Home » Desire to help those with addiction leads to new book debut, spurs recovery center

Desire to help those with addiction leads to new book debut, spurs recovery center

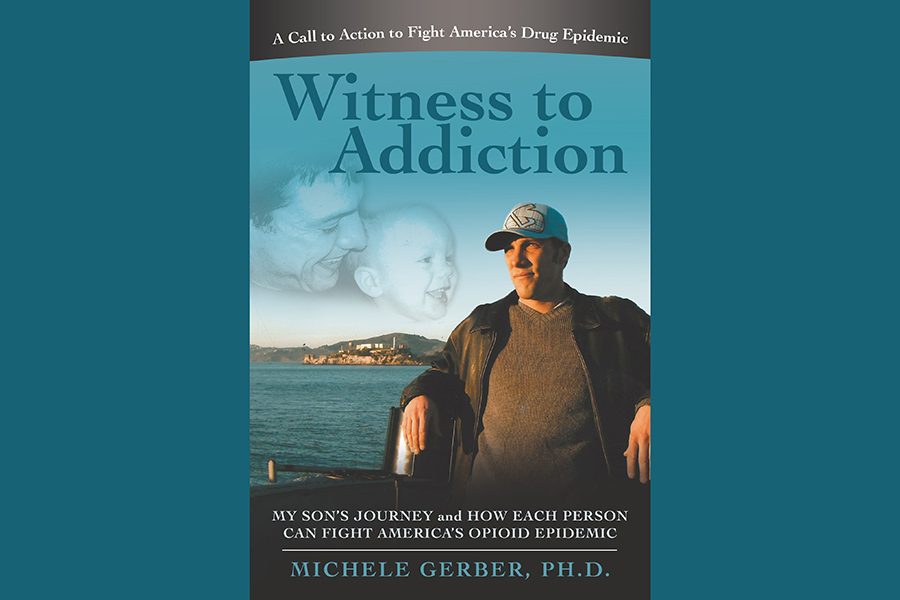

Michele Gerber, who lost her son, Jim, to addiction, shares his story in her new book, “Witness to Addiction,” which is available now through Westbow Press.

Michele GerberNovember 10, 2023

Michele Gerber’s son, Jim, gave the best bear hugs.

He was a tall, strong guy, and he’d lift his petite mother high in the air.

“I’d practically fly over his shoulder,” Gerber said with a laugh.

Jim has been gone nine years now, although he comes to life when Gerber tells stories about him – a handsome, gregarious, loving son and father who died at age 36 after years spent riding the roller coaster of opioid addiction. Gerber was there with him through it all, fighting to help him.

She’s still fighting now – to make sure others struggling in the same way find happier outcomes.

Gerber is a founder of the Benton Franklin Recovery Coalition, an advocacy group that’s played a key role in the behavioral health and substance use disorder recovery facility in the works in Kennewick.

And she’s written a new book, “Witness to Addiction: My Son’s Journey and How Each Person Can Fight America’s Opioid Epidemic,” that tells Jim’s story and shares the wisdom, insight and knowledge about addiction that she gained the hard way.

Her goal with the book is to enlighten and empower.

“The idea is to give tools and actions that every person can use,” Gerber said. “I don’t believe this can be solved by law enforcement, drug interdiction, so-called supply side. Those are things we ought to vote for and work on, but I don’t think they alone can do it. This book is to empower every person.”

A difficult loss

Jim first experimented with drugs as a teen. Then after high school, he moved to Sun Valley, Idaho, and worked as a snowboard instructor and chairlift operator. He became addicted to opioids after taking pain medication for an injury, although he didn’t initially recognize his addiction.

“He came home for a month (to visit). Afterward he said, ‘I was happy to be home, but I was depressed and had a cold and kind of a small flu.’ That was withdrawal. He didn’t realize it,” Gerber said.

“Later, when he was in treatment and he wrote journals, he talked about that – how it could sneak up on a person. Many people he knew who were addicted didn’t know they were addicted,” Gerber said.

She hopes “Witness to Addiction” will help readers spot the signs. Too often, addiction is viewed as shameful – a stigma that makes it harder to seek help, Gerber said. “But we have a saying that it’s a disease not a disgrace. It’s a medical issue not a moral issue. It’s a sickness, not a sin,” she said.

It’s also an epidemic. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reported in 2022 that 20.4 million people in the United States were diagnosed with substance use disorder during the past year.

Of those, only 10.3% received treatment.

More than 106,000 people in the U.S. died from a drug-involved overdose in 2021, the agency reported.

Gerber helped start the Benton Franklin Recovery Coalition about five years ago, after Jim’s death. She was joined in the effort by other parents who lost children to addiction, plus people in recovery themselves and a treatment counselor. They found allies in the law enforcement, the medical and faith communities and others, and the group has become the largest recovery coalition in Washington.

Gerber and her crew began lobbying for a recovery facility in the Tri-Cities – working with elected officials, making trips to Olympia and otherwise raising awareness about the need.

While the Tri-Cities area has more than 300,000 residents and counting, it doesn’t have in-patient addiction treatment. It’s the only major metro area in the state without such a facility.

However, that’s about to change.

Recovery center on the way

Benton County has purchased land in Kennewick – including a former Welch’s Grape Juice warehouse and the old Kennewick General Hospital building – for a behavioral health recovery center.

The center will serve the greater Tri-Cities area, helping people who are experiencing mental health crisis and those dealing with substance use disorder. It’s expected to open in 2025.

The former Welch’s warehouse on East Bruneau Avenue will be transformed into a crisis relief center, crisis stabilization unit and secure withdrawal management unit. The latter two units will have 16 beds each, while the crisis relief center will have a different configuration.

And the former Kennewick General Hospital building on South Auburn Street will be home to a 16-bed residential facility for people dealing with substance use disorder.

Other services, such as transitional or recovery housing, could be offered in the future.

A design-build team that includes Bouten Construction and NAC Architecture is in place.

“We are in what’s called a validation phase. That’s where we sit down with the design team and figure out how many rooms we need and what types of rooms we need and what size they need to be. We’re starting to work on figuring out how to fit the different programs in the two spaces we have. That will lead to a full design of the project. They’ll start construction when the design is about 30 to 40% complete,” said Matt Rasmussen, deputy county administrator.

The county is negotiating with Comprehensive Healthcare in Yakima to operate the center.

Rasmussen said the need for a recovery center in the community is clear.

“We’ve seen over time that there’s a big cost in not managing people who are having mental health or substance use issues... There was a surgeon general’s report probably six or seven years ago that figured if you spent $1 on behavioral health care you would ultimately save $7 in other community costs,” Rasmussen said. “Michele and her group – they are really passionate, they have a lot of lived experience and they really helped drive the point home of why this is important, and then the county helped step in because this is really better for the community.”

The two properties cost about $5.4 million total, paid for with a combination of state grant and local county dollars. County officials are still developing the final budget, but the last estimate put the construction cost at about $24 million, to be paid for with a mix of funding, including state and federal grants, Covid-19 response funds and money from the one-tenth of 1% sales tax increase for mental health services that took effect in Benton and Franklin counties last year.

That sales tax also will pay for operations of the recovery center.

'I hope he's proud'

Rasmussen called Gerber, “an amazing person,” and said he’s been inspired by her story.

Gerber hopes others will feel inspired in the same way when they read “Witness to Addiction.” The book is available now through Westbow Press, and she plans to offer book signing events locally.

Gerber, who holds a doctorate in history and worked for two decades as the Hanford site historian, previously penned the popular tome, “On the Home Front: The Cold War Legacy of the Hanford Nuclear Site.” But “Witness to Addiction” is by far her most personal book.

She’s excited about its debut, and she’s excited about the recovery center opening its doors.

It’s bittersweet. She misses her son and his bear hugs. She misses his smile and his laugh.

He had a big personality and people were drawn to him. He cared about others deeply.

He was open and brave. When he realized he was addicted to opioids, he reached out for help.

Gerber believes he’d be glad to know help is on the way for others in the Tri-Cities area and beyond, thanks to his mom. “I hope he’s proud of me,” Gerber said. “I have a strong Christian faith, so I believe he knows what’s going on, that he can see it. I know he would want to help people.”

“Witness to Addiction” is available at westbowpress.com, Amazon and at local bookstores.

Go to: michelegerberauthor.com.

Book signing events

- Dec. 3: 3 p.m., Richland Public Library, 955 Northgate Drive.

- Dec. 9: 1-3 p.m., Wisdom Books, 6501 Crosswind Blvd., Suite A, near Best Buy in Kennewick.

- Jan. 6: Noon, Barnes & Noble, Columbia Center mall, Kennewick.

Local News

KEYWORDS november 2023