Home » St. Pat’s starts dual language program as concept gains statewide traction

St. Pat’s starts dual language program as concept gains statewide traction

September 12, 2022

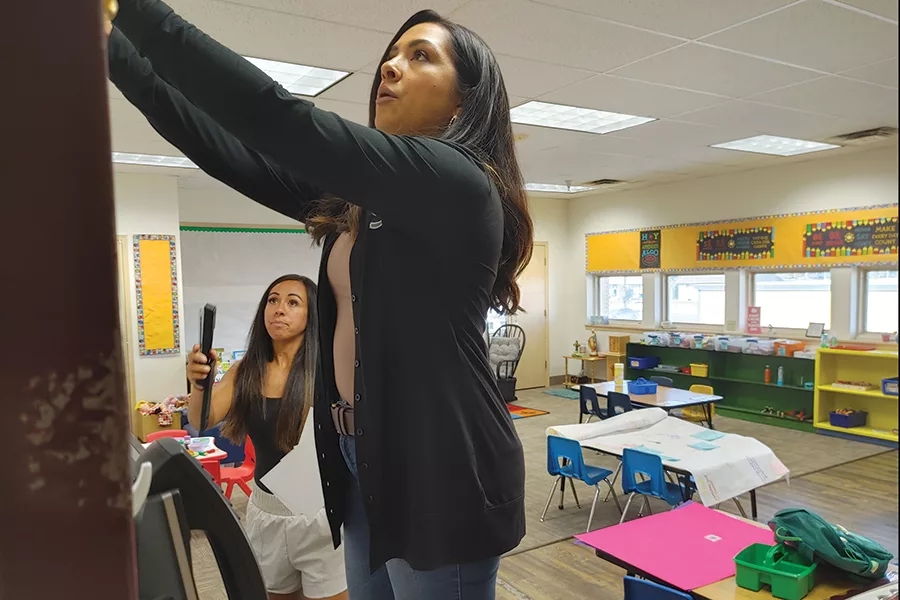

When school started at St. Patrick’s School in Pasco in late August, teachers Jessica Manueles and Ashley Wright greeted 20 or so children enrolled in kindergarten and prekindergarten classroom.

It was the start of something new at St. Patrick’s, a private school within the Catholic Diocese of Spokane’s St. Patrick Parish and led by Father Bob Turner.

Manueles spends half the day teaching in Spanish, and Wright spends half teaching in English.

The two teachers don’t repeat what the other already taught. Instead, they reinforce the subject matter across both languages, a dual language approach that promotes academic and language competency in both English and Spanish.

St. Patrick’s spent four years preparing its dual language education program and will expand to each grade, starting with prekindergarten and kindergarten.

It is one of a handful of schools – public or private – offering dual language education in the Tri-Cities and the only private one that does so. The move puts St. Patrick’s at the vanguard of a movement not only to teach languages, but to encourage literacy as well as fluency.

State initiative

The state of Washington plans to introduce dual language programs in every K-8 public school by the year 2040, Chris Reykdal, superintendent of public schools, announced in late August.

The Kennewick and Pasco school districts both offer Spanish-English dual language programs. Richland is evaluating the feasibility of a dual language program. Ty Beaver, spokesman, said Richland intends to begin offering dual language programs in the 2023-24 school year.

The OSPI initiative announced by Reykdal promises to dramatically increase access to dual language learning in all K-8 public schools. Dual language learning is distinct from the foreign language classes found in high schools or English as a Second Language programs.

In dual language classrooms, students learn in both languages and become proficient speakers as well as students in each.

“There’s an element of being bilingual. There’s an element of being biliterate,” said Principal Arlene Jones, referring to the ability to read, write, learn and speak in both languages.

Serving parish’s needs

St. Patrick’s began developing its program when it recognized that enrollment in its K-8 school wasn’t keeping up with the pace of growth of its massive parish. With 6,000 families, St. Patrick’s is among the largest and most diverse in the western U.S. And it serves Pasco, which is among the fastest-growing communities in Washington.

Jones estimates 85% of its parishioners speak Spanish in some fashion. The school serves about 150 students from a mix of economic backgrounds.

“When you have that big of a population that’s Spanish speaking and you have a school whose enrollment isn’t growing as fast as the parish, you have to ask if you are serving your population,” Jones said.

Seeing a need to educate children in a commonly spoken language prompted it to reach out to Boston College, a Jesuit school, to help form a program. The Boston College team performed a feasibility study that accounted for Pasco demographics and recommended the 50-50 model.

It will expand to a new grade as the first crop of students advances through the grades, until it is available in all grades. Students can sign up through first grade, which is a year later than most dual language programs. Too, it will admit students who transfer from comparable programs.

Waiting list

Parents quickly signed up. The first class is full and has a waiting list. The dual language class includes a mix of children who speak Spanish at home and English.

Jones said parents are interested in preparing their children for future careers and potential job opportunities open to people who speak two or more languages. Research links academic success to learning in two languages.

As a religious institution, St. Patrick’s is also interested in the whole child and in the idea of language serving as an equalizer.

“The first language you hear ‘I love you’ in embeds in you,” she said. “You can’t exclude that.”

Minoritized populations too often see their native tongues excluded in classrooms.

“You have to welcome people in the language they speak.”

St. Patrick’s is part of Boston College’s Two Way Immersion Network for Catholic schools, or TWIN. Wright, an English teacher, is a veteran educator who said she understands Spanish but is less comfortable speaking it.

The teaching team

Manueles is a bilingual and biliterate former administrative assistant who emerged as the ideal candidate to teach the Spanish half of the class.

She said Jones and other officials were impressed with her friendly demeanor, her gift for working with children and her ease in both languages.

Manueles recalled growing up speaking Spanish at home but being educated in English. She taught herself to read, write and study in Spanish – becoming biliterate on her own. She intends to pursue education credentials now that she is in a classroom.

When Boston College officials were in town to train the staff, Jones said it was clear Manueles was the ideal person to teach alongside Wright.

Manueles described the moment she felt the call as her “Holy Spirit moment,” a concept that was deeply meaningful to her faith.

As the teaching partners set up their classroom in late August, they split tasks and shared enthusiasm for the coming start of the year.

“We are a great team,” Wright said.

The program began with a single classroom, but Jones said the energy is infectious to the other classrooms in the building.

“Everybody recognizes we’re on a train that is bound for great things,” she said.

Jones said she’s pleased to see the state’s public school system embrace dual language education and hopes some dollars will follow pupils who attend private schools such as St. Patrick’s.

Her advice to education leaders faced with implementing dual language programs is to seek out the experts in their circles. For Catholic schools that is the TWIN program. For public schools, it is other public schools already offering the program.

State rollout

Under the plan announced by OSPI, dual language will be available in grades K-8 by 2040. Under the Reykdal’s plan, the Legislature would expand on its investment in dual language by adding $189 million in the 2023-25 budget cycle, with money earmarked to train teachers and establish curriculum.

Washington currently has 102 dual language programs offering Spanish, three offering Chinese-Mandarin, two offering Vietnamese and five offering tribal languages – Kalispel Salish, Lushootseed, Makah, Quileute and Quishootseed.

According to OSPI, the existing dual language programs serve 35,000 publish school students in 42 districts and state-tribal education compact schools.

Reykdal links student success to studying foreign languages.

“When young people become bilingual during the early grades, they have more cognitive flexibility and they perform better in school,” Reykdal said. “As our global economy changes and our world becomes increasingly international, dual language education must become a core opportunity for our students.”

Local News Education & Training

KEYWORDS september 2022