Home » Tri-City preschool attendance lags compared to state, U.S.

Tri-City preschool attendance lags compared to state, U.S.

September 14, 2020

The new school year has begun. Usually, this is a happy time, as it marks another beginning for students and their families. Obviously, this school start heralds a huge departure from the usual.

The pandemic’s implications — whether our children will be safe, whether they might become carriers, whether they’ll be able to study remotely — are daunting. Although not a back-to-school concern, per se, the accommodation of preschoolers looms large as well. It has since the start of the pandemic and brings up short- and long-term questions

As the pandemic spread, many child care centers were forced to reduce capacity, limit hours or even shut down. The implications for children and parents are many, not to mention those for the owners and operators of centers. A challenge pre-Covid-19 was and continues to be capacity. The data isn’t available to summarize the number of slots in Benton and Franklin counties. But it is likely that current slots are fewer than in January of this year.

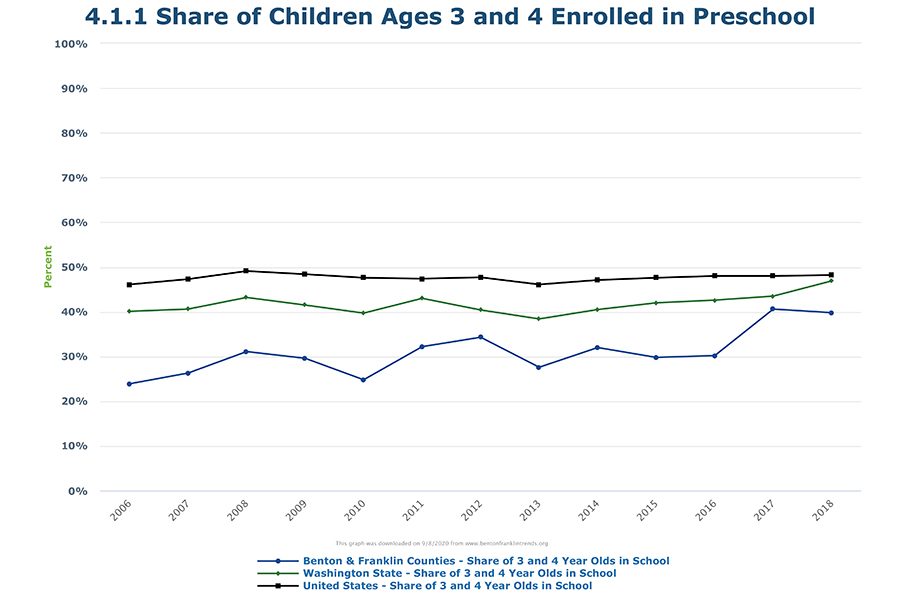

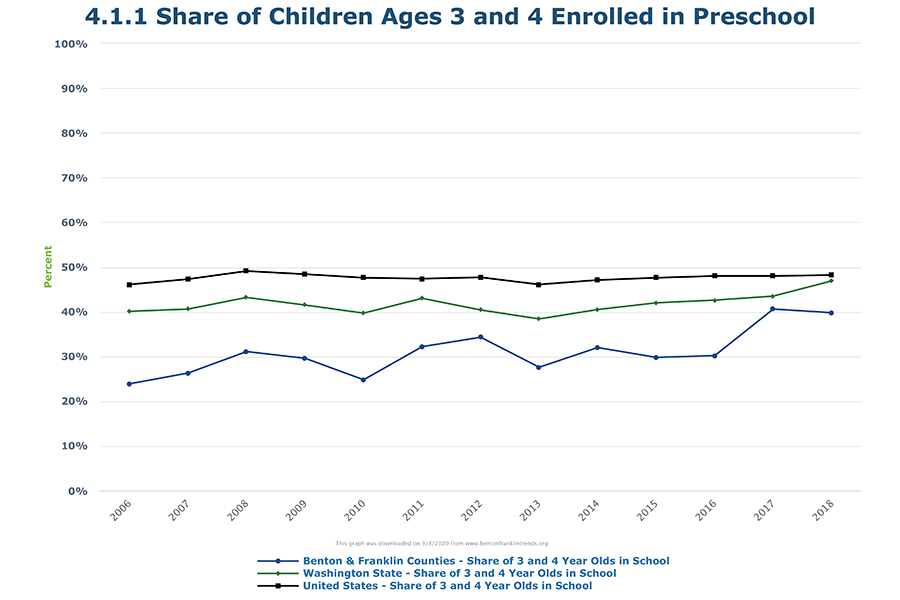

Benton Franklin Trends features an indicator that sheds some light on the usage of child care here. The accompanying graph shows that the share of 3- and 4-year-olds who attend preschool has consistently been below the state and the U.S. figures.

For the most recently reported year, 2018, about 40% of children this age attended a preschool, compared to 47% for Washington and 48% for the U.S.

Still, the trend has been moving in the right direction. Nearly 15 years ago, only 23% of this age group was enrolled. It will be a while — about a year — before the estimates for 2020 are released. My hunch is the share in the metro area will show a drop, as will its state and country counterparts.

A second pandemic challenge is the ability of parents to afford child care. While providers try to keep the costs down, it is a people business and one now affected by the increases in the state’s minimum wage. Most young families have incomes below the median, and preschool costs can amount to significant share of family income.

Economists at the OECD, an organization providing data and analysis for 26 developed countries, including the U.S., published a survey of gross costs of care, as a share of the average annual wage, in 2017.

Specifically, the economists measured the share for two children, ages 2 to 3, attending a child care center full time. The U.S. ranked slightly above the OECD average, at 31%. Canada’s share was a bit higher, but the country showing the highest share of wages taken up by child care was Switzerland, at 70%. Most of the European Union countries showed shares lower than the OECD average, notably Germany at 10% and the Nordic countries even lower.

The comparison becomes more interesting, however, when government policies are factored in.

As some may know, most OECD countries subsidize child care in one form or another. Those policies reduce the share of the average annual wage taken up by child care costs. Net costs for the OECD countries overall drop from about 28% to 15%. Switzerland’s share drops by over half and Germany and the Nordic countries decline a few percentage points. Yet the net share of the U.S. barely budges.

How is this discussion connected to an economic recovery from the pandemic?

For low-income parents who hold jobs that require out-of-home work, very much so. Child care may not be an option for their preschoolers. Consequently, leaving a job may be the likely course of action. Middle- to upper-income parents might be able to work from home or at least afford a preschool.

The health of preschool centers likely will have long-term implications for the workforce. If families cannot afford preschool, then participation in the labor force, especially by women, will decline.

In fact, it was the entrance into the labor market of millions of women in the 1980s that boosted the size of the labor force, and consequently, U.S. economic performance. And if workforce, both quality and quantity, is a driving factor for business expansion or attraction, the metro area will be at a disadvantage, relative to those communities where child care is more widely used.

The very long-term and likely most significant effects of inadequate child care rest with the child itself. Numerous studies, including those of Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman, have underscored the critical role played by early childhood learning and development. For sure, some families are able to impart these skills at home, but many parents simply don’t have the background or resources to carry out homeschooling.

So finding solutions to adequate and affordable child care will cast ripples that will continue for many, many years. Is the current share of 40% of preschool children adequate? I’ll leave that to community discussion. For now, let’s hope that the pandemic hasn’t stopped preschool-going by too much.

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News

KEYWORDS september 2020