Home » Funding approved for LIGO STEM center

Funding approved for LIGO STEM center

July 15, 2019

The first detection of gravitational waves from deep space were recorded at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, out on the edge of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in September 2015 and announced in February 2016.

Ever since that announcement, people from all walks of life — many

of them students — have wanted to visit the observatory.

Many do for the public tour that happens the second Saturday of

each month — and more still via K-12 site visits and dedicated tours.

But the facility has a problem handling the large number of enthusiastic

fans.

That situation, though, will soon change.

In May, Gov. Jay Inslee signed off on the state’s 2019-21 capital

budget, which includes $7.7 million earmarked to build a STEM Exploration

Center at LIGO Hanford Observatory. (STEM stands for science, technology,

engineering and math.)

Michael Landry, the head of LIGO, is excited about the new center.

“None of the interest (in LIGO) has waned,” Landry said. “We’re

currently at 6,000 people a year visiting. We have to turn people away far more

than we’d like.”

The new facility will help bring in 10,000 visitors a year.

The catch is the earliest the new center could open is fall 2021.

“That’s subject to permitting,” Landry said. “But we’ll do

everything we can to make that date.”

The problem is LIGO is what Landry calls a “quiet site.”

“Constraints on the building come from the science,” he said.

No construction can be done while LIGO is in the middle of an

observation run, which it has been since April and will be until May 2020.

This might be easier to understand by describing what LIGO is.

It’s a large-scale physics experiment and observatory to detect

cosmic gravitational-waves, waves in space and time, as an astronomical tool.

At the time of its funding, LIGO was the largest and most ambitious project

ever funded by the National Science Foundation.

The facility, which uses lasers to detect changes in the relative

length of the 2.5-mile, L-shaped arms, and thus gravitational waves, has a

sister facility in Louisiana.

Together, those two facilities, in conjunction with the Virgo

detector in Italy, confirm when a gravitational wave actually takes place.

The instrumentation is so sensitive that a truck driving by can

set it off.

So all three facilities must confirm the same thing.

Landry said the first observatory run in

2015-16 was for four months. The second run in 2016-17 was for nine months.

This newest run already has been successful.

“We’re getting a potential gravitational wave signal more often

than once per week,” Landry said.

In fact, not a week after the third run began in April, the New

Science website reported LIGO and Virgo had already spotted a pair of black

holes colliding about 5 billion light years away.

“This third observation run, we’re excited,” Landry said. “The

next down time will be for 1½ years.”

Landry hopes all the permitting will be in place when that time

comes and that the bids for the architect and construction company will have

been accepted.

Landry said there were plenty of center supporters.

He mentions former 8th District state Rep. Larry Haler, who

learned about the potential facility in 2015.

“In 2018, we received $411,000 for a conceptual design,” Landry

said. “Larry Haler helped get the funds for that.”

Others who were of tremendous help were state Sen. Sharon Brown, and

8th District Reps. Brad Klippert and Matt Boehnke.

In addition, Rai Weiss, LIGO founder and co-recipient of a 2017

Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of gravitational waves, spoke to state

legislators in Olympia earlier this year about creating the exploration center.

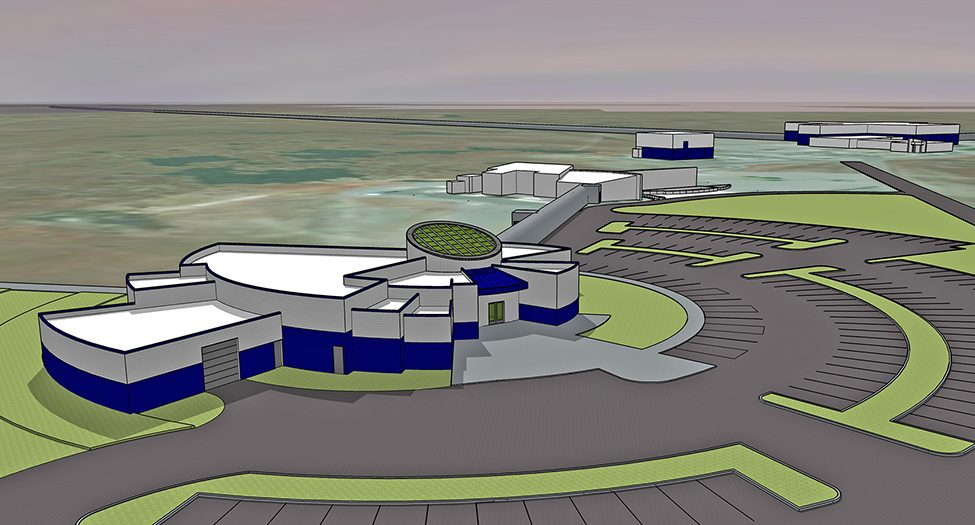

Terence L. Thornhill Architect of Pasco created the conceptual

rendering.

“It’s beautiful,” Landry said. “The purpose

of it is to really house the 5,000-square-foot exhibition space. It’ll

primarily be for K through 12 students, the general public, and universities

and colleges.”

The hope is not only to help young people think about being

scientific but to help them come up with ideas behind critical thinking and

evaluation.

“The exhibit hall, it’s not a museum,” Landry said. “It’s a hands-on

facility, for playing and teaching, so ideas will be infused in them.”

Landry says the sister Louisiana facility has 50 exhibits.

“We have a sense of some exhibits (we’ll use),” he said. “Another

element to the center is the tour interaction, and the time in the central

room. People are invited into the control room.”

During the second Saturday of the month public tours, Landry said

kids and the public ask scientists in the control room questions, and they are

answered right then and there.

Landry is amazed at the interest from far and wide.

“I had a gentleman who flew in from Japan just for this tour,”

Landry said. “He took in the B Reactor tour when he was here too. We’ve all had

that type of experience. People coming from the Netherlands, Hungary, just for

this tour.”

He expects more of that.

“We’re highly excited,” Landry said. “The universe is awash in

gravitational waves.”

Local News Hospitality & Meetings

KEYWORDS july 2019