Home » Toxic algae testing stays local, thanks to new equipment

Toxic algae testing stays local, thanks to new equipment

July 13, 2022

By Amanda Mason

For the Tri-Cities Area Journal of Business

Toxic algae can no longer hide in plain sight.

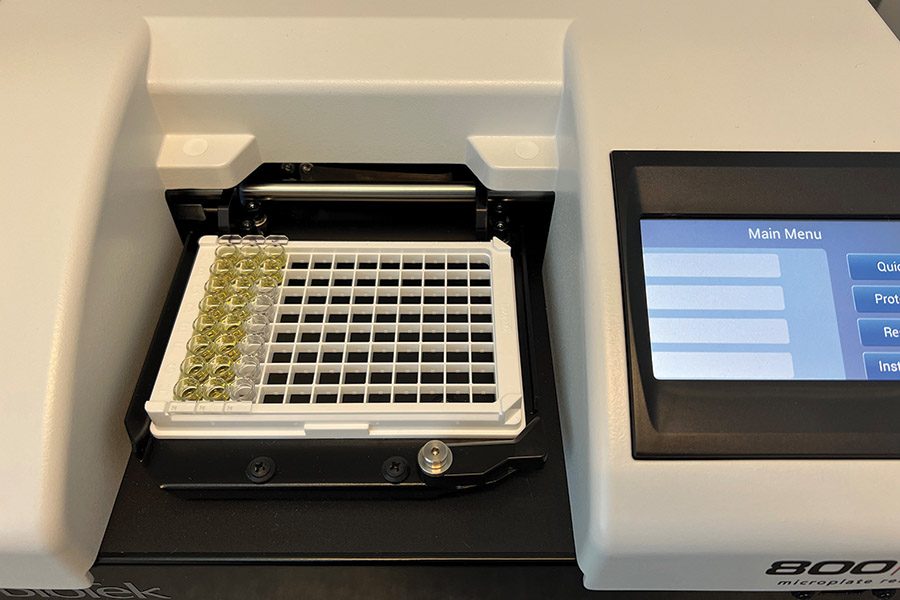

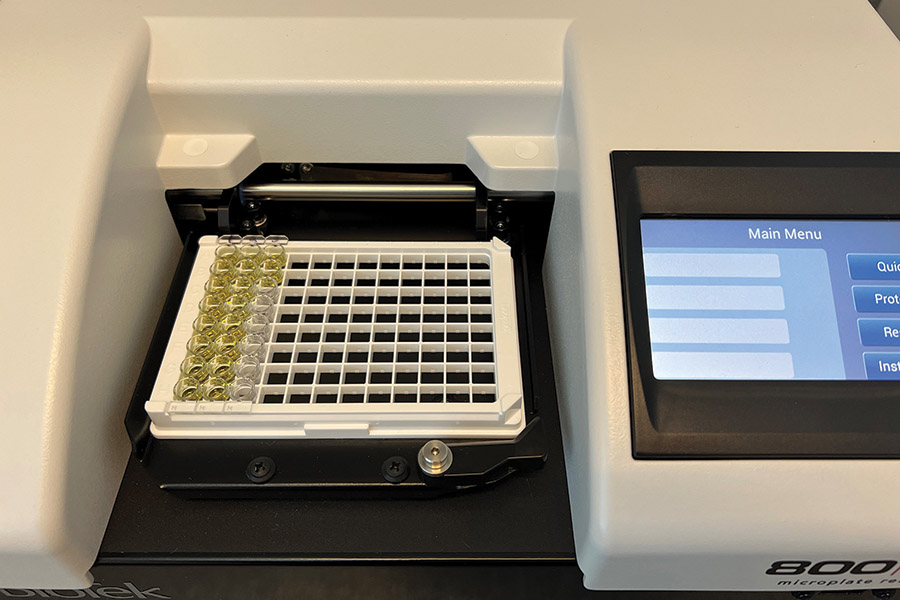

The Benton-Franklin Health District Water Lab in Kennewick is now home to ELISA, a testing kit and plate reader that detects toxins from algae blooms in water samples collected from local lakes and rivers.

The instrument gives the local health district an important new tool to detect water-borne toxins and to monitor multiple sites at a time.

“This is real science that is directly helping the public. (Toxic algae) is something that is potentially very dangerous to humans and animals. People can die from this. To be on the first line of defense detecting toxic algae is exciting,” said Jillian Legard, lab supervisor at the health district.

Fall 2021 was a challenging time for the district, which detected an unprecedented occurrence of toxins from algal blooms that had not been previously detected in the flowing waters of the Columbia River.

Several dogs lost their lives after being exposed to these blooms.

At the time, no local entity had the equipment to test, so water samples were flown to King County Environmental Lab.

“The lab was essential in assisting Benton-Franklin Health District and our cities in developing the ability to test locally. King County helped us with the push for funding and generously gave of themselves to train our lab staff,” said Rick Dawson, the health district’s senior manager for surveillance and investigation.

Dawson said that ELISA will help public health officials protect the community by maintaining a routine testing schedule of sample sites that will detect toxic algae sooner.

The ELISA system arrived in July. The test needs less than a drop of water – 50 microliters – to detect toxins. The plate reader reads color intensity to determine the level of toxins in the sample. “ELISA” refers to “enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.”

Health officials can now test samples from drinking water intakes and up to six to 10 recreational water sites at once, producing results in a day and a half.

“Even though it only takes the tiniest amount of water to test for toxins, we collect 250 milliliters (about 8.45 ounces) of water from each testing site in amber-colored jars to ensure we have enough samples to test,” Legard said.

Amber-colored jars protect samples from any light degradation.

Legard said the lab team “runs the test samples in duplicate, then we average them due to the small volumes required and the variable nature of attempting to detect molecules of toxin from a massive body of water.”

The bigger the sample, the greater the chance of collecting any toxic algae.

“It’s like if you go fishing in a lake with one pole and you don’t catch any fish all day. Does that mean there are no fish in the lake? No, of course not. There are fish in the lake; you just didn’t catch any with your one fishing pole. You are more likely to catch a fish with multiple lines or a large net,” Legard said.

This method for testing helps to minimize false negatives. The plate reader, funded through the state Department of Health, tests toxic algae.

Legard said that soon, ELISA could be used to test for other contaminants in the environment.

With summer in full swing, Dawson advises residents to enjoy the outdoors, but to be cautious.

“You can’t tell by looking at water if toxins are present or not. Look before you leap with all waters. Know that there is a risk any time we are in open water. Open water is not treated, it runs through lots of things, and many things get in the water. The best thing you can do is be aware of your surroundings and look for information about where you are. Look for signage. If toxins are detected in the water, there will be proper signs on display,” Dawson said.

Amanda Mason is communications coordinator for the Benton-Franklin Health District.

Local News Science & Technology

KEYWORDS july 2022