Home » Local hospitality has recovered by sales and wages, but not by jobs

Local hospitality has recovered by sales and wages, but not by jobs

August 11, 2022

From an economic perspective, measuring tourism is a bit dicey.

Outside of a national “experimental” account from the U.S. Department of Commerce, government statisticians don’t track a sector labeled “tourism.” That’s because economic activity related to tourism cuts across several established ones: accommodations, food and beverage, retail, transportation, and arts and entertainment.

Spending surveys typically indicate that tourists drop their money in sectors listed in the above order. That is, tourists generate the highest percentage of revenues for accommodations operators, but increasingly less so for the subsequent sectors.

Of course, this depends on the locale. Tourists make up a much larger share of sales of food and beverage establishments, retail stores and the arts in Jackson Hole than they do in Spokane.

Since Eastern Washington University doesn’t have access to a continuous survey of tourist spending in the greater Tri-Cities, the most obvious proxy consists of activity in the first two on the list: accommodations and food-and-beverage establishments.

Their totals exaggerate the amount spent by tourists, as they encompass activities not only by business travelers but by local residents. The latter effect might be slight for accommodations operators, but not for local restaurants, bars and cafes.

In the face of these admittedly substantial caveats, when can be said about recent accommodations and food services in the two counties and thereby tourism activities?

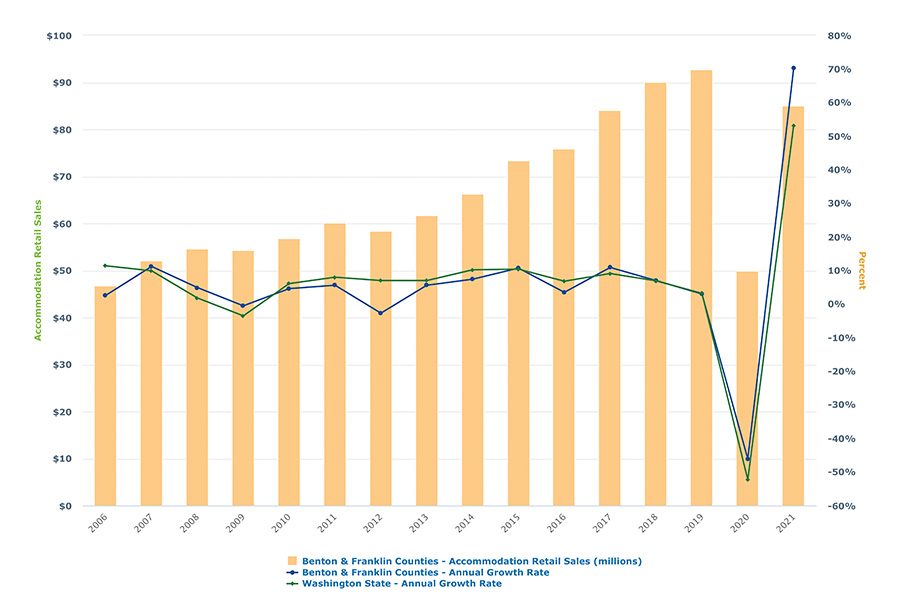

The “cleanest” measure comes from Benton-Franklin Trends data on accommodation retail sales. At about $85 million in 2021, sales by local firms in the industry rebounded from the pandemic low of $50 million in 2020. The total, however, is still below the peak reached in 2019 of $92.7 million.

A rebound in accommodations employment has been much more tepid. Total average employment in the two counties in 2021 was 889. That’s an improvement of a mere 52 workers from 2020. And the 2021 average was 165 lower (-23%) than the peak of 2019.

Combining accommodations with eating and drinking to form the hospitality sector, we arrive at a more robust rebound: 2021 brought substantial improvement over 2020, but still off from the 2019 peak, down approximately 400 jobs, or 4%.

In contrast, 2021 total average employment in the two counties was down about 1% from the 2019 peak.

Average annual earnings in hospitality services, however, tell a different story.

They jumped by nearly one third (31%) between 2017 and 2021. Across all sectors, average annual earnings rose, but at a considerably slower pace, about 18%. Of course, average hospitality earnings in 2017 were very low, at $18,570.

There are many reasons why wages in the industry have been so low: minimal entering skill requirements, the prevalence of part-time work, and up to recently, the relative abundance of workers. The dramatic increase in earnings likely can be traced to a severe drop of applicants, bidding up hourly wages. It is also likely that hours worked per week climbed.

To better understand the relatively low wages of hospitality establishments in the greater Tri-Cities, it might be good to digest a few characteristics of its workforce.

First, the ranks of its workers consist disproportionately of young people.

Census data show that the average share of the entire local work force taken by youth (ages 14-24) over the past five years has been about one out of every seven (14.4%).

The share of the hospitality workforce held by very young workers over the same period has been nearly three times that share, at 39%.

Inexperienced workers typically don’t claim the same wages as those who have been in the workforce for years.

Second, the local hospitality workforce skews Hispanic, according to the Census.

Over the past years, the share of Hispanic/Latino(a) workers in the local workforce has been about 28%. The share of Hispanics/Latino(as) in the hospitality workforce: 31%.

Language barriers and relatively low educational levels likely have contributed to a heavier weighting of this key population in hospitality services. It will be interesting to see whether the weighting disappears over time.

Third, the hospitality industry typically contends with high turnover. (This might be effect as well as cause.)

Data for the most recent four quarters of available data (2020 Q2 - 2021 Q1) reveal the average turnover rate in a given quarter for all sectors in the local economy was 10%.

Or, one out of every 10 workers changed jobs in the average 90-day period.

Among all sectors, hospitality produced the highest rate: 16%, or one out of every six workers changed jobs. Contrast this rate to that of the local finance-and-insurance sector, where quarterly turnover was a mere 6%.

2021 finished with local hospitality sales above those of the pre-pandemic peak in 2019, thanks to food-and-beverage establishments.

Hospitality sales this year should be higher yet.

Earnings by its workers should continue their upward climb. Yet, job counts still might not match those of 2019.

While sales headaches may be fading for these businesses, staff turnover still represents a challenge. Subsequent data will tell whether higher wages will bring down the high hospitality churn rate.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News Hospitality & Meetings

KEYWORDS august 2022