Home » Health care sector continues to grow, but is health of population improving?

Health care sector continues to grow, but is health of population improving?

February 10, 2023

In prior years, this column’s annual look at health care in the greater Tri-Cities has treated the sector as a business.

On the basis of a key indicator in Benton-Franklin Trends that tracks employment by sector, we’ve pointed out that health care and social assistance in the two counties is now the second-largest source of employment. As of 2021, the sector represented nearly one out of every seven jobs here.

It wasn’t always so. After the turn of the millennium, the labor force in the sector took up about 1 out of every 12 jobs. Its remarkable growth over the past 20 years has been the largest and fastest of all the major 19 sectors of the local economy.

We also have pointed out that this robust growth is reflected in current job openings. The Washington Employment Security Department posts a monthly “top 25” openings.

Nursing usually occupies the top spot, as it does throughout most of the state. Yet, other health occupations typically populate the top 25 list for the two counties. For the most recent available month, December, the list for Benton County included nine occupations and in Franklin, five.

But let’s expand our field of vision. A health care sector exists, one hopes, to keep people healthy. The single most important metric of the health of a population is its life expectancy. (It would be better if we could adjust the years for quality of life, but that’s beyond the typical calculations at the local level of this key metric.)

How has the greater Tri-Cities fared over the years by this measure?

Not bad at all. Until 2020, that is.

Trends data, “Life Expectancy at Birth,” clearly shows that the average number of years expected here has steadily increased over time. Additionally, it has always been higher than for the average American, and in many years than for the average Washingtonian. The decline, however, between 2020 and pre-pandemic 2019 is startling.

The U.S. expected lifespan for the newly-born dropped by 1.4 years. In the greater Tri-Cities – by a full two years. Washington overall fared the best, with a decline of 0.7 years. This puts the 2020 outlook for newborns in the greater Tri-Cities at a level last seen 12 years prior, 2008.

What happened? We don’t know exactly, but if the local pattern of deaths from the pandemic matches that of the state, some clues emerge.

The Washington Department of Health (DOH) publishes a biweekly report on cumulative case counts, hospitalizations and deaths from Covid-19 from the start of the pandemic. The most recent data show a wide disparity in all three measures by race and ethnicity.

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders and American Indian/Alaska Natives clearly have been the hardest hit. But as Trends data shows, these two groups do not make up much of the area’s population.

Hispanic/Latinos, of course, do – by more than one third in 2021. And the experience with the pandemic of this population statewide was far less favorable than for the average Washingtonian.

Cumulative case rates have been about the same, according to Washington DOH. Hospitalizations, however, have been over 40% higher and age-adjusted death rates nearly double the statewide average. I doubt that the experience here has been much different.

A lower immunization rate among Hispanics likely stands behind this widely disparate outcome. Research shows a clear connection between higher immunization rates and lower hospitalization and death rates. But lower immunizations reflect a larger phenomenon in the health care system in the greater Tri-Cities. In a word, the local Hispanic/Latino community appears underserved.

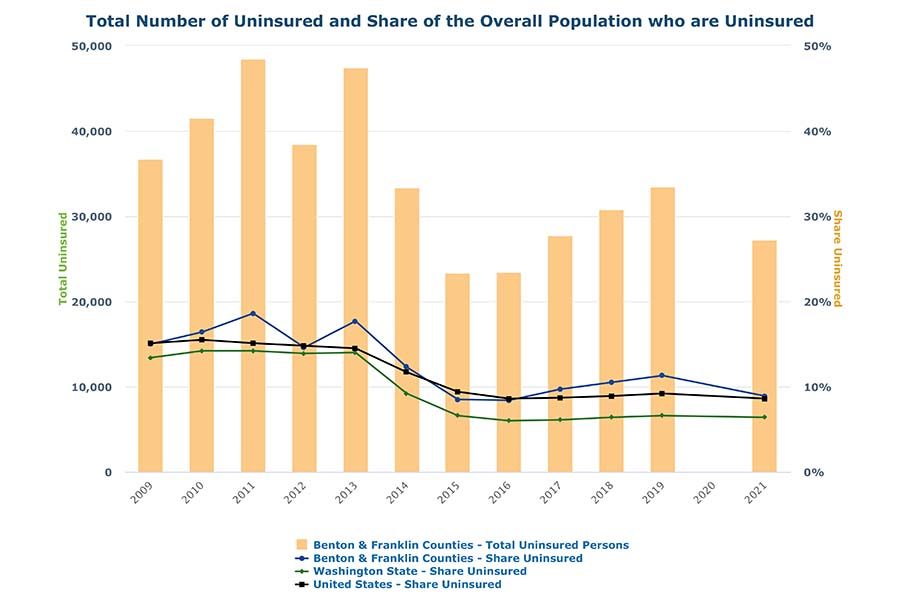

We see this primarily in supplemental data that tracks health care insurance coverage. Data makes clear that the rate of local residents without health insurance has placed higher than in the U.S. and Washington for nearly all years tracked.

At the inception of the Affordable Care Act, 2015, the local rate of the uninsured dipped significantly to match or even show a lower percentage than the nation. But since then, the local rate has climbed. (2020 data is unavailable from Census, as the pandemic curtailed response rates enough for the Bureau to not release them.)

Health insurance status provides a good proxy for the likelihood of encounters, especially on a somewhat regular basis, with health care providers. Without encounters, preventive measures such as immunizations simply aren’t commonplace, let alone habit.

When the supplemental data found in the source table to this indicator are examined, it is clear that the pandemic experience of people of color is mirrored in local health insurance rates.

The overall average rate of the uninsured in the two counties over the 2017-21 period was 9.6%. For the large Hispanic/Latino population nearly twice as much, at 18.7%. This high rate of Hispanic/Latinos was, unfortunately, not unique to the greater Tri-Cities; nearly all central Washington counties show this disparity.

The gap between the two rates raises the question of why?

Are employers of largely Hispanic/Latino staff not offering health insurance? Is the Washington state exchange, Healthplanfinder, too complex or not amenable to Spanish speakers? Is there a cultural hesitation to engage in preventive medicine?

Whatever the reasons, let us hope for the sake of the future of the Tri-Cities that this group is not excluded from the first-class health care system here.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Health Care Opinion

KEYWORDS february 2023