Home » Politics, weather and inflation put the squeeze on Washington ag

Politics, weather and inflation put the squeeze on Washington ag

June 13, 2022

Pam Lewison is of two minds when winter gives way to spring.

She’s thrilled by the sweet smell of freshly plowed fields, the green fuzz in the orchards, the newborn livestock.

She’s less thrilled by the daunting challenges facing Washington agriculture in 2022. The state’s 35,300 farms and ranches collectively raise more than 300 products.

Lewison, director of Washington Policy Center’s Initiative on Agriculture, which is based in the Tri-Cities, worries that the state Legislature has taken a “combative” stance toward agriculture.

That, along with weather, water availability, fertilizer and fuel prices, supply chain challenges, access to shipping and rising labor costs are all in sharp focus this year.

But she’s nothing if not hopeful in the spring.

“Farmers are optimists and realists. They see what is, but always hope for what can be,” said Lewison, who raises beans, field corn, alfalfa and teff, a high-protein, low-carb hay crop.

Washington farms produced $9.6 billion in 2016, according to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, the most recent complete federal assessment of the value of agriculture. The census occurs every five years.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is preparing for the 2022 Census. Operators who want to participate and don’t receive surveys from the National Agricultural Statistics Service can sign up at agcounts.usda.gov/static/get-counted.html.

The Washington Farm Bureau calculates that farm production coupled with more than $20 billion in revenue related to food processing and manufacturing translates to 12% of the state’s economy.

The Washington Department of Commerce calls it the state’s second largest manufacturing sector behind aerospace.

Lewison fears inflationary pressure on fuel and fertilizer costs coupled with increased regulation and particularly new overtime wages phasing in by 2024 will force some operators out of the industry.

“There’s a lot of pressure,” she said. “I think that we are at a point where the domino effect will occur with people making hard choices about things costing more and the dollar being worth less.”

She sees a Legislature that is out of touch with agriculture. She’s particularly worried about the riparian buffer bill, which requires trees and protection zones along creeks and rivers.

She expects it to crop up in the 2023 session. The proposal notably exempts urban but not rural areas from the rules.

“Just because we farm and live in a rural area doesn’t mean we should be the only people who bear the burden of saving fish or the environment,” she said. She called on voters to voice their support for farmers and ranchers.

Much about 2022 is still unknown, from weather to the impact of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Here are some of the highlights of what’s happening in Washington agriculture, as reported in this year’s edition of the Tri-Cities Area Journal of Business’ Focus Agriculture + Viticulture magazine.

Apples

Nothing says “Grown in Washington” more than a shiny fresh apple. The $2.2 billion industry is easily the largest in Washington ag. For 2021 and now 2022, the story is mostly about weather.

The heat dome that settled over the Pacific Northwest in June 2021 is behind a moderate drop in output, according to Todd Fryhover, president of the Washington Apple Commission. The state tallied 122 million bushels, down from its typical 130 million or so.

Fryhover said the unseasonable snow in April could lead to a similar result in 2022.

Potatoes

The first shipments of U.S. fresh potatoes entered Mexico on May 11, 2022, fulfilling a longtime campaign to open the market beyond a narrow zone along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Mexico’s Supreme Court voted to end an embargo in 2021 but the actual deliveries were slow to start. This spring, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack met with his counterpart and set a May 15 deadline.

Mexico imported $60 million in fresh potatoes in 2021. That is expected to rise to $150 million, according to the National Potato Council, which is led by Pasco farmer Jared Balcom.

“This is an important moment for the U.S. potato industry,” he said, calling Mexico a “vital market.” Balcom delves deeper into the potato industry in a column on Page 26.

Washington is second only to Idaho when it comes to growing potatoes – more than 10 billion pounds. Up to 90% of the crop is sold to processors such as Lamb Weston and turned into frozen french fries and other potato products.

Exports

There’s good news and bad for exports.

The value was up in 2021 but only because of inflation and price hikes. Shipping volumes dropped as the Northwest Seaport Alliance – the ports of Seattle and Tacoma – turned an unwelcome corner. In May 2021, more shipping containers left empty than full, thanks to the unfavorable economics of oceangoing vessels.

Prior to the pandemic, the Washington ports were evenly balanced, a point of pride, noted Melanie Stambaugh, communications director for the alliance.

In Seattle, the port has created a near-dock yard on the waterfront for ag-filled storage containers on the theory that being able to swiftly move them to oceangoing vessels will get them on their way. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is covering drop fees – $200 for regular containers, $400 for refrigerated ones. A similar effort is planned at a near-dock site in Tacoma.

The Northwest Seaport Alliance plans to report on the success of the initiative this summer.

Grapes

Washington grape growers harvested 179,600 tons of wine grapes and 103,000 tons of juice grapes in 2021. The bad news: Grapes were affected by the heat wave, which led to smaller clusters.

The good news? The weather in September and October was ideal for ripening, which led to higher quality fruit.

Smoke, which has plagued some but not all recent summers, is a rising threat to grapes and triggered the formation of a special task force to evaluate its impact on grapes and wine, and potential steps to mitigate it. A team of West Coast researchers received a federal grant of nearly $8 million to study the issue in 2021.

Cherries

Cherries were another crop heavily impacted by the late June heat dome. The notoriously fragile fruit shriveled in the 100-plus degree weather. Fortunately, much of the Washington crop had been harvested before the real heat set in, said Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association.

Cherry growers harvested more than 18.6 million 20-pound boxes of cherries in the Northwest – Washington and Oregon – in 2021.

DeVaney said labor remains a challenge in 2022, as does the unseasonable snow in April, which arrived about the same time fruit was setting in area orchards.

He said it could lead to a potential reduction, but not a wipeout, barring more unwelcome weather events before the start of the harvest, typically early to mid-June.

Wheat

Washington is the nation’s fourth largest wheat-growing state with more than 2.2 million acres in production – 1.8 million acres planted with winter varieties in the fall and the rest with spring varieties in the warm months.

Nationally, wheat is third among U.S. field crops, after corn and soybeans.

Washington exported nearly $962 million worth of wheat in 2021, a whopping 43% increase attributed to the Phase 1 trade agreement negotiated with China during the Trump administration.

Winter wheat production will rise 60% in 2022, based on

May 1 conditions, additional acreage and yields of 67 bushels per acre, up from 42 in 2021, according to USDA estimates.

Oregon and Idaho will see upticks as well, by 35% and 28%, respectively.

But drought, trade issues and input prices (fuel and fertilizer), as well as foreign competition for customers, pose long-term challenges to the region’s wheat growers.

Most Washington-grown wheat is exported. Like most other ag products, it must get onto oceangoing vessels, an ongoing challenge for ag exporters.

U.S. Wheat Associates projects exports will fall 21% in 2021-22 compared to the 2020-21 cycle, based on USDA export data.

In a May outlook, the USDA projected prices will reach a record in 2022-23 – $10.75 per bushel – thanks to tight supplies but the overall pattern is reduced production.

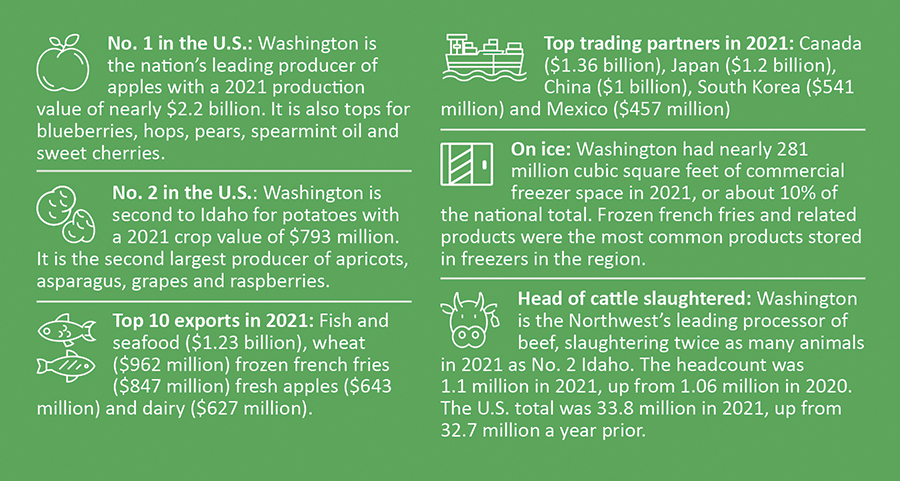

Numbers tell the story of

Washington agriculture

Washington farms and ranches produce more than 300 different crops with a combined value of about $9.6 billion – a figure that triples once food processing is factored in.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service tallied 35,300 agricultural operations in 2021. Collectively, they cultivated 14.6 million acres.

Here is a look at our agriculture by the numbers, gleaned from the USDA, the Washington Department of Agriculture and the state Office of Financial Services.

Agriculture + Viticulture

KEYWORDS june 2022