Home » More education needed to foster a Tri-City knowledge economy

More education needed to foster a Tri-City knowledge economy

October 14, 2019

By D. Patrick Jones

To what degree will the Tri-Cities participate in the knowledge economy well underway this century?

First, a quick definition: a knowledge economy is one where a large number of jobs exploit brainpower. We need to look no further than King County to see what this kind of economy looks like. In the economists’ taxonomy of jobs, where there’s a large concentration of information technology, as well as scientific, professional and technical jobs, there’s a good chance that the local economy is knowledge-based.

D. Patrick Jones,

D. Patrick Jones,

Why does that matter? One reason lies in a strong and positive correlation between educational attainment and salaries. There are many other benefits, such as a greater defense to artificial intelligence’s implications for job destruction. Higher salaries, of course, lead to higher incomes, which bring all sorts of benefits—from retail sales, to real estate, to local government revenue. Consider King County’s annual wages: in 2018, it averaged a little more than $88,000. That’s more than $22,000 than the state average.

A knowledge economy rests, well, on knowledge. If the Tri-Cities is to succeed in developing more of a knowledge economy—now minimal outside of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory—my hunch is that there’s a strong desire to grow local talent. Typically, that talent is acquired at schools. How is talent acquisition doing here?

One has to start with the K-12 system, even though a high school diploma hardly gets anyone in the knowledge economy door. By one metric, high school graduation rates, which we can observe in the Benton-Franklin Trends data, some modest improvement can be celebrated. The extended rate is appropriate to consider in communities with a large number of English-language learners. Since the 2010-11 school year, the rate has increased by nearly 7 percentage points, with the most recent value at approximately 81 percent. Note, however, that success in the past several years has been stagnant. And also note that the local rate—averaged over all districts in the two counties—is still below the Washington average.

How about actual knowledge? If graduation rates capture the educational outcome of quantity, assessments reflect quality. As any parent of a public school student knows, the current tool to do this in Washington state is the Smarter Balanced Assessment, or SBA. It is a much more difficult test than the prior state test, the Washington Assessment of Student Learning, or WASL, but aligns with the national effort around Common Core standards. Benton-Franklin Trends depicts three assessments, each for two grades: fourth and tenth and above.

Consider the English language arts assessment. For the fourth-grade, some progress is observable; most recently, about half of the area’s fourth-graders are meeting standard. But the share throughout the state has been considerably higher. Due to changes in the test administration by the state, only one observation is available for tenth grade. But that shows the area’s tenth-graders lagging the Washington average by several percentage points.

What about math, key to the science, technology, engineering and math disciplines, powering the growth of the knowledge economy? For fourth grade, Trends data reveals no progress in meeting standard over the past four years. And area schools lag the state fourth grade average by about 10 percentage points. Less than a third of area tenth-graders were able to meet the SBA math standards, and the gap to the state is similarly around 10 percentage points.

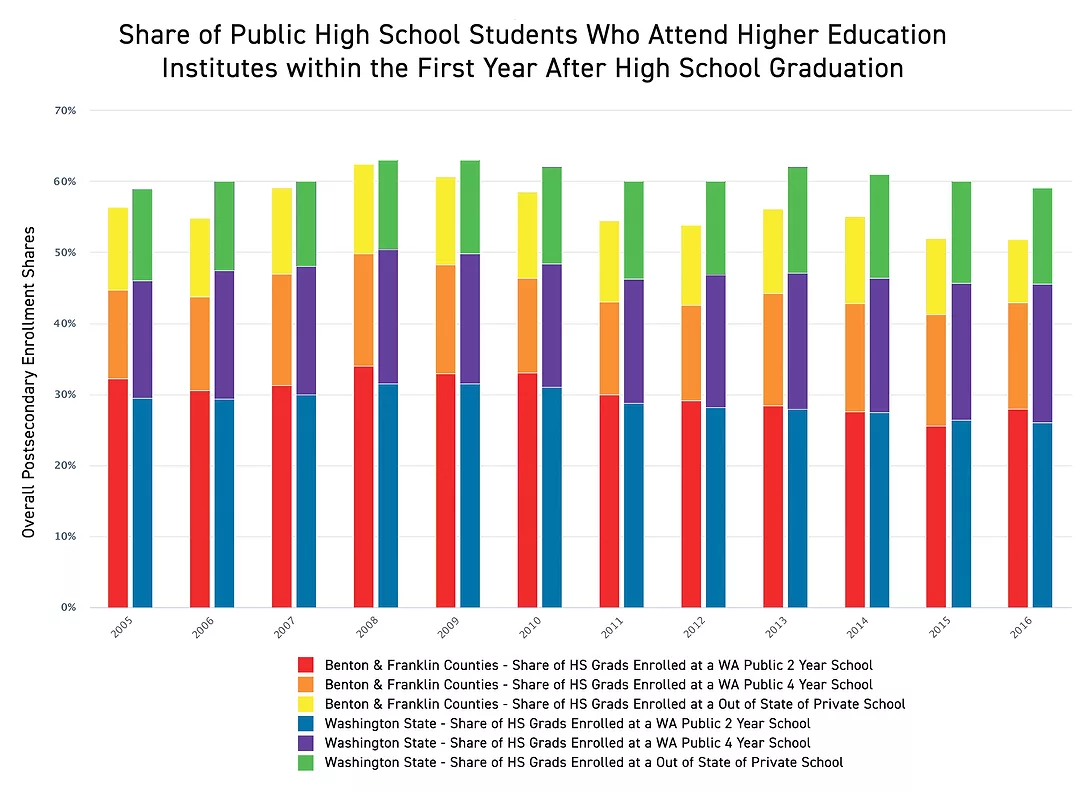

With this K-12 backdrop, it is not surprising that local college-going behavior lags its benchmarks. Consider the metric of share of high school seniors in a two- or four-year college in the year after graduation, found in the Trends data. The trend has gone in the wrong direction.

Compared to 2005, fewer area public high school grads are attending either a community college or a private four-year college or university.

The one category that has gained a bit over time is the share of students attending public four-year universities. While the trend for the entire state has been one of decline, local college-going still lags behind the state average. The one exception is community-college-going behavior: It has been and still is higher than the state.

Related Trends data—the share of adults enrolled in higher education—tells a similar story. Here the activities of area students have been and continue to be lower than for both the state and the U.S. On a bright note, recently that gap has narrowed a bit.

Where then might a knowledge economy in the Tri-Cities be within a decade? It appears to this observer that new firms will need to emerge, unless PNNL doubles its headcount. Beyond talent, other factors come into play in firm creation: the appetite for entrepreneurship, the presence of early-stage financing and an ecosystem of related firms. But the need for talent will remain paramount. Let’s hope that both the K-12 and higher ed trends over the next few years will look a little different.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News Education & Training

KEYWORDS october 2019