Home » Tri-City groups scramble to offer child care to working parents

Tri-City groups scramble to offer child care to working parents

September 15, 2020

Steve Howland didn’t ask his employees at YMCA of the Greater Tri-Cities how they unwound at the end of the first week of school. But he suspects it was with a big sigh of relief.

The 2020-21 school year started Sept. 1 in the Tri-Cities with most students connecting through Chromebooks instead of attending in person.

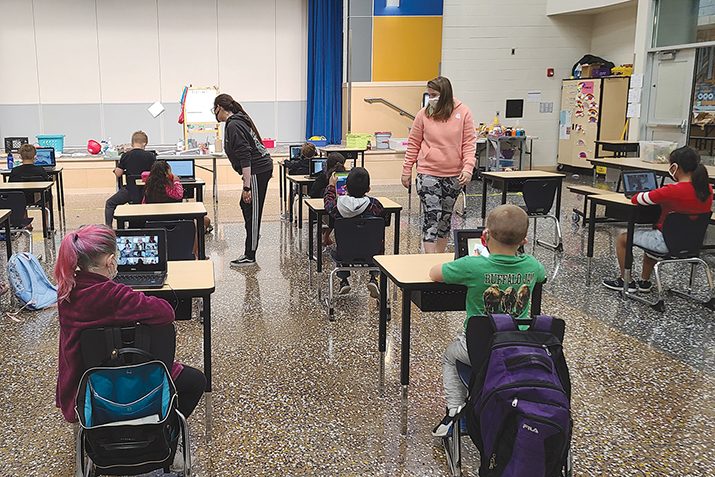

YMCA teamed with the Kennewick School District to care for a small number of students in four elementary cafeterias – Amon Creek, Fuerza, Southgate and Canyon View.

About 150 are enrolled. Three sites are full, and one has a few remaining spots.

The program runs from 6:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. and overlaps with Kennewick’s in-person services for students who struggled last spring. Not all YMCA students spend the entire day at school but many attend virtual school from their YMCA cafeteria clubhouses.

YMCA staff walked their charges through all the headaches of the first days of school – finding their school packets, navigating computer logins, internet issues and following teachers online in cafeterias equipped with student desks.

“Right now, the word ‘chaos’ comes to mind,” Howland said. “I have a lot of respect for my front-line staff. How do you help a kindergartner who has never been online?”

One week into the school year is too soon to measure the impact the pandemic is having on not only students, but working parents and their employers.

But the outlook is worrisome.

Many workers with children, particularly women, will leave their jobs because they don’t have good child care options, according to a report commissioned by the Washington’s Child Care Collaborative Task Force and co-chaired by Amy Anderson, government affairs director for the Association of Washington Business.

The report was released in late August and is posted at bit.ly/WashingtonChildCareReport2020.

Its key finding: Access to child care will drive the economic recovery.

According to the study, 61% of young children in Washington live with parents who work but there is only capacity to serve 41% of them. Even before the pandemic, more than 500,000 did not have access to licensed child care.

The department followed it up by awarding grants totaling $1.4 million to nonprofits to expand child care around the state. None are in the Tri-Cities, but there will be additional rounds.

In short, the pandemic upended everything.

Howland said the YMCA scrambled to put together a program to help working parents through the crisis.

“It’s been tough to figure out the needs,” he said. “Parents have to think about sending kids to a group setting. Right now, that’s a challenge for a lot of parents.”

The YMCA shut down for two days early in the pandemic after an employee was exposed to the virus outside of work. Howland considers the organization fortunate it wasn’t worse and notes it follows health guidelines to prevent further spread.

Local employers are responding.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is rolling out resources to help parents – and their managers – during the pandemic. It won’t discuss specifics until they’ve been shared with staff, but the goal is to supply flexibility.

“We know this is a difficult time for staff who have children in school and have virtual learners at home. The challenges come in many shapes and sizes ranging from household technology issues to single parents and dual working-parent situations,” said Jim Blount, deputy director for human resources, in response to a Journal of Business inquiry about how virtual learning is affecting operations.

About 1,200 staff work on campus most weekdays, with the balance of its 4,100 Tri-City workers working remotely.

August unemployment rates weren’t released in time for this story, but they have been well above average since April, after Gov. Jay Inslee’s Stay Home, Stay Healthy order took effect.

It reached nearly 11% in July, twice the pre-pandemic level of March. It crested at 13.5% in April and has hovered around 10% ever since.

The back-to-school chaos could be blunted by the number of people still working from home as Benton and Franklin counties linger in a modified version of Phase 1 of Washington’s Safe Start program.

That’s the most restrictive and reflects infection rates that are still above the goal for curtailing the spread of the virus.

Ajsa Suljic, regional labor economist for the Washington Employment Security Department, said the YMCA and other entities are providing a needed outlet for struggling parents. But the impact is limited.

“It depends on how resourceful families are and if they’re able to afford nanny care or outside or YMCA services,” she said. “I know not everybody can do that. There are families who are struggling.”

Even when care is available, not all parents are worried.

A spring survey by Care.com, an online service catering to nannies, home health aides and other in-home workers, found 63% of families were “uncomfortable” with the idea of placing children in day care even as states reopened.

Hiring a nanny, which is allowed under Washington’s coronavirus rules, is cost prohibitive to most.

The average cost to hire a nanny for two preschool aged children in the Tri-Cities topped $600 a week, according to Care.com.

Here are some of the other options available to local parents:

- Kennewick Parks and Recreation and Skyhawks are offering Fall Day Camp for the children ages 5-12 of working parents. The camp meets during school hours and features trained staff to support children through the virtual school day. Visit KennewickRecreation.com or call 509-585-4293 for information. Financial assistance is available.

- Boys & Girls Clubs of Benton and Franklin Counties offers full-day day care at its locations in the Tri-Cities and Prosser. Clubs provide staff support to students during the virtual school day. Go to greatclubs.org/covid for details.

- The Richland School District began in-person instruction for students receiving special education services on Sept. 16. The part-time return to school was approved after Richland moved to the next phase of its Return to School Plan. Students can spend up to two days a week in school working with teachers and other staff.

Local News

KEYWORDS september 2020