Home » Covid-19 has infected college-going behavior in the Tri-Cities

Covid-19 has infected college-going behavior in the Tri-Cities

September 14, 2023

The Covid-19 pandemic ushered in a skepticism of medicine and science among certain segments of society. It appears that it also has introduced a wariness of the value of post-secondary education.

A reluctance to pursue post-secondary education is more pronounced in the greater Tri-Cities than throughout the state.

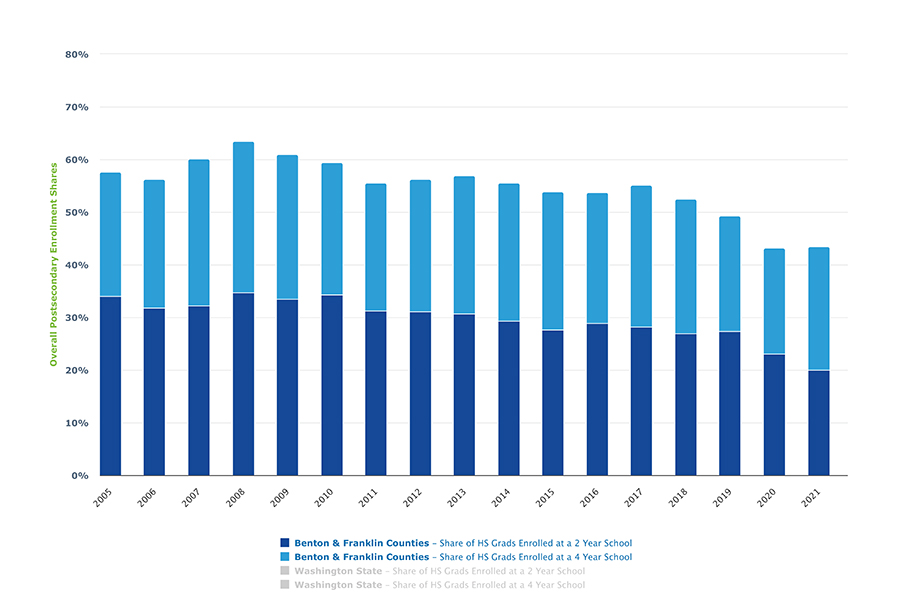

Benton-Franklin Trends compiles a measure produced by the Washington State Education and Research and Data Center (ERDC) on college-going behavior among high school seniors. The accompanying graph tracks this and is available here for online readers. Specifically, the measure arrives at the share of seniors who attend a two- or four-year institution of higher learning within one year of graduation. Those institutions can be in- or out-of-state and may be private or public.

The ERDC data reveals a startling fall-off in recent higher education attendance. The share of local high school seniors attending some form of higher education within a year of graduation was nearly 50% in 2019. Three years later, the share stood at 44%.

The drop here occurred exclusively in students attending two-year institutions. The share of those students declined from 27% to 20% between 2019-22. The share attending four-year institutions actually rose by 1.5 percentage points. A significant fraction of community college students, of course, continue their education at four-year schools.

Further, shares for both categories are lower here than Washington averages. For 2021, the share of local students attending two-year institutions was 1 percentage point lower than the Washington average. The contrast for high school seniors matriculating into four-year institutions was more dramatic: 31% across the state, versus 24% in Benton and Franklin counties.

The decline in college-going at the community college and trade school level is undoubtedly tied to the robust labor market. Average unemployment in the greater Tri-Cities, observable in Trends data, stood at 5.4% last year, versus 6.0% in 2019. Just as important, average annual earnings climbed a cumulative 14% between 2022 and 2019, faster than the 9% pace over the preceding four years.

As is often the case, differences lurk within the averages. Nationally, wage increases during and immediately following the pandemic in 2022 have been greater for occupations requiring modest training and education than for those requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher. The same is true here, as a look at wage gains by sector reveals.

Retail trade annual earnings jumped by 25% between 2019 and 2022, as Trends data reveals. Average annual earnings in hospitality (accommodations and food services) in Benton and Franklin counties climbed 23% and 19%, respectively. In contrast, average annual earnings in the high-paying sector professional and technical services rose 9% and 7%, respectively, in Benton and Franklin counties over the same period.

It is not surprising, then, that young people here have been drawn to jobs that offer the immediate gratification of a rapidly rising paycheck. But why has the fall-off in college-going been more pronounced here than throughout the state?

One answer lies in the composition of the area’s high school graduates. Increasingly, they are made up of students of color, more so than statewide. And these students may be responding to real-world signals about the premium for attending college.

In some startling new research, economists at the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank have produced national estimates of the college wage premium by race and ethnicity. Their measure is the ratio of average annual earnings of those with a four-year college degree to those whose highest degree is a high school diploma. (One can also calculate an analogous premium for holders of associate degrees.) It won’t surprise anyone that the premium is substantial. According to the study, it was about 75% in 2022.

That average, however, masks substantial variation by race and ethnicity. For Asian Americans, the most recent college premium was over 110%. On the other hand, the most recent college premium for Hispanics was slightly below 70%. The premia for Whites and Blacks lay close to the overall average.

The reasons for the disparities could be many, including the choice of academic major and the attainment of a post-graduate degree. If, for example, the share of Hispanic students choosing STEM fields of study is much lower than the share of Asian-American students, then earnings between the two college-educated groups will differ.

Another reason could lie in recent increases in wages in industries that have traditionally been populated by Hispanics. Everything else equal, those higher earnings will lower the premium ratio.

Recent declines in college-going, here and throughout the state, are actually a continuation of a multiyear trend. As the graph illustrates, college-going in the greater Tri-Cities peaked with the graduating class of 2008. Then, nearly 64% of all seniors were in a two- or four-year school within a year. The decline has affected both categories but two-year institutions harder, with a drop of the latter from 35% to 20%.

Let us hope that the recent allure of certain customer-facing jobs gives way to an appreciation of the longer-term benefits of acquiring some post-secondary education. That will be good for the Tri-Cities economy. It will also provide firmer footing to young people populating that economy.

D. Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends, the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Opinion Education & Training

KEYWORDS september 2023