Home » Without people of color, there is no Tri-Cities economy

Without people of color, there is no Tri-Cities economy

April 12, 2023

Viewed from the perspective of one year to another, very little changes in a community’s demographics. Viewed from the perch of a decade or two, demographic change is usually easy to spot. So it is with race and ethnicity in the greater Tri-Cities.

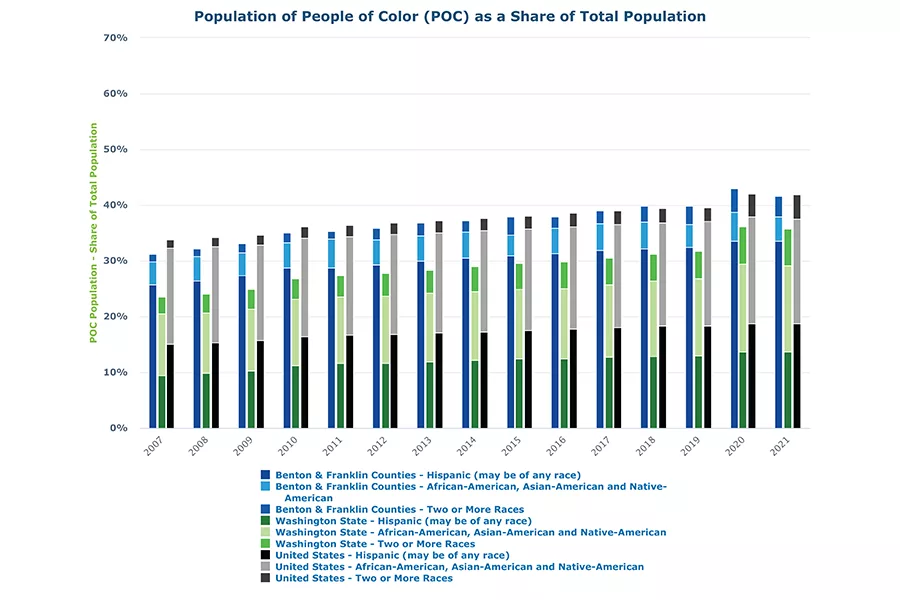

Consider the size of population of people of color in the two counties. In 2021, Census estimated it to be nearly 42% of all residents. In 2020, it was 43%. Statistically, that means no change.

A comparison of the present to the start of the series tracked in the Benton-Franklin Trends indicator comes to a different conclusion. In 2007, people of color claimed about 32% of total population. In the intervening 15 years, their share climbed by a full 10 percentage points. For 2021, Census estimates put the total non-white population in the greater Tri-Cities at slightly over 123,000.

A quick takeaway: Without the participation of people of color, the economy of the greater Tri-Cities simply wouldn’t move.

This changing face of the area should be obvious to residents or visitors. And at least every resident knows that the distribution of people of color among the three cities here is hardly uniform.

As the same indicator reveals, Richland’s 2021 population of people of color amounted to about 21% of its total. Across the river, Pasco’s share of people of color was nearly three times as high. The mix in Kennewick? About 41% of the total population.

As the Trends graph shows, the share of people of color in the area population is now about equal to its share nationwide. With the exception of Yakima County, this is a unique position for a Washington metro area. To no surprise, it is due to the outsized presence of the Hispanic/Latino population.

A consequence of such a strong presence of Hispanics/Latinos here is the overall age profile. In short, the greater Tri-Cities are very young. The area’s overall median age, estimated by Census at 34.6 years for 2021, is considerably lower than both Washington’s and the nation’s. This is nearly entirely due to Hispanics/Latinos.

For the two counties, their median age was estimated to be 23.5 years in 2021, a result nearly off the charts for the state’s metro areas.

Economic dividends – only for some?

If the Tri-Cities can keep most of its young people, this demographic uniqueness should pay dividends down the road. Hispanic/Latino entrants to the workforce should power further growth of an already strong local economy.

Nationally, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports the current labor force participation rate by Hispanic/Latinos at several percentage points higher than by the entire population, especially for men. While the BLS projects that all 2031 participation rates will be lower than today, Hispanic/Latinos will still be over-represented in the workforce.

But will the area’s people of color be able to reap the rewards of their larger presence in the workforce? If current employment patterns hold, likely not. The share of people of color in high-paying sectors is much lower than its overall average share in the workforce, about 41%.

For example, the sector “Professional, Scientific & Professional Services,” one of the area’s largest, reveals that only 25% of the jobs w–ere claimed by people of color in mid-year 2022. The sector’s average annual earnings in 2021: about $101,800.

Consider, too, the sector “Administrative and Waste Services.” Here, people of color claimed about 31% of its jobs at mid-year 2022. Average annual earnings for this sector in the two counties in 2021: $85,725.

On the other hand, 58% of all agriculture jobs in the two counties were held by people of color at mid-year 2022. Average annual earnings in 2021 for this sector: $35,275.

And consider that 46% of all jobs in the hospitality sector at mid-year 2022 in the greater Tri-Cities were claimed by people of color. Average annual earnings for this sector: a bit more than $24,560.

The overall average annual wage in the two counties in 2021? About $58,800.

Generally, local people of color earn much less than the average largely because of where they work.

The education challenge

For people of color in the greater Tri-Cities to participate fully in their own demographic dividend, they will need to find their way out of low-paying and into high-paying industries.

In most cases, that step up will only occur with greater training and education. At the moment, their march through institutions of post-secondary education is faltering.

A Trends indicator follows enrollment by all graduating high school seniors into higher education institutions, either two- or four-year.

The overall trajectory is not promising. It peaked in 2008, with 65% of area high school graduating seniors registered within a year at a four- or two-year college somewhere in the U.S. The latest data, from the class of 2021, show a sharp decline, even worse for students of color.

Consider college-going students from the area’s three largest school districts, using the largest group of students of color, Hispanics/Latinos.

For the Kennewick School District, the current (2021) overall share was 47%. For its Hispanic students, 43%.

For the Richland School District, the current overall share was 51%. Contrast that to the share of its Hispanic students, at 37%.

The table is a bit turned in the Pasco School District. Its college-going students in total amounted to a share of 35%, while that of its Hispanic students was 38%.

The 2021 results – for all seniors and for those of color – represent substantial declines from five years ago and certainly from the 2008 peak.

Undoubtedly, the full force of the pandemic was still reverberating for the class of 2021.

Let us hope that the decline is not permanent. Without further education, students of color will not be able to participate in what is likely a promising future for the greater Tri-Cities economy.

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Opinion Diversity

KEYWORDS april 2023