Home » A town, a dream, a $10,000 donation: How Pasco got its Carnegie library

A town, a dream, a $10,000 donation: How Pasco got its Carnegie library

June 3, 2024

Andrew Carnegie once was denied admission to a community library because he was too poor.

He grew up to become the richest man in the world.

So, he built a library.

Actually, he built 1,679 new libraries in cities and towns throughout the U.S., and 2,509 worldwide between 1883 and 1929, spending nearly $60 million to do so.

Carnegie libraries became an institutional part of American history, a legacy of learning through free access to books.

Pasco joined the Carnegie family of libraries 113 years ago.

It was one of 43 built in Washington state, including those in Walla Walla, Sunnyside and Prosser.

About 800 of the nearly 1,700 built in the U.S. are still used as public libraries.

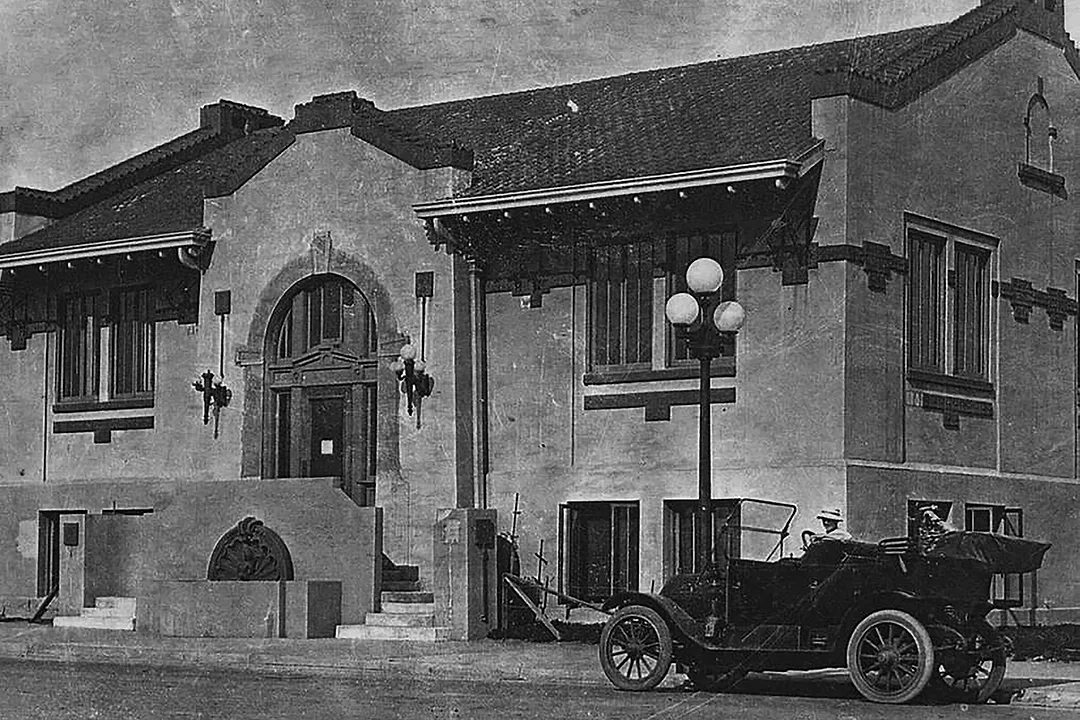

On June 30, 1911, the Pasco Carnegie Library was dedicated at 305 N. Fourth Ave. in downtown Pasco.

The building dedication began at 8:30 p.m. in the new basement meeting room, with piano solos and singing. About 200 people attended.

Mayor William T. Gray, master of ceremonies, declared the library officially open after noting Pasco’s growth had made it possible for the community to receive a Carnegie endowment.

The new library opened with 1,270 books.

Walter T. Hicks, library board president, also spoke, paying tribute to Carnegie, and noting that civic leader B.B. Horrigan had been instrumental in making the library possible. His efforts included a personal meeting with the famous philanthropist.

Launching a library

More than a year earlier, on Feb. 17, 1910, the Pasco City Council voted to buy land for the library from a Walla Walla man, a $1,000 expenditure.

A stipulation of the Carnegie endowment was that a municipality had to own the land the library was to be built on, with land for expansion if necessary. Taxpayer money also had to be available for salaries, maintenance and book purchases.

On April 5, 1910, the Pasco City Council passed an ordinance officially naming the building the Carnegie Public Library.

A five-member library board was established by the ordinance, which authorized the mayor to select the board.

The first board members, appointed by Mayor Gray, were Bernice Horrigan, Patrick Lenard, Maggie Page, Alice D. Jahnke and Hicks, who became the board president.

A two-story Spanish-style building with a terra cotta roof was designed and built, offering a main floor for books, magazines and newspapers. A basement was installed for community activities.

Construction cost $9,498, while necessary equipment came in at $2,500.

Carnegie had donated $10,000 to the city.

Replacement library

In April 1962, a new Pasco library opened at 1320 W. Hopkins St., replacing the 51-year-old Carnegie Library, after voters passed a $325,000 bond in 1960 for a replacement library.

Dedicating the new library were Horrigan, and Edna Linbarger, a retired librarian. Horrigan had served in the state Legislature and was a Superior Court judge for Benton, Franklin and Adams counties.

The old Carnegie Library ultimately fell into disrepair until a cadre of volunteers representing the Franklin County Historical Society restored it.

Today it is one of Pasco’s most historical and noteworthy buildings and serves as the Franklin County Historical Society Museum.

Carnegie’s legacy

Carnegie was a 17-year-old laborer oiling machines at a textile mill in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, when he sought to improve himself by visiting the local library which required a “subscription” costing $2.

A letter he sent to the library administrator for access to the museum fell on deaf ears. Only apprentices and unemployed men were allowed, he was told.

He then sent his letter to The Pittsburgh Dispatch newspaper, forcing the administrator’s hand and leading to library privileges, as well as for workers and not just apprentices.

And it was free.

When he began building his public libraries, Carnegie was cognizant of the segregation existing in many parts of the South. He built separate Carnegie libraries specifically for Black people so they would not be denied the same access.

His Carnegie Library in Washington, D.C., which opened in 1903 and cost $300,000, was open to anyone from the beginning. Black citizens said that for years it was the only downtown Washington, D.C., building in which they could use the restrooms.

The words, “Science, Poetry, and History,” are inscribed above its entry, and the library was said to be “dedicated to the diffusion of knowledge.”

The industrialist was described as “ruthless” by many in building his wealth but he gave away 90% of his estimated half-billion dollar fortune to many varied philanthropic causes, not just libraries.

He was once quoted as saying: “A man who dies rich dies in disgrace.”

Gale Metcalf of Kennewick is a lifelong Tri-Citian, retired Tri-City Herald employee and volunteer for the East Benton County Historical Museum. He writes the monthly history column.

Senior Times

KEYWORDS June 2024