Home » She was Kamiakin High’s ‘Most Likely to Succeed.’ So, did she?

She was Kamiakin High’s ‘Most Likely to Succeed.’ So, did she?

October 14, 2021

Something about watching her dad pour over figures at night appealed to Darcy Kooiker.

The lined green paper. The mechanical pencil. The orderliness of tracking the plutonium going into weapons production at Hanford, which was her accountant father’s job.

Kooiker, then Darcy Nelson, likes it when the math is correct.

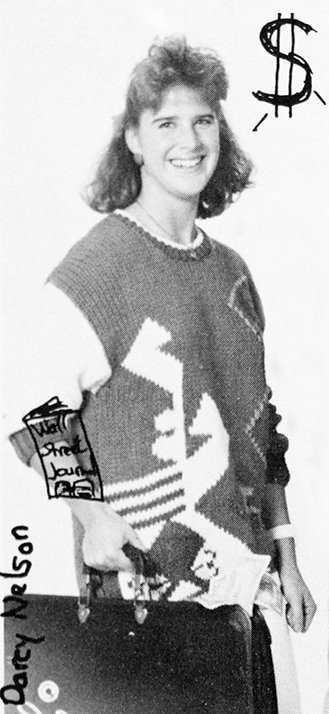

Her fellow members of the Kamiakin High School Class of 1988 agreed. They voted her one of its two “Most Likely to Succeed” graduates. She’s pictured with a classmate in the yearbook, smiling under a hand drawn bucket spilling cash. She carries a briefcase with cash sticking out.

So did she succeed? In a word, yes.

Kooiker, a certified public accountant, is among Washington state’s leading tax accountants as a working professional, as an advocate and as an educator.

She’s been a principal with national accounting firms as well as local. She advises the state Department of Revenue as a member of its Business Advisory Council. She regularly testifies before the Legislature on writing tax codes to get better compliance.

She’s taken the state to court because she believed a client was mistakenly subject to the business and occupation tax instead of the lower public utility tax. The case went to the Washington Supreme Court, which disagreed with her position. Wrongly, she maintains.

“She’s an exceptional professional,” said Tom Sulewski, CPA, chairman of the board of the Washington Society of Certified Professional Accountants. Sulewski is a shareholder at Clark Nuber PS, a Seattle-area accounting and consulting firm and was colleagues with Kooiker early in her career. He praised her commitment to clients and her work in support of the accounting industry.

Talking taxes

Talking taxes with Kooiker, pronounced “koy-i-ker,” is anything but dull.

She brings boundless enthusiasm for the subject. Her perch as a tax accountant introduced her to the myriad ways businesses earn revenue in Washington, the services and products they sell, their customers, how and where they sell it.

In her career, she’s dogged businesses that dodged their taxes, or more likely, misunderstood the confoundingly complex rules. She’s worked in private practice and is currently president of her own firm, Saltmind Consulting, though she expects to join a large firm. She raised her family on Issaquah’s Tiger Mountain and is moving to Olympia.

So, how did a Kennewick girl who was born at Kadlec Regional Medical Center become one of Washington’s go-to accountants for businesses trying to navigate state and local tax codes?

It started with that green-lined paper her father used. Her parents both live in Kennewick. She said tracking numbers appealed to her left-brain self.

After high school, she moved to Tacoma to study accounting at the University of Puget Sound. She chose the small private school after being intimidated by unruly students during a tour of the massive University of Washington campus.

UPS felt safer, though after a year, she changed her mind and became a Husky.

On-the-job training

In between classes, she held several intern-level accounting jobs. In one, she worked for a Domino’s Pizza franchise. Her employee discount made her popular with classmates.

In another, she audited Bellevue businesses to ensure they were paying the city’s version of the B&O tax on gross receipts. She went to downtown office buildings and jotted down the names of the businesses on the building directories.

Back at city hall, she checked her list against the city’s database of businesses that were paying their B&O tax bill. When she found businesses that were not in the database, they got a polite call about complying.

It was riveting stuff for a college student.

“This was nothing like what I was learning in my tax accounting class at UW,” she said.

She found the gross receipts tax interesting, even fun.

“It’s a puzzle because there are several rates and the rates are dependent on what the business does to generate revenue. We have to ask a lot of questions – what do you sell, who do you sell it to, where do you sell it?”

The internship ended when she graduated with a bachelor’s. The city of Bellevue didn’t have a job.

She had a choice of jobs. She could join the state Department of Revenue as an auditor, or go to Oklahoma and become a box executive for Weyerhaeuser, another business where she had interned.

“I just didn’t want to move to Oklahoma and be in the cardboard box business.”

In 1993, she signed on as a state auditor. She audited businesses to ensure they were paying B&O taxes and sales taxes. She would contact them, inform them of the documents needed and made arrangements to visit in person.

For Kooiker, state taxes were another puzzle to solve. She audited dentists’ offices and software companies and everything in between.

“There were small mom and pop businesses where I was sitting at their kitchen tables with their cats,” she said. “I thought it was so interesting to see what businesses do to make money.”

She recalled one sad case. A business owner was clearly skimming sales tax revenue by underreporting sales, a crime. It was also clear the business didn’t have the money to make good on its debt. Kooiker said it was a moment of clarity – she knew the owner knew she knew what was going on.

Worried for her safety, she packed up her files and finished the audit back at the office.

The owner died of a heart attack shortly after the department sent its findings.

Move to private sector

After three years in state government, she felt she had learned what she could about Washington taxes. Once again, she had a choice. She could join a national accounting firm, or sign on for a post in Microsoft Corp.’s tax office.

She chose the national firm, Price Waterhouse, figuring she’d learn more as a consultant than in a corporate role.

“I probably would be retired on an island somewhere if I had taken that position with Microsoft,” she said. “But, no regrets.”

At Price Waterhouse, she learned about taxes levied by other states. It was interesting and so too was her first experience in a large corporation. Unlike state government, where employees pay for the coffee in the office coffee maker, Price Waterhouse provided free food and sodas. She gained 15 pounds, she said.

She would change jobs several more times while starting a family. Most recently, she was a partner with Armanino LLP and prior to that, Ryan.

Son Holden arrived in 1999. Daughter Elaine followed in 2002. She took master’s level courses and worked full time.

First Student v. Washington

Her Supreme Court case stemmed from her time with Ryan, a national firm that specializes in identifying refunds.

Her understanding of state taxes helped her identify when clients mistakenly overpaid and were owed refunds. In one case, an aluminum company overpaid its B&O taxes (“because B&O is complicated.”) It should have been paying a lower rate and qualified for a refund.

A private school bus case identified what she considered a flaw in the state rules governing taxes. First Student, a private school bus operator was paying B&O taxes. But Kooiker thought that the state’s administrative rules misapplied the tax.

The law suggested a hire for carry operator should be paying the lower public utility tax.

“I researched and researched and researched and concluded that the administrative rule was wrong and that the school bus companies were due a refund,” she said.

The only way to change the language was to sue. Ryan hired a prominent law firm and made its argument in superior, appellate and state supreme court trials. It lost every time.

The Supreme Court justices concluded the term “for hire” was ambiguous and resolved the dispute in favor of the long-standing B&O interpretation. (2019, First Student v. Washington)

“That’s the one thorn in the side of my career is losing that school bus case,” she said.

This Tri-Cities Area Journal of Business feature, Tri-City Connections, is a series of occasional profiles of Tri-City natives and former Tri-Citians who have excelled in the world of business.

If you have one in mind, let us know at info@tcjournal.biz.

Local News Taxes

KEYWORDS october 2021