Home » The pandemic was not kind to student learning

The pandemic was not kind to student learning

September 12, 2022

The grim scorecard of Covid-19 in the U.S. is responsible for over 1 million deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention Tracker. In addition to deaths, the pandemic has left a trail of injuries and insults: long-term disability, early retirement, hundreds of thousands of years of time unemployed, not to mention countless examples of unraveled civil discourse.

Fractious discussions about how schools best respond to the virus, here and throughout our state, are good examples of the last effect.

The evidence of the pandemic on student learning has now started to come in. As you may guess, it’s not a pretty picture.

Nationwide, elementary school math and reading scores fell to levels unseen 32 years, according to the recently released National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test, known as the “nation’s report card.” Average scores for 9-year-old students in 2022 declined 5 points in reading and 7 points in mathematics compared to 2020.

Consider Washington state test scores. As parents (and students) know, the Smarter Balanced Assessments (SBA) were not administered in the spring of 2020. They were, however, given in 2021, although in September.

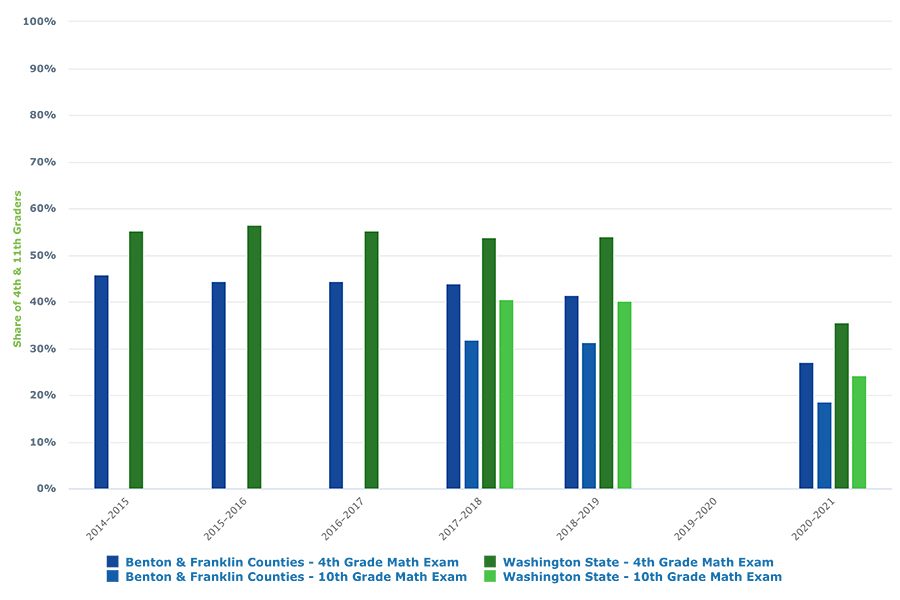

Benton-Franklin Trends tracks two of the assessments. The accompanying chart is the latest view of the math SBA. The indicator shows the share of students meeting standard (levels 3 or 4). Initially, the data track only the fourth-grade test; school year 2017-18 added the tenth-grade exam.

A quick takeaway: the scores, here and statewide, are low, revealing an average far less than half of public school fourth-graders meeting standards over the first five years of the math SBA.

Another takeaway: Washington average shares were higher than the average of the districts in the two counties, by about 10 percentage points.

A third takeaway: the share of tenth-graders meeting standards has been considerably lower than for fourth-graders, both for area public schools and throughout the state.

The results from the 2020-21 school year (taken last September) depress the five-year average further.

The overall average for area public school tenth-graders meeting SBA math standards plummeted to about 19%. Fourth-graders fared better, at 27%, but were still far below the average of the prior five years, 44%.

As Trends data reveals, the greater Tri-Cities’ experience wasn’t unique. Washington averages plunged as well in the first post-pandemic assessment. The statewide share of students meeting tenth-grade math standards was 24%, down substantially from the pre-pandemic average of 40%.

The picture for area K-12 students is a bit brighter for the English Language Assessment (ELA). This is viewable on the Trends website at bentonfranklintrends.org.

Students, local and statewide, typically have met standards at higher rates than for the math SBA. The pre-pandemic average share for area tenth-graders meeting standards was over 60%. But local school shares dropped by about one third in the fall 2021 assessment, or to 43% for the tenth-grade ELA. These most recent values are still below the Washington average, albeit with a smaller gap than in math.

Undoubtedly, the summer slump that afflicts knowledge levels of most U.S. students in early fall was partly at work.

Among the developed countries tracked by the Organization of Economic Cooperation & Development, the U.S. educational calendar traditionally has sported one of the longest summer vacations – at least 10 weeks and often longer, depending on the district.

Contrast that to Germany and the U.K., at six weeks, Denmark at seven weeks, and France and Norway at eight weeks. Not surprisingly, fall greets U.S. students with a reminder of how much was forgotten over the summer.

SBA results from this past spring won’t be posted for a few months. Did area students catch up to pre-pandemic performance over last school year? The likely answer is no, but some progress also was likely. Whether that progress was substantial or slight remains an open question, however.

If the answer is slight, the repercussions for especially older students are concerning. For those who haven’t gone on to some post-secondary education, there seems little chance of catching up. For those who have, some make-up classes may be in order, if a struggle in many core classes of a bachelor’s degree are to be avoided.

In fact, Eastern Washington University instructors have observed an increase in math-challenged students who graduated from high school in the past two years.

Younger students should have time to regain grade-level competencies, but not without extra effort from schools, students and parents.

Longer-term, one can only hope that our school systems, both K-12 and higher ed, can bring our students back to expected grade level competencies. The stakes are high for the futures of our young people. They are also high for the economy of the greater Tri-Cities.

According to data the Institute compiles for Vitals put out by the AWB Institute, the greater Tri-Cities is home to the largest concentration of STEM jobs in the state – as a share of the workforce. If a goal of local leaders is grow its own talent, future engineers, scientists and health professionals will need to be proficient in both math and language skills.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Education & Training

KEYWORDS september 2022