Home » Tri-City population continues to outpace the state

Tri-City population continues to outpace the state

July 15, 2021

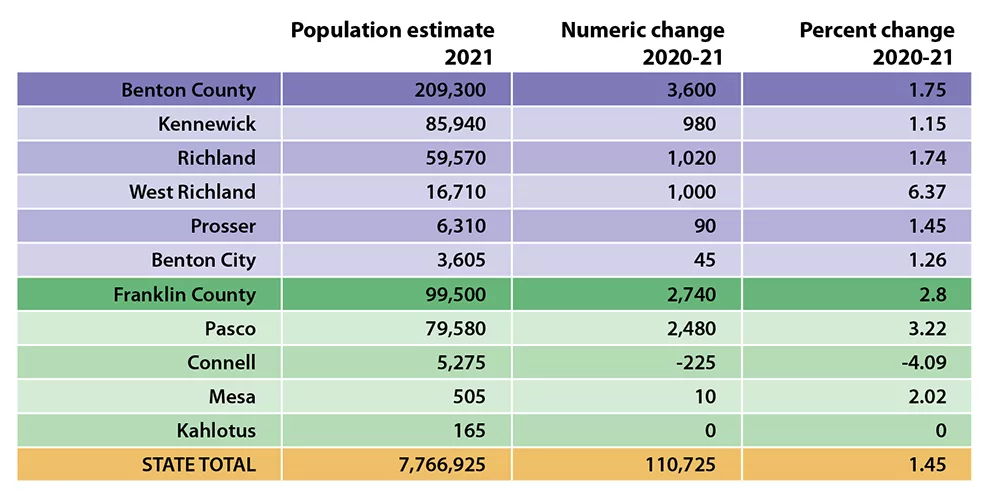

In pandemic year 2020, the population in the greater Tri-Cities grew among the fastest of all metro areas in Washington state. For Benton County, state Office of Financial Management (OFM) pegged the count at 209,300 residents; for Franklin County, at 99,500. That’s a gain of over 6,300 in 12 months.

These estimates imply year-over-year population growth in Benton County at 1.8% and Franklin County at 2.8%. Demographers at the OFM released their population estimates in late June.

This placed the two-county area third, after Clark County (Vancouver) and the greater Wenatchee area. Among all counties in the state, Franklin County’s growth rate ranked first.

Why did the numbers jump so much? Three reasons. First is the circle of life. Demographers refer to the excess of births over deaths as the “natural increase.” In the two counties, that amounted to a little over 2,000.

In-migration was the second one. It was a larger force, as it has been over the past decade. At least 2,360 people found their way to the two counties. The past five years have shown in-migration to range from 2,100 to 4,300 annually.

A third component is a bit of puzzler. It is a Census “adjustment.” The difference between OFM’s estimates and the 2020 Census count for Washington was about 49,000. This total was allocated over all 39 of Washington’s counties, according to their proportion of the 2020 estimates. For the Tri-Cities, this meant about 1,960 added to the population estimate. But OFM has not added the amount to either of the two components. It is this observer’s hunch that the majority of that increase stems from net in-migration.

What’s behind the continued interest by people from outside in the greater Tri Cities? Usually, it’s the prospect of employment. But not last year.

As Trends data reveals, the pandemic led to an unprecedented drop in jobs of over 5,500 between 2020 and 2019.

It could very well be that the greater Tri-Cities continues to expand due to its attraction to retirees. Trends data clearly shows the swelling of the 65+ ages over the past decade. In 2010, their share of total population was 10.4%. By 2020, it had grown to 14.5%.

Some evidence of the 65+ crowd’s contribution to in-migration comes from the unemployment rate. If population is growing yet jobs are diminishing, one of the few explanations is a strong in-migration of people not looking for work.

Should most of the in-migrants be job seekers, one would expect the unemployment rate to rise, relative to the state. But for 2020, this wasn’t the case. For the metro area, the 2020 unemployment rate rose from 5.6% the prior year to 8.4%, or by half. Yet the state unemployment rate doubled to 8.4% in 2020.

It is true, however, that since the start of this year, Franklin County’s unemployment rate is higher than the state average.

Monthly estimates can accessed on the Association of Washington Business Foundation website at awbinstitute.org.

Undoubtedly some in-migration took place by those whose hopes for jobs were stymied, therefore joining the local ranks of the unemployed. But it seems likely that the 65+ population continued to loom even larger in 2020.

Robust population growth brings general as well as specific consequences. From a general economic perspective, it’s hard to see too many negatives, as economic activity should climb roughly proportional with population growth. Think taxable retail sales, and hence sales tax flows to local government. Or property tax rolls.

On the other hand, rapid population growth can bring a host of challenges. One is in the housing market, especially if housing doesn’t expand in measure with population. Dramatically rising prices of residential real estate, found in Trends data, is one consequence. Of course, barriers to supply of homes matter, too.

Another challenge lies in physical infrastructure. New roads need to be built, current roads maintained and elevated demand for local government services paid for. Then there’s public K-12 schools. If enough of the population growth comes from families having children, then classrooms need to be added, leading ultimately to new schools, which of course have to be funded.

Another age-specific consequence might be the distribution of income and wealth. If in-migrants are largely well-heeled, their demand for goods and services might push up prices or access in key markets. Again, think housing. Or the ability to find a primary care physician. To this observer, however, the current mix of income and ages in the greater Tri-Cities is still a far cry from Aspen or even Coeur d’Alene.

Over the past decade, population has clipped along at an annualized growth rate of 1.5% in Benton County and 2% in Franklin County. This rate placed Benton at third among all counties in the state (behind Clark) and Franklin at the very top. Looking forward, OFM’s forecast anticipates the two counties adding about 48,000 people by 2030.

It will be fascinating to track where all these people decide to live. Will West Richland continue to lead the pack, on a percentage basis at least? Or will the more urban parts of the two counties gain in attraction, especially for the 65+ crowd?

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News

KEYWORDS july 2021