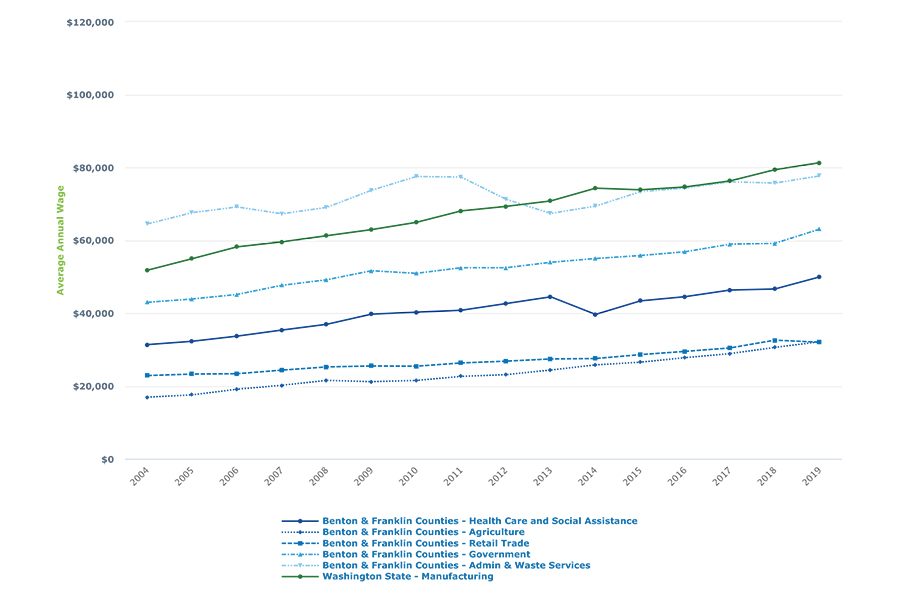

They are typically quite high. But in the Tri-Cities, as Trends data reveals, the highest paying of the largest five sectors, by headcount, is Administrative & Waste Services. Its 2019 average annual wage was nearly $78,000. This result places it far higher than the next-ranked of the top five sectors, government.

The displacement of manufacturing by this sector isn’t a bad problem to have. Especially since manufacturing wages here are considerably below those of Administrative & Waste Services: about $59,000 in Benton County and $45,500 in Franklin in 2019. These results are only slightly above the annual average for that year for the entire economy, according to Trends data.

On the other hand, manufacturing claims the virtue, along with tourist-based activities, as a complete exporter, here defined as shipping product beyond the borders of the two counties. Very little manufactured products in the Tri-Cities stay in the Tri-Cities. As an exporter, manufacturing’s revenues come entirely from outside the area.

Put differently, its revenues represent “new money” to the area.

It won’t surprise anybody to learn that manufacturing here is firmly anchored by agricultural processing.

From 2019 data, we know that about 5,790 workers punched a clock at agricultural processing plants. That represented 70% of all manufacturing jobs in the two counties.

In no other Eastern Washington metro areas did agricultural processing loom so large among manufacturing activities. The closest was Grant County, at 48%.

Agricultural processing in Yakima County took up 40% of all manufacturing jobs. Significantly, over the past decade, agricultural processing has become a bit more important, as it made up 68% of all manufacturing jobs in 2010.

The predominance of agriculture in the manufacturing mix here is understandable, given the bounty of field crops, animal husbandry, orchards and vines in the two counties. It is good that much of this bounty doesn’t leave the area at the farm gate. Think of potatoes becoming french fries, grapes becoming wine, fresh beans becoming frozen ones.

At a certain point of concentration, however, a worry about diversification starts to creep in.

Modern portfolio theory and common sense point toward an optimal mix of activities where one sector doesn’t completely dominate. It’s a risk reduction strategy, although it appears unlikely that the foods produced here will not fall out of favor anytime soon. From a longer-term perspective, it strikes this observer that the growth of other manufacturing industries will help reduce risk. And perhaps raise manufacturing wages.

What might these be? If we follow the strategy of building on existing industries, they could be electronic device and fabricated metal manufacturing jobs in Benton County. On the east side of the Columbia River, they could be jobs based on non-metal mineral production.

Of course, others might enter the mix via recruitment of new industries to the two counties. Perhaps some of the coveted “advanced manufacturing” firms might show on the banks of either county.

Recruiting manufacturing plants is hardly easy. But it does happen, and the U.S. Southwest has, according to recent coverage in the Wall Street Journal, captured 30% of recent manufacturing jobs created in the entire country. Automobile assembly, computer chip fabrication and medical devices have all recently appeared on the manufacturing scene in the states of Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.

Proximity to California doesn’t hurt. Nor does the cocktail of state and local incentives these states pour out to potential investors. But workforce matters and to this observer, the greater Tri-Cities can tout its labor.

Cost of living likely is just as competitive here as in the Southwest. And cities there can’t claim a leg up on Benton and Franklin counties when it comes to annual days of sunshine.

I’m not suggesting that diversifying the manufacturing base will be easy. But I hope it will become a point of conversation here. The reshoring phenomenon of U.S. manufacturing is happening. Supply chains will become shorter. How can the greater Tri-Cities contribute to and profit from these positive developments?

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Manufacturing

KEYWORDS june 2021