Home » Hospital grows from farmhouse to regional medical center

Hospital grows from farmhouse to regional medical center

This summer marks Kadlec's 80th anniversary

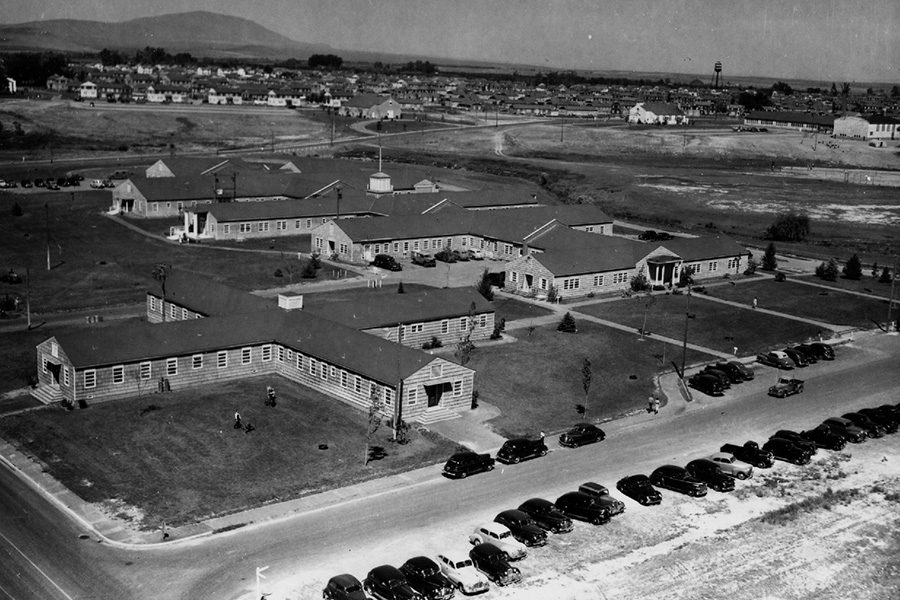

A well-staffed and -equipped medical and dental clinic, foreground, and hospital, background, were among the new public facilities provided to take care of the industrial requirements of the Hanford atomic plant, as well as to serve the essential needs of the Richland community, where the population increased during the war from about 250 to 15,000.

September 3, 2024

When the top-secret Manhattan Project got underway early in World War II and arrived at Hanford, it needed a place to take care of the medical needs of its growing number of workers.

It got one right away – in an existing farmhouse – but it was not quite sufficient for Richland, which had exploded from a village-like community of fewer than a thousand or so residents, to an ultimate peak population of an estimated 50,000.

Services got a little better when in June 1943 medical staff and equipment moved from the farmhouse into one of the women’s barracks.

A 10-bed treatment area was created.

It's a far cry from what today is known as Kadlec Regional Medical Center.

This summer marks Kadlec’s 80th anniversary.

It opened in the summer of 1944, just months after construction began in January through the combined efforts of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and DuPont, Hanford’s prime contractor.

Kadlec’s namesake

This summer also commemorates 80 years since the first person died at Kadlec.

Lt. Col. Harry Rubens Kadlec died July 2, 1944.

He was deputy area engineer and chief of construction for the Corps of Engineers on the Hanford project. Friends said he “worked himself to death” with his unrelenting efforts directed at building facilities at Hanford.

The lieutenant colonel suffered a heart attack and was rushed to the new hospital.

Eight days after his death, on July 10, 1944, the new Richland hospital was renamed Kadlec Hospital in his honor. Flags were lowered to half-staff, and services were held at Richland High School.

He was a popular leader on the Hanford site and was described as “a key figure on the project.”

Less than two months after his death, President Theodore Roosevelt, through the War Department, presented Kadlec the Legion of Merit award.

Kadlec is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

His military career began with his enlistment as a private in the Illinois National Guard cavalry on Dec. 2, 1913. He served in World War I through the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, and returned to the U.S. on Dec. 31, 1918, to enter the officers’ Reserve Corps of the Army.

Prior to America’s entry into World War II with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, to his assignment in helping build the Hanford complex, Kadlec was involved in five major Army construction projects: the Detroit Arsenal, Wabash River Ordnance Works, Lake Ontario Ordnance Works, Rocky Mountain Arsenal and the Kankakee Ordnance Works.

When the new hospital opened on the site that is now the Corrado Medical Building near the current hospital, it was a 55,000-square-foot one-story building.

The hospital included a central hall and various wings extending off the hall. It comprised 91 rooms, capable of holding 115 patients. A separate medical-dental building was built for dental and outpatient care, along with other services and two separate locations provided 20 isolation beds.

The original staff was overwhelmed. It comprised two doctors, five nurses, a part-time surgeon, and a pharmacist, not counting the superintendent and the assistant superintendent. All medical services had to be provided by this small team, including employee physicals, dentistry and public health.

It was soon apparent more help was needed, and a year after the hospital opened, it staff grew to 117 people.

The maternity wing started out as one delivery room with six beds and accompanying bassinets but was soon expanding with the frequency of babies being born there.

The national average for births in 1946 was 20 births per 1,000. Richland led the nation with 35 births per 1,000 people.

Babies and military secrets

The number of babies born at Kadlec was considered a military secret because the U.S. government didn’t want Germany or Japan to learn the number, fearing it might give them “a clue to the size of the Hanford workforce.”

Kadlec Hospital began as what was called a “closed facility.” Services were provided only to Hanford employees or their families, and to those living within the boundaries of Richland, which had been taken over and was being run by the federal government.

The first year, Kadlec served 3,153 patients.

In the beginning, it was difficult to obtain many essentials to equip the hospital. Kadlec’s auxiliary threw itself into the effort, making and repairing linens, sewing and creating other needed items.

When the federal government returned Richland back to civilian control under the Community Disposal Act passed by Congress, “Kadlec was the first major community service unit to be given to the citizens for independent operation.”

Gale Metcalf of Kennewick is a lifelong Tri-Citian, retired Tri-City Herald employee and volunteer for the East Benton County Historical Museum. He writes the monthly history column.

Senior Times

KEYWORDS September 2024

Related Articles

Related Products