Home » Food, agriculture sectors fortify Tri-City economy

Food, agriculture sectors fortify Tri-City economy

October 14, 2020

Food and agriculture lay claim to many segments of the economy of the greater Tri-Cities.

The area’s fields, orchards, vineyards and animal husbandry operations yield a cornucopia of products. While a good portion of these products is shipped beyond county lines, much is sent to facilities here to process the bounty. Think of vegetable, especially potato, processors. Think of wineries. Think of dairies.

Of course, food also ends up on the tables of residents in the two counties, either at home or in restaurants. With a rapidly growing population, this is not an insignificant activity. Let’s take up these dimensions of food and agriculture in southeastern Washington in turn.

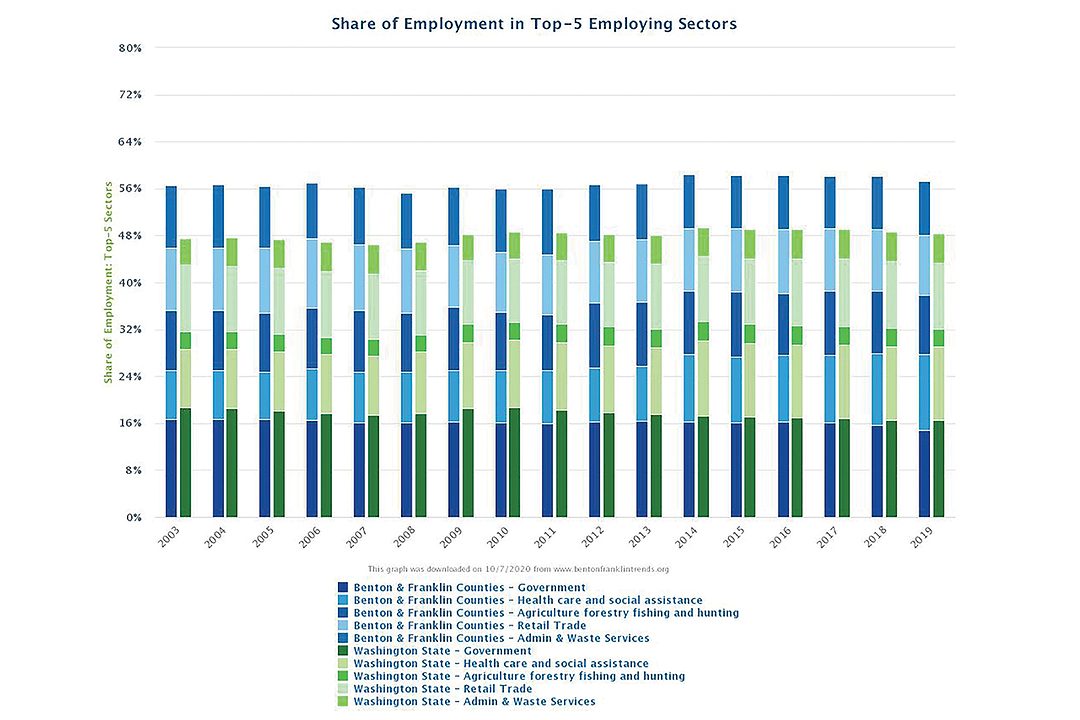

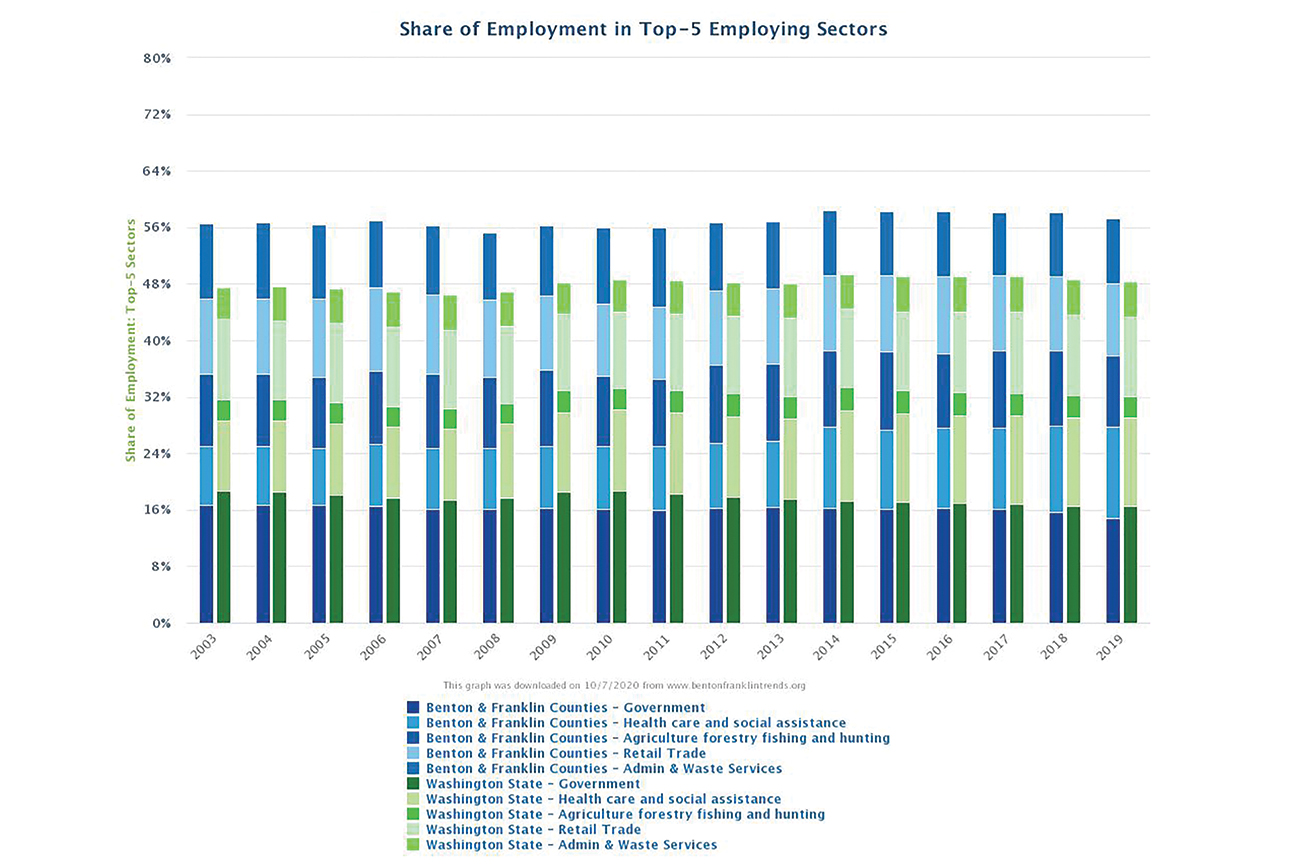

Benton-Franklin Trends carries many measures of food production at the grower level in its agriculture category. One is a tally of the number employed. In 2019, the average number in Benton and Franklin counties was slightly more than 12,700. As Trends data shows, the number of these workers translated into a fourth-place ranking among the largest employing sectors, behind government, health care and retail.

As the Trends chart shows, agriculture’s share is the third segment of the bar from the bottom. Since 2003, agricultural production has typically ranked third largest, with its share of all jobs in the two counties falling in the 10% to 11% range.

Ideally, we would also capture agriculture in the Trends data on gross metro product, or GMP. This is another measure of total activity of an economy, but in dollar terms; it’s the local equivalent of gross domestic product, or GDP.

Curiously, however, federal statistics have suppressed the data for this important sector in the two counties, so it is unclear whether production agriculture would be shown in Trends data tracking the five largest sectors by GMP.

My guess is that now it would not. This is largely due to insights from data on total wages paid in production agriculture.

GMP is predominantly composed of wages, salaries and benefits. Labor market data from Washington’s Employment Security Department put total wages and salaries paid in 2019 at nearly $410 million. While large, that payroll amounted to about 6% of total payroll in the two counties, placing it eighth among the 19 sectors of the economy.

A look at only farm-level activity would miss a significant contribution of the food sector to the local economy, however. Transforming raw materials into something of higher value also is known as manufacturing. And manufacturing here, while not found among the largest sectors employed over 8,300 in the two counties in 2019.

More than two-thirds of those workers were engaged in either food or beverage production. That represented about 4.6% of all workers, as the Trends labor force data reveals for 2019.

So aggregating production agricultural and food processing workforces for 2019 yields a share of 14.6%. This would place the total food production sector second largest among all sectors. Based on total wages and salaries, an aggregated agriculture production/food and beverage processing sector would rank fifth and, therefore, likely among the top five sectors by GMP.

Furthermore, from an economic development perspective, it is often useful to consider those sectors that export, at least beyond county lines, as a cut above other sectors. That is, these sectors don’t merely recycle existing dollars in the local economy but pull in new ones.

While the purest form of such externally-oriented sectors is tourism, local agriculture isn’t far behind. With a small population relative to the size of harvests and processed products, nearly all of Benton and Franklin counties’ food leaves the counties. (Of course, the greater Tri-Cities is in a unique and enviable position in that two of its other largest sectors — waste services and scientific services — also receive their revenue from beyond county borders.)

The third leg of the local food economy doesn’t export. But it still employs thousands of workers. That is the local consumption of food, whether at home or away from home.

Of the various businesses that make up the food services sector — caterers, bars, coffeehouses and, of course, restaurants — 8,900 workers were employed in 2019. In grocery stores of the two counties, another 2,200.

Roughly speaking, then, nearly 30,000 of the jobs in the greater Tri-Cities in 2019 were directly connected to food and agriculture. Out of a two-county labor force of nearly 127,000, that translates into an approximate share of 24%.

This quick survey of food and agriculture in the two counties hasn’t considered the jobs indirectly tied to its activities. Reduce these nearly 30,000 jobs by any proportion, and jobs will be lost in the many sectors that support them, such as health care, non-grocery retail, construction, finance and government.

How local food and agriculture will look in a post-Covid 19 world seems uncertain to this observer.

To what degree will automation displace labor in both production and processing? Will the export demand (internationally and nationally) for the local food product mix move away or toward the counties’ players?

Unless some major policy disruptions, such as trade wars, appear on the horizon, it is likely that change will be slow. More abrupt adjustments may occur among today’s restaurants.

In this season where over millennia humankind has shown gratitude for a bountiful harvest, let us hope that the pandemic will be kind to all players this vital sector.

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News Food & Wine

KEYWORDS october 2020