Home » COVID-19 brings daunting challenge to Tri-City economy

COVID-19 brings daunting challenge to Tri-City economy

May 15, 2020

An oft-used description of economics has been the “dismal science.” Most of us economists soundly dislike that nickname. After all, recent Nobel prize winners in economics have been rewarded for their insights into poverty alleviation (2019) and technological change (2018).

But this month, I present some definitely dismal numbers.

In a departure from prior columns, there is no graph from Benton-Franklin Trends.

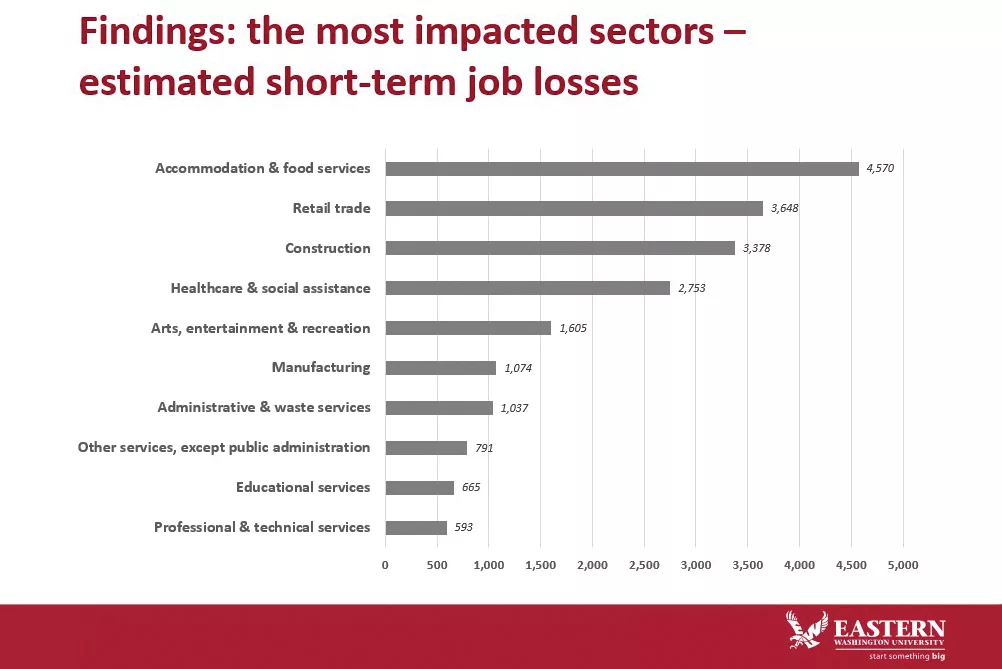

Instead, the numbers and graph will draw from a recent analysis I’ve done on the likely extent of job losses in the two counties through the beginning of May in the wake of state-mandated shutdown orders to slow the spread of the coronavirus and the deadly COVID-19 disease.

I looked at those jobs in the greater Tri-Cities that are part of the traditional unemployment insurance pool and have been, in the short-term, lost.

The analysis was done on an industry basis, looking at about 100 separate industries in the two counties.

The governor’s “essential businesses” list provided the basis for the estimate of job losses. Those government-driven losses were then supplemented by my reading of market conditions, by the ability of firms to work remotely and by data on initial claims for unemployment insurance released by the Washington Department of Employment Security.

My projections point to a job loss by the end of April slightly more than 22,000.

As a share of the workforce registered in the unemployment system, that’s 18 percent. That’s more than one out of every six workers unemployed at the beginning of May.

The Tri-Cities hasn’t experienced this high a percentage since the Great Depression.

The graph depicts what sectors have contributed the most to the total.

Clearly, the hospitality sector (restaurants, bars, cafes, caterers, hotels and motels) leads the tally. This should come as no surprise.

Any industry that relies on face-to-face encounters with customers has been severely challenged by the pandemic. As everyone knows, travel has screeched to a halt, by government decree and consumer choice.

No one should be surprised retail recorded the second-highest estimated losses.

By decree as well as customer choice, most stores remain shut.

Moderating the decline are grocery stores, big box stores that also sell food, and drugstores.

My analysis assumes that these categories have been hiring. Additionally, to the extent that the Tri-Cities has (some) employment in “electronic retail,” total sector job losses have been softened.

Construction is third for estimated job losses.

This covers three subsectors—general contractors, heavy construction (roads and physical infrastructure), and the specialty building trades.

This is relatively large sector (ranked 8th) with a high percentage of jobs shut out by state order. By the time of this issue’s publication that order lifting restrictions will be in place and a good portion of the trades should be back at work.

Health care and social assistance had the fourth highest job losses, which might come as a surprise.

One would think that the pandemic has called for an “all hands-on-deck” response from every corner of this large sector. This has not been the case for those practicing ambulatory medicine —that is outside of a hospital.

Many specialty offices that depend on hospitals for access to a significant part of their services simply have not been able to access the facilities. Most dentistry offices have been shuttered by state decree.

The large subsector of social assistance covers primarily child and youth service organizations, as well as day care sites. Many of these organizations have had to shut down.

On a relative basis, the greater Tri-City economy hasn’t been as ravaged as other Eastern Washington metro areas. I forecast a 23 percent decline in jobs in Spokane. The Tri-Cities can thank the large presence of agriculture, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the Hanford cleanup work—all on the essential services list—for that.

Where does the local economy go from here?

In a future column, I will explore the impact of relaxing employment rules for certain industries.

For now, expect unemployment numbers to get worse before they get better.

That’s largely because the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act sends unemployment benefits to thousands of workers who haven’t before qualified for traditional benefits—sole proprietors, independent contractors and workers with low earnings.

In 2017, the Census counted about 12,750 sole proprietors in the two counties. Not all will have applied for benefits under the CARES Act, but many will.

How soon these tens of thousands of unemployed in the greater Tri-Cities get back to work depends on, in Dr. Anthony Fauci’s terms, “the virus.”

In particular, when the virus faces powerful therapeutics and a vaccine. Until then, the economy will not be firing on all cylinders.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News

KEYWORDS may 2020