Home » Intervention necessary to improve Tri-City river health

Intervention necessary to improve Tri-City river health

May 11, 2023

Outsiders to the Tri-Cities often see an arid landscape with green life only where human hands have touched the earth. Locals, too, see their desert surroundings. But many view themselves as inhabitants of a riverine world. Two mighty rivers join south of Pasco and a significant river, the Yakima, enters the Columbia between Kennewick and Richland.

This identity is reflected in the convention center which goes by the moniker Three Rivers. The community’s treasure chest, 3 Rivers Community Foundation, also adopts the same name. Many other organizations and businesses appropriate the description in their names.

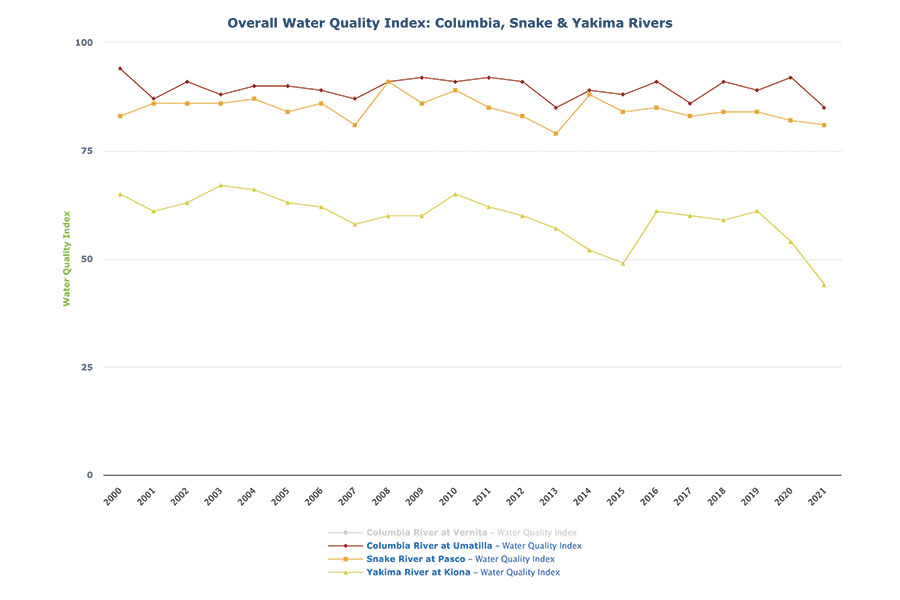

Yet all is not well for these ribbons of life that shape the identity of the Tri-Cities. This can be viewed in the accompanying Benton-Franklin Trends graph, “Overall Water Quality Index.” The index, or WQI, is produced by the Washington State Department of Ecology and combines several attributes of a healthy surface water, putting their scores into a unit-less (index) set of numbers.

Components include: turbidity, temperature, phosphorous (pH) levels, amount of fecal coliform bacteria, dissolved oxygen readings, among others. The components are sampled monthly, the data converted into sub-indices, then the sub-indices area combined to produce an annual average. One hundred is the maximum possible score. A reading above 80 rates water quality as “good,” or meeting expectations. A WQI reading of 40-79 indicates that the department has some concern. A score below 40 indicates the water body is of “highest concern.”

As we can observe, both the Columbia (at Umatilla) and the Snake (at Pasco) currently score in the “meeting expectations” range. WQI readings in 2021 for the two were 85 and 81, respectively. The same assessment, however, is not currently not true of the Yakima River at Kiona. Its 2021 WQI reading was 44, nearly in the red, or “highest concern” zone.

Plunging quality

Significantly, the WQI for the Yakima River has recently plunged. In 2019, its average score was 61. In the space of two years, its quality fell by nearly one third. What’s behind this dramatic decline? Rising temperatures.

Supporting detail from the state Department of Ecology put the WQI for temperature at 54 in 2020 and 32 in 2021. At those levels, the water is simply too warm for the health of the river’s flora and fauna.

Notably, warm temps are a lower river issue. Readings for the same years for the river at Cle Elum and Knob Hill (Yakima) were generally in the “meeting expectations” range.

The phosphorous WQI sub-index for the Yakima River at Kiona also has flashed yellow over these two years, with a value of 50 for both years. Phosphorous leads to accelerated growth of algae and plants, harming both vertebrate and invertebrate life. Sources include the underlying geology of the riverbed, but also wastewater plants, runoff from lawns and fields, failing septic systems and discharges from manure storage areas.

As with temperatures, high pH values have been a lower river phenomenon. For readings of the river taken in Cle Elum and Nob Hill, the phosphorous WQI sub-index values were all above 90.

While the drop-off in the water quality of the Yakima River has been pronounced recently, the long-term trend is one of decline. As the Trends graph shows, its WQI value at Kiona in 2000 was 65. Despite concerted efforts of the state and local officials to raise quality levels over the years, by 2019, the WQI had slipped to 61.

Declining trends

It is worthwhile noting that water quality of the other two rivers also has slipped over the same 20 years. The quality of the Snake River’s water at Pasco was roughly the same in 2021 as in 2000. The water quality of the Columbia, however, has declined from 94 to 85 over the same interval.

What to do to arrest the declines, especially in the Yakima? Efforts to remediate are ongoing and could fill the entire issue of this paper. Human intervention has been the cause for some (most?) of the impairment of water quality. Consequently, policies to boost water quality components such as phosphorous, dissolved oxygen, fecal coliform bacteria are likely to move the needle, if only slowly.

A more challenging push on the needle is posed by temperature. Rising air temperatures across the Inland Northwest do not bode well for traditional life in all our water bodies. Yet even here, some steps may offer improvement for the Yakima, such as flow maintenance or shading strategies. Let us hope that over the next decade, the trendline for this iconic river at least recovers to earlier levels. Might it also approach the water quality of its two larger neighbors?

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Environment Opinion

KEYWORDS may 2023