Home » Pasco boy grows up to influence Hollywood cinematography

Pasco boy grows up to influence Hollywood cinematography

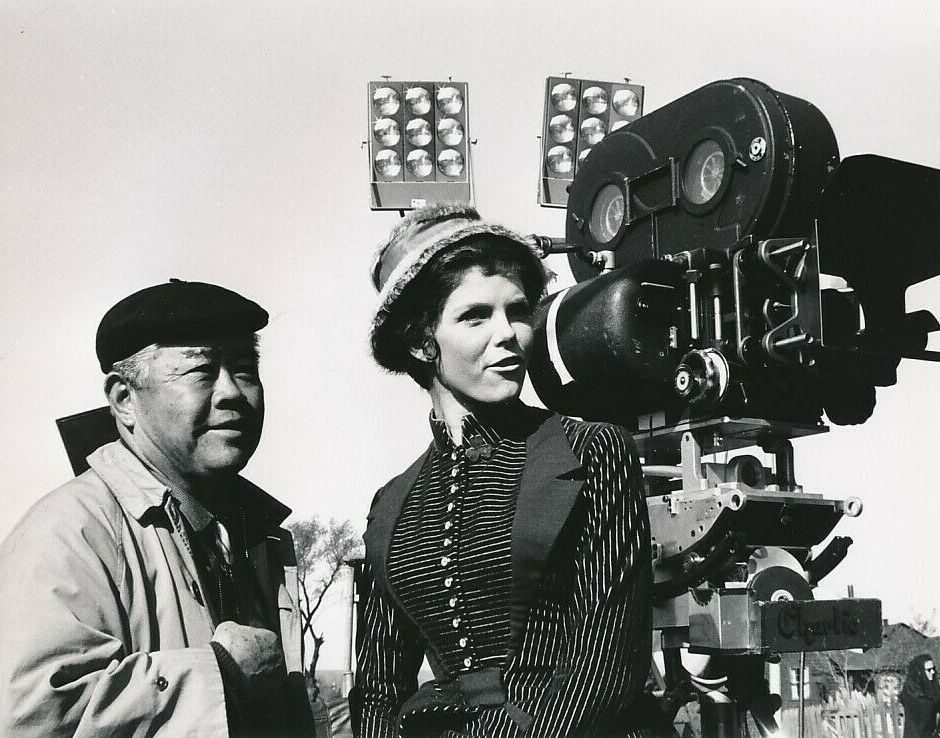

James Wong Howe and Samantha Eggar on set of The Molly Maguires, 1969.

Courtesy Wikimedia CommonsMarch 4, 2024

One day, so the story goes, a small Brownie camera was purchased in a downtown Pasco drug store.

It was given to a little boy by the name of Wong Tung Jim of Pasco, the son of a general store owner in the community.

The camera changed his life, and eventually led to major filming innovations on the sets of some of Hollywood’s legendary movies.

The boy grew up and professionally became known as James Wong Howe.

Howe will not be present when the 96th Academy Awards are aired live on March 10 as he died in 1976.

But by that time, he had become a legendary figure in Hollywood and had 10 times been nominated for an Academy Award for his work. He won twice.

His body of work spans more than 130 films.

His innovative techniques made him one of the most sought-after cinematographers in Hollywood, particularly during the 1930s and 1940s. He brought mastery to the use of shadows and innovation in deep-focus cinematography, allowing movie goers to enjoy both foregrounds and distant planes to remain in focus simultaneously.

Born in the Chinese province of Canton in 1899, he arrived in Pasco in 1904 where his father had earlier immigrated to work for the Northern Pacific Railroad. With the Brownie camera in hand, photography sparked his interest.

When Howe was a teenager his father died and he left Pasco to live with an uncle in Oregon, and ultimately ended up in Los Angeles working as a delivery boy and then as a busboy in a Beverly Hills hotel.

By a chance encounter, Howe came upon a Max Sennett short being filmed on the streets of Los Angeles, bringing him into contact with its cinematographer, and from that to a low-level job in the film lab of a studio. Sennett was the innovator of slapstick comedy. That parlayed him into a meeting with silent film director Cecil B. DeMille who liked Howe and made him a camera assistant.

Howe also began taking stills of stars in Hollywood.

While doing this work for silent film star Mary Miles Minter, he photographed her so her eyes appeared darker while she looked at a dark surface. She was so impressed Minter requested Howe to be director of photography on her next film, and his career as a cinematographer was launched.

James Wong Howe wins the Best Cinematography (black and white) Oscar for Rose Tattoo, 1956.

| Courtesy Wikimedia CommonsAccording to one account of his life, “Throughout his career, Howe retained a reputation for making actresses look their best through lighting alone.”

He struggled at first when “talkies” replaced silent films, but ultimately Howard Hawks, a legendary director/producer, selected Howe as cinematographer for his film, “The Criminal Code.” The two had met making “The Little American.” Director William K. Howard followed by selecting him as cinematographer for “Transatlantic.”

Howe first was nominated for an Academy Award for “Algiers” in 1938, and from then on he would be nominated for an Academy Award in every decade into the 1970s, including for his last picture, “Funny Lady,” the 1975 Barbra Streisand hit.

Others for which Howe was nominated but did not win included in 1940’s “Abe Lincoln in Illinois”; “Kings Row” starring future President Ronald Reagan in 1942; “The North Star” and “Air Force,” both from 1943; “The Old Man and the Sea” starring Spencer Tracy in 1958, “Seconds” in 1966, and then “Funny Lady.”

He won his first of two Academy Awards for “The Rose Tattoo” in 1955, a picture with a rather dark storyline and starred Anna Magnani who won that year’s best actress Oscar, plus Burt Lancaster, Jo Van Fleet and a host of other distinguished performers.

Howe’s second Oscar was for his work on “Hud,” the 1963 film with Paul Newman, Patricia Neal, Melvyn Douglas and Brandon de Wilde.

Howe became known for his innovations in lighting, using reflections, the use of unusual lenses and shooting techniques.

In the film “The Outrage,” he filmed a chase scene with the actors running in a circle. With his technique it appeared the chase was underway on film.

In shooting the Sean Connery film, “The Molly Maguires,” he shot one scene strictly using candles.

Howe, who stood a diminutive 5-foot-3, once had a short-lived career as a professional boxer.

He died in Hollywood of cancer and is buried in Westwood Memorial Park in Los Angeles.

Gale Metcalf of Kennewick is a lifelong Tri-Citian, retired Tri-City Herald employee and volunteer for the East Benton County Historical Museum. He writes the monthly history column.

Senior Times