Home » LIGO gets visitor center worthy of its Nobel Prize-winning science

LIGO gets visitor center worthy of its Nobel Prize-winning science

January 14, 2021

With nearly 27 years designing homes and other buildings in the Tri-Cities under his belt, Pasco architect Terence “Tere” Thornhill is too diplomatic to call out a favorite.

They’re all his babies, said Thornhill, who believes buildings should tell the story of what is happening inside.

“I’m a believer in the evocative nature of architecture,” he said.

His vision is written in hundreds of sometimes dazzling rooflines across the community. The REACH Museum in Richland notes the story of the prehistoric Missoula Floods and the Manhattan Project that led to creation of the B Reactor.

Columbia Gardens Urban Wine & Artisan Village in Kennewick is topped by a clock tower and echoes the bucolic vineyards of its winery tenants.

But his current baby tops them all for linking mission to bricks and mortar.

Thornhill teamed with DGR Grant Construction to build the LIGO Hanford Exploration Center (LExC) in Richland on behalf of the scientific institutions behind the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory.

The team broke ground in October and is racing to complete the noisiest elements of construction before March, when LIGO begins its next observation run and background noise must be silenced as much as possible. The center itself is set to open in January 2022.

The $7.7 million visitor and education center will tell the story of how scientists first used twin laser observatories in Richland and in Livingston, Louisiana, to detect gravity waves that emanated from colliding black holes some 1.3 billion light years from earth.

The discovery was reported in 2016 and confirmed Albert Einstein’s century-old prediction that gravitational waves exist. The three key principals received the 2017 Nobel Prize for Physics.

The work is central to educating the public and students about the importance of science. The Louisiana observatory has an education center. With LExC, Richland gets one as well.

The two centers will share exhibits.

But Richland’s edition will tell the story through its very foundations and walls and roofs.

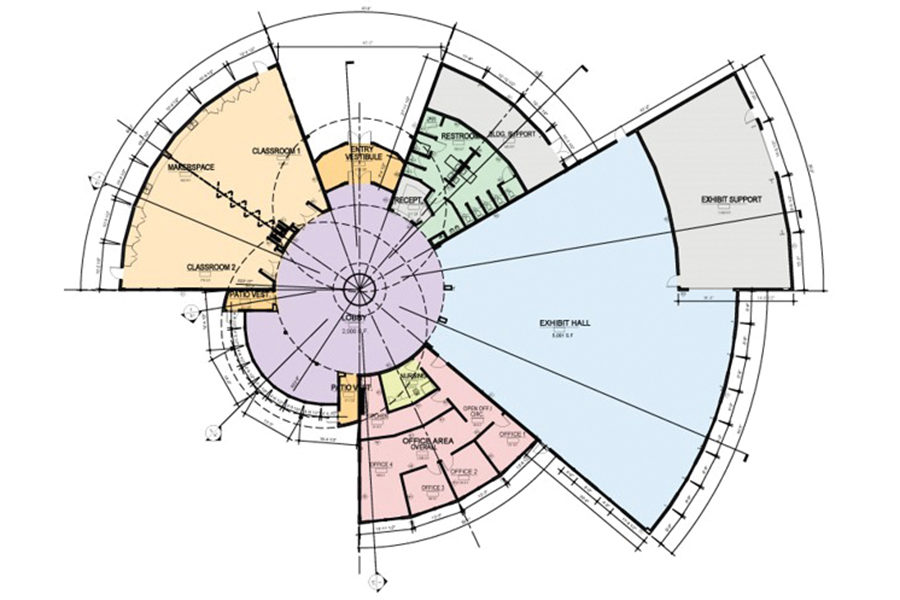

From above, LIGO LExC is a swirl of waves spiraling away from a pair of merging circles representing the first of the black holes detected. Like the black holes themselves, one is about 20% larger than the other. Both exceed our own sun in mass.

Pie-shaped wedges spiral out, a pattern that will be echoed on the carpet indoors.

The colliding black holes form a lobby, housed inside a silo topped by a dome. A replica of the Nobel Prize medal will be displayed at the center, well secured in a case.

Thornhill and DGR first pitched the black hole design in 2018 when LIGO, owned and operated by CalTech and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, asked architects with experience designing interpretive centers for ideas.

The partners had collaborated to build the REACH Museum in Richland, using the building itself to convey the Mid-Columbia’s scientific and geologic history.

Thornhill said telling the story of black holes and gravitational waves was the ultimate test of his belief that buildings should tell their own stories.

“It’s an opportunity architecturally to spread your wings,” he said. “It’s an opportunity to be creative.”

Thornhill is a confessed science “nerd,” but he is no physicist. He studied black holes and the methods scientists used to detect the gravitational waves emanating from them.

“The learning curve was pretty dramatic,” he said.

Thornhill sat down with sketch paper and a No. 2 pencil and asked himself, “How can I represent the collision of black holes frozen in time.” He laid out a footprint that captured the collision and waves.

The clients liked what they saw. Thornhill and DGR first won the competition to develop preliminary drawings and later to build, once funding was included in Washington’s capital projects budget.

The black hole concept was straightforward, but the science was not.

For example, Thornhill reached for a Fibonacci spiral – like a spiral seashell with waves narrowing at the center – to convey movement. But his scientist-clients corrected him: Waves travel in regularly spaced Archimedean spirals.

The black hole design brings the wow factor to LExC but the building is packed with other symbols.

The central silo topped by a dome that echoes telescope observatories and acknowledges that throughout history, humans studied space by looking at it, not listening to it.

LIGO altered the rules. It listened for vibrations.

“Up to this point, all the observatories were silent movies. You didn’t hear anything,” he said. “A lot of smart scientists told me about that.”

So, while the design reaches the stars, the actual construction is straightforward, thanks to state-imposed rules on the projects it funds.

LExC is designed to qualify for the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) silver rating. That means it will be exceptionally efficient from an energy and water use point of view and in the materials used in construction. It also relies on pre-engineered structural elements.

LIGO pursued the LEED designation because it values sustainability and environmental responsibility. The plaque will be located in a yet undecided but high-visibility location. Other LEED elements such as a pollinator garden, seen through tall windows in the exhibit hall, will be on full display.

The exterior materials echo the existing buildings at the LIGO campus, down to the blue stripes. Visitors will arrive at an existing auditorium and walk to the exploratory center along a path that passes through two lengths of the pipe that were not needed for construction of the laser tunnels that form the actual observatory.

LExC is expected to host 10,000 school children annually, twice the number who were able to visit the campus and its auditorium.

The center is designed to promote interest in science, technology, education and math and to answer the public’s growing interest in the work of LIGO, which stands for Laser Interferometer Gravitational Observatory.

Real Estate & Construction Local News Architecture & Engineering Hospitality & Meetings

KEYWORDS january 2021