Home » Tri-City manufacturing sector has a distinct flavor

Tri-City manufacturing sector has a distinct flavor

June 10, 2022

Manufacturing in the two counties didn’t shine during the pandemic.

According to recent work the Institute undertook for the Port of Kennewick, the most positive employment changes during the “shutdown quarter,” Q2 of 2020, were found in the following sectors: finance and insurance, transportation and warehousing, information, wholesale trade and retail.

Yet, manufacturing didn’t lose too much luster. Ranked by employment losses in that quarter, the most unfortunate sectors in the greater Tri-Cities were: hospitality, arts and entertainment, retail, construction and agriculture.

Manufacturing’s fate ranked in the middle, showing only a modest loss of jobs.

This is not to say that manufacturing has reclaimed its pre-pandemic numbers, at least by the end of last September.

Total headcount in this sector in the two counties was still about 500 lower than in the same quarter of 2019. Then again, in the third quarter of last year, overall employment was still about 1,500 below its level in 2019.

Thankfully, by the fourth quarter of 2021, total employment in the metro area exceeded its 2019 levels. We won’t know for another few months whether manufacturing made a similar comeback.

According to the most recent full year of detailed data, 2020, manufacturing is the ninth-largest sector in the two counties, as measured by employment.

Compared to other Eastern Washington metro areas, this is a relatively low ranking.

At the top is Walla Walla, with manufacturing claiming one out of every seven jobs.

At the bottom is the greater Wenatchee area, where manufacturing holds 4.3% of the workforce. And the slice of Benton and Franklin counties’ labor market? About 6.7%.

Why should we care? Usually, manufacturing wages are among the highest in any local economy. And manufacturing usually brings positive spillover effects to other sectors of the economy.

Unlike other metro areas around Washington, local manufacturing doesn’t offer much of a wage premium.

In fact, the most recent annual manufacturing wage was about equal to the all-sector annual wage in Benton County and about 4% higher than the all-sector average in Franklin County.

Contrast these 2020 results to Grant County, with a 16% premium, or Yakima County, with its manufacturing workers enjoying a 23% premium to the general workforce.

A major difference, of course, to the neighboring counties can be found in the presence of two highly paid sectors which do not loom large in Grant and Yakima: waste management as well as scientific and professional services.

As I’ve written in other columns, local manufacturing is largely an agriculture processing affair. In the third quarter of last year, nearly half (46%) of all manufacturing firms fell into food and beverage category. Measured by employment, agricultural processing swings an even bigger bat, taking up about three quarters of all manufacturing employment.

Furthermore, manufacturing here heavily depends on the Latino/a workforce.

The most recent Census data, from the second quarter of last year, reveal that 43% of all manufacturing jobs in the two counties were filled by these workers. No other sector, not even agricultural production, shows such a preponderance of Latinos/as. (At the other end of the range, Hispanics make up only 10% of the “white collar” sector of scientific, technical and professional firms.)

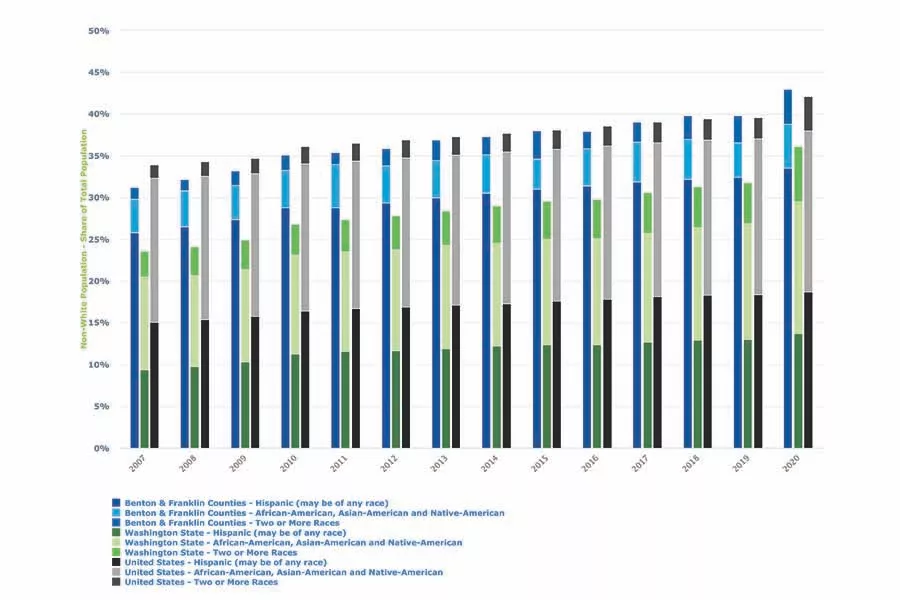

As Benton-Franklin Trends data reveals, the overall share of the population in the two counties that identifies as Latino/a is about a third. This is the dark blue segment of the graph. With a good portion of the Latino/a population not of working age, the role then played by this population in manufacturing is pronounced.

Further, despite their outsized presence in the sector, the Latino/a factory worker here earns only 73% of the average factory worker, again according to Census data from the second quarter of last year. There are several sectors in the greater Tri-Cities where pay of Hispanics is nearly at a par with the average. These are transportation and warehousing (97%), hospitality (94%) and retail (76%). And Hispanic construction wages are at 82% of overall wages. The departure from average in manufacturing likely reflects the types of occupations filled by Latinos/as.

Where might manufacturing in the greater Tri-Cities go from here? By all indicators, into deepening agricultural processing. Whether the Tri-Cities can diversify its manufacturing base remains a big question. It is undoubtedly easier to build upon a local economy’s strengths, a maxim in economic development strategies.

Yet, could more tech-based manufacturing unfold? The intellectual capital is certainly here. And there is already a presence, albeit small, of some firms that fit the description, such as chemical and electronics manufacturing. If these can expand, or if food processing can become even more efficient, allowing higher wages to be paid, then the entire economy will benefit.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Manufacturing

KEYWORDS june 2022