Home » Tri-City area STEM sector is both rich and poor

Tri-City area STEM sector is both rich and poor

July 13, 2022

The greater Tri-Cities is rich with STEM jobs.

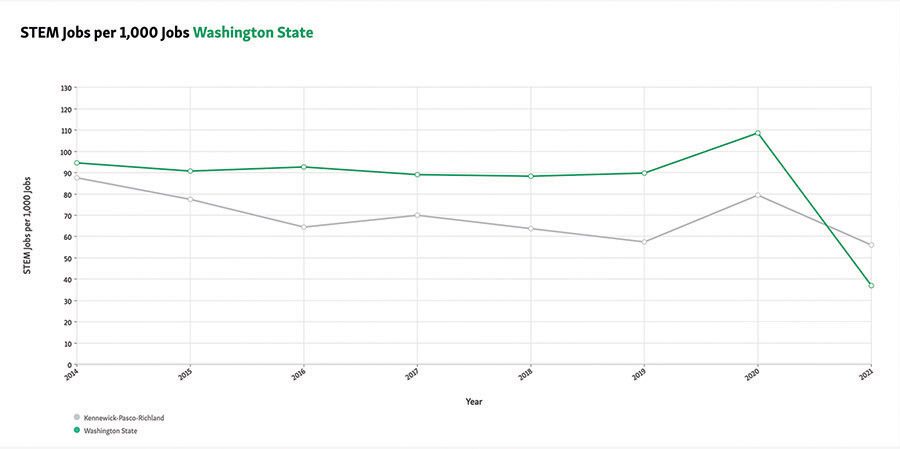

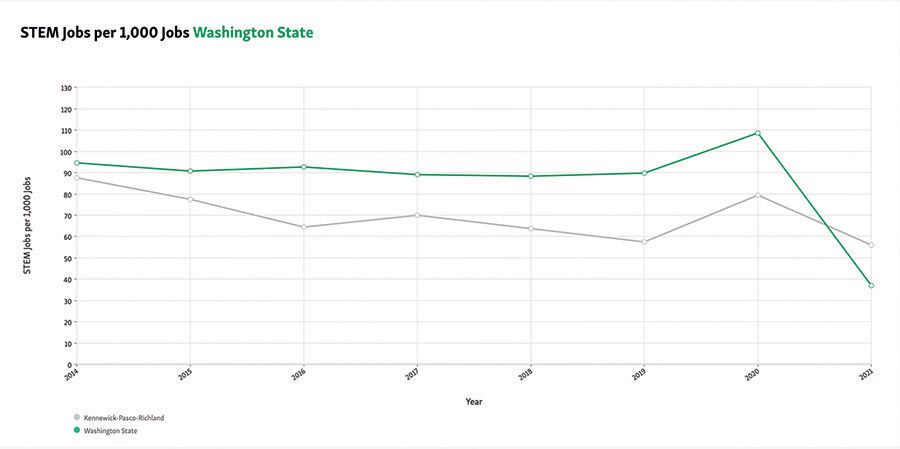

The chart, taken from the Vitals of the Association of Washington Business Institute, makes this clear.

The density of STEM jobs in 2021 in the two-county workforce was slightly over 5.6%. That places the metro area at the top of the heap for STEM jobs in the state. The next closest are the Bremerton-Silverdale and the Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro metro areas, both with densities of 3.8%.

Notions of STEM can take slightly different shapes. The Vitals adopts a STEM definition used by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The list of occupations numbers 100, and includes occupations in of computers, engineering, mathematics, life sciences and physical sciences. Notably, excluded, however, from the BLS list are all health care professions.

The STEM-richness of the local economy is largely due the outsized presence of engineers. Statewide, that general occupation made up 1.6% of the workforce in 2021. For the greater Tri-Cities, the share of engineers was nearly double, at 2.8%.

The presence of both life and physical scientists also contributes to the STEM standing of the Tri-Cities. Statewide in 2021, these professions constituted 0.6% of the workforce. Here, the share was again nearly double, at 1.1%.

The one area in which the greater Tri-Cities appears STEM-poor is information technology. Statewide, the share of the workforce engaged in computer science-related occupations was a whopping 6.2%. Here, those occupations contributed less than a quarter of that share, at 1.5%.

This quick statistical sketch of undoubtedly confirms what many readers sense about this community. We know that the high STEM standing results from the presence of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and the many facets of the Hanford cleanup. This standing is, and should be, a point of pride for the local community.

Yet, if the greater Tri-Cities labor force is STEM-rich, the composition of its companies is STEM-poor. We do not have ready definitions of science & technology companies as BLS provides for the labor force. Yet, it seems clear that, outside of PNNL and Hanford-related activities, the cup of local economy doesn’t overflow with technology companies.

The latest (2021) summary of companies from the Washington State Department of Employment Security (ESD) hints at some presence of advanced manufacturing, assuming that high average annual wages are correlated with high value-added. In the category of chemical manufacturing, for example, ESD economists show nine companies, with the average annual wage of over $104,000. Similarly, computer and electronic product manufacturing companies number eight, with an average annual wage of over $84,000.

Information technology, so critical to the high-tech profile of the state, is present here, but barely. The ESD 2021 data show no internet publishing and broadcasting, i.e. software, companies. There are, however, 10 firms that are classified as ISPs, search portals or data processors. And the pay is quite good, over $93,000 in average annual salaries.

In all, however, these likely STEM-oriented companies sum to a few dozen – out of a universe of about 9,000 firms in the two counties. And the total headcount of these companies? About 1,000, or less than 1% of the total number employed in 2021.

An unknown in this assessment lies in the composition of firms in the category of professional and technical services. ESD reports 630 companies in this sector in 2021. Often, technology companies show up in this section of employer data. But the category also includes offices of advertising, accountants, architects, design and law. For sure, the category includes engineering offices. Yet, we don’t know how much engineering firms in the greater Tri-Cities owe their existence to work outside of the Hanford complex.

It seems then to this observer that the STEM pulse – measured by firms – is weak beyond Hanford and PNNL. If true, what can be done to quicken the pulse?

Three avenues come to mind. The first concerns policies around technology transfer, in particular, the licensing arrangements that PNNL adopts for its patents. The second is the state of local entrepreneurship – are there risk-takers here who also have technology chops? The third is the depth of angel capital in the region: are there early-stage investors willing to supply at-risk dollars to technology entrepreneurs?

Each one of these factors deserves a column of its own. For the immediate future, the assessment of an economy that is STEM-rich in its occupations but STEM-poor is in its firm composition is likely to hold.

If the greater Tri-Cities is to translate its human capital wealth into a technology-rich economy, progress will need to be made on at least these barriers.

Of course, some serendipity will help.

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News Science & Technology

KEYWORDS july 2022