Home » Apollo teams with LIGO to upgrade technology that proves Einstein right

Apollo teams with LIGO to upgrade technology that proves Einstein right

April 14, 2016

On Sept. 14, 2015, Scientists at Hanford’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) proved that Einstein was correct.

The scientists detected gravitational waves—ripples in the fabric of space and time.

“That was one of the geniuses of Einstein,” said Mike Landry, LIGO detection lead scientist. “He proposed that space could have these properties—that the medium of space could vibrate.”

For decades, scientists have explored Einstein’s theory of relativity using the latest in technological advances. In the 1990s, the U.S. National Science Foundation provided funding for two LIGO Observatories—one at Hanford and one in Livingston, La.—to help physicists and astrophysicists understand the properties and phenomena that generate gravitational waves.

Apollo Mechanical in Kennewick landed the contract to fabricate and install the mechanical systems, as well as install the LIGO tool infrastructure and began work in 1997.

“At the same time, they were building the same facility in Louisiana,” said Jim Morgan, Apollo project manager. “So when we completed the installation here at the Hanford site, they sent part of our crew down to Louisiana to assist there.”

This highly specialized job included setting up the interferometers, which are the “arms” of the observatories.

“We had to line them up so they were perfect and they took it from there,” Morgan said.

Scientists at both LIGO Observatories work in collaboration with research centers located at Caltech and MIT. Together, the four distinct facilities were able to detect gravitational waves produced during the final fraction of a second of the merger of two black holes—something that has been predicted, but never observed.

Each of the observatory’s arms measure 2.5 miles long, but when the black holes collided, the arm length changed, said Landry.

“Think of the Mona Lisa,” he said. “Paint lives in the medium of the canvas, and the canvas supports the paint. If I take the canvas and stretch it, Mona gets shorter and wider, or taller and thinner. I could oscillate that back and forth and the paint goes along for the ride.”

In the case of gravitational waves, we live in the medium that is space and time, he said.

“So when a gravitational wave goes by, the medium changes,” he explained.

The change is so small that it’s undetectable without today’s advanced technology. Landry equates it to a 1/1000th the size of a proton.

“Which is why it’s no wonder these waves are hard to find and people have been looking for them since the 1960s,” Landry said.

But it wasn’t the original equipment that helped LIGO scientists detected the gravitational waves.

“In our original proposal (to the NSF) in the 1980s, we said we would probably need Advanced LIGO to find things,” said Landry.

From 2010 to 2014, the observatories were shut down for an upgrade, and once again, Apollo landed the role.

“They put out a proposal and we bid it, and it was to supply labor to support their scientific crew to do this upgrade,” said Morgan. “It entailed taking the whole electronic and metering portions apart. They had modernized parts to make [the detection equipment] more sensitive.”

Apollo Mechanical performed the upgrade with the same crew that worked on the initial LIGO project.

“We actually found our marks from 1997 and were able to line everything back in for the retrofit,” said Morgan.

Apollo had full-time crews on site for the duration of the upgrade.

The company’s CEO, Bruce Ratchford, said employees underwent highly specialized training on the LIGO systems to prepare for the project.

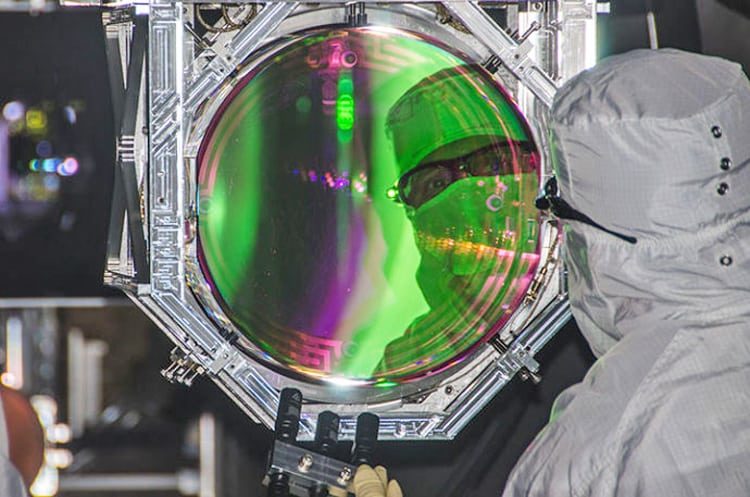

“This was some of the most difficult work in the construction business,” said Ratchford. “Full clean-room fabrication, guys in full-body clean suits — very tough — and we are very proud to be part of this historic project.”

The Apollo Mechanical team also handled the simultaneous upgrade in Louisiana, and in 2015, the LIGO Observatories were back up and running.

“The idea behind the upgrade is you would make the detector of factor 10 quieter,” said Landry. “A factor of 10 quieter noise gets you a factor of 10 times further into space. Two neutron stars merging is something we expected to see. The first detection we made was a big surprise—a binary black hole merging into another black hole.”

Just like the initial LIGO tests that ran from 2000 to 2010, scientists did several project runs with increasing sensitivity. And it’s in the continued progression and fine-tuning of equipment to see into that space that discoveries are made. Since the new components are still being fine tuned, Landry expects detection to only improve from here.

“We’re going to discover more and more regularly. We’ll see multiple mergers in our next observation,” he said.

In February, following the announcement of the detection of gravitational waves, India approved the construction of a third LIGO interferometer. It’s unclear when construction will begin, but LIGO scientists have made dozens of trips to India and said it’s possible for LIGO-India to go online by 2023.

Whether Apollo Mechanical works on the third LIGO location or not, Ratchford said they’re extremely happy for the scientists and support staff responsible for the discovery, and that the breakthrough highlights the fact that the Tri-Cities is a major hub of research and technology.

For more information about Apollo Mechanical visit .www.apollomech.com. For information about LIGO, go to www.ligo.caltech.edu/WA.

Local News Manufacturing

KEYWORDS april 2016