Home » Higher education in Tri-Cities isn’t keeping pace with local market’s needs

Higher education in Tri-Cities isn’t keeping pace with local market’s needs

September 13, 2018

By D. Patrick Jones

The Tri-Cities sport an enviable concentration of talent in science and technology. In economic statistics, most of these professionals show up in the sector “Professional & Technical Services”. The other sectors that contain tech workers are Information and Manufacturing. While firms of lawyers and accountants make up part of the first sector, the largest statewide components are engineers and computer programming businesses. Data are not available for the Tri Cities to know whether the composition here mirrors that of the state. But we do know that the industry “other biological and physical research” is also a part of the sector.

Average employment data for 2017 show Professional & Technical Services to be the 6th large sector in the metro area. In contrast, the Information sector is small, with the traditional industries of print media and telecommunications dominating. While there are a few area firms engaged in advanced manufacturing, the bulk of local manufacturing jobs rest in agricultural processing.

Firms, of course, are made up of different occupations. Another route to understand science and technology in the area is through the lens of STEM occupations, or science, technology, engineering and math. A relevant question for both business and education leaders is where local STEM workers come from. We don’t know to what degree the seats filled by STEM professionals carry a “made in the Tri-Cities” label. But it is this author’s guess that local leaders (and parents) would like to see more of the label.

One way to fill STEM occupations with home-grown talent is for local high school graduates to attend WSU Tri-Cities, earn one of several degree options in engineering and computer science, then find a local job. Another is for high school grads to leave the area for their university education, then return. In both cases, success in acquiring the necessary degree will be greatly enhanced by a good start in grades K-12. Let’s delve a little a bit into what Benton Franklin Trends say about that experience.

First, let’s applaud our school districts for helping more students complete high school. As indicator 4.2.5 the Trends reveals, the last seven years has shown a jump in the 5-year completion rate, from 75% to 82% for the two counties. Yet, this rate just equals the Washington average. And a graduation rate in the low 80% range implies that nearly one fifth of kids in the public education system are not graduating.

Beyond graduating, how are area students performing on the math and science assessments? While this aspect of Washington’s public K-12 system is in flux, students are still taking the tests, now known as the Smarter Balanced Assessments. For the most recently available year, 2016-2017, 44% and 21% of 4th and 11th graders, respectively, met standard in the math assessment. As indicator 4.3.1 displays, those results are below the Washington average and mark no improvement in the three years that test have been given.

Considerably higher scores hold for the Biology assessment of 5th graders and high school students. The average, however, for the school districts in the two counties also lies below the Washington average. It raises the question whether there are enough qualified students leaving local high schools to pursue higher ed STEM degrees before returning to local STEM jobs

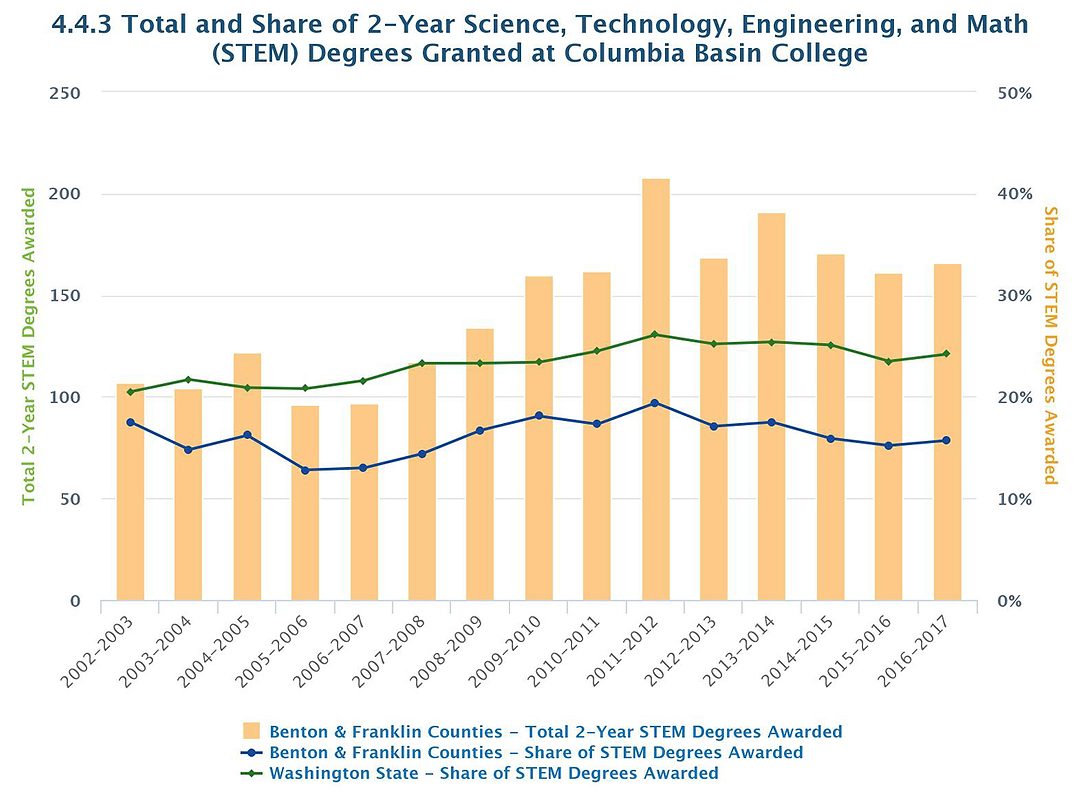

We should recognize that STEM jobs will not all be filled by those with four-year (or higher) degrees. Many will require, instead, an associate degree. How has the area fared on that score? One measure is the number of STEM associate degrees granted by Columbia Basin College. As indicator 4.4.3 shows, the number peaked in school year 2011-2012. Importantly, the STEM share of these degrees of all associate degrees granted by CBC has consistently been lower than the average of all community colleges in the state. (Note that this indicator includes nursing degrees.)

We should recognize that STEM jobs will not all be filled by those with four-year (or higher) degrees. Many will require, instead, an associate degree. How has the area fared on that score? One measure is the number of STEM associate degrees granted by Columbia Basin College. As indicator 4.4.3 shows, the number peaked in school year 2011-2012. Importantly, the STEM share of these degrees of all associate degrees granted by CBC has consistently been lower than the average of all community colleges in the state. (Note that this indicator includes nursing degrees.)

Is higher ed “degree production”, here or nearby, of local job seekers high enough to satisfy market needs? One answer comes from a monthly report of the Washington State Department of Employment Security. For the most recent available month, the occupation in highest demand in Benton County was registered nurses. In the top 25 were several STEM occupations. Ranked from highest to lowest , they were: industrial engineers, medical scientists, electrical engineers, mechanical engineers and computer support specialists. Many others were in the healthcare sector, sometimes included in STEM definitions. In Franklin County, no STEM occupations were listed, other than registered nurses, ranked second.

Aligning education “output” with local market needs is always difficult, for many reasons. It starts with the K-12 system. The offerings of higher ed then become paramount. Yet even under the best of circumstances, it is unlikely that the higher education in Tri-Cities will be able to produce enough relevant STEM degrees. Thankfully, other institutions educating STEM students aren’t too far away and should be able to help.

Patrick Jones is executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News Science & Technology

KEYWORDS september 2018