Home » Meet the architectural gems of the Tri-Cities

Meet the architectural gems of the Tri-Cities

January 14, 2020

Michael Marley recalls when Tri-City school officials cautioned architects to avoid anything fanciful in their designs for new buildings.

Districts need voter approval to raise taxes to build and remodel schools. They feared “fancy” would come across as “wasteful.”

Decision-makers relied on plain buildings to convey stability and frugality, said Marley, principal with CKJT Architects, a Kennewick firm focused on public sector projects.

It’s an ethos that informed much of the region’s development but obscures the architectural gems that dot the community.

The Tri-Cities Area Journal of Business invited local architects to share their favorite examples. Most shrugged.

“My favorite is the building I’m working on at the moment,” one said.

“I don’t have a favorite Tri-City building,” said another.

Design takes a front seat

But there are gems, and Marley believes the list is growing.

Schools and other clients are more likely to aim for buildings the community can be proud of. It’s OK for a school to look nice, he said, citing Kennewick’s Eastgate and Westgate elementary schools as examples of changes in how buildings get designed.

Eastgate opened on East 10th Avenue in 2015 and Westgate on West Fourth Avenue two years later. CKJT wasn’t involved, but Marley said both are well massed, giving a sense of balance between form and function.

“It’s getting better. We’re starting to do better,” he said.

Marley’s top picks for the Tri-Cities’ “hidden” gems include the Port of Pasco’s $42 million project to renovate the passenger terminal at the Tri-Cities Airport in Pasco, and two Kennewick projects – Parish of the Holy Spirit Catholic Church and the HAPO Business Complex, commonly referred to as the flashcube building.

To the casual passerby, the flashcube is a glass box filled with offices with an outsized electronic reader board attached to one side. But Marley remembers what the neighborhood looked like when it opened in 1978 at the intersection of West Clearwater Avenue and Columbia Center Boulevard.

Both roads turned to dirt at the intersection. The four-story office building neighbored a manufactured home park and undeveloped land. It was a striking addition to the landscape, he said.

The yellow-roofed Parish of the Holy Spirit Catholic Church, just east of the flashcube, is another favorite for its geometric form and flexible interior.

Gem status

Design West Architects P.A. in Kennewick nominated the Columbia Basin College planetarium, the Washington State University Wine Science building and the cable bridge for “gem” status.

The planetarium houses the largest planetarium theater in the region while the wine science building combines teaching space with a full production winery.

The cable bridge, officially known as the Ed Hendler Bridge for the Pasco mayor that championed it, is arguably the area’s most iconic structure.

It was the first major cable-stayed bridge built in the U.S., and it attracted attention when it opened 42 years ago.

It won the first-ever presidential award for excellence in design from a jury led by the late I.M. Pei. Jurors called it a technical achievement and a work of art.

A history of excellence

Michael Houser, Washington’s architectural historian, said the Mid-Columbia has a long history of excellence in design.

The Carnegie Library, now the Franklin County Historical Society Museum in downtown Pasco, opened in 1911.

The Franklin County Courthouse, constructed in 1912-13 with a stunning 26-foot rotunda, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, the same year the cable bridge opened.

Houser’s job includes cataloging buildings and structures of interest across Washington. With little prompting, he identified more than two dozen structures in Kennewick, Richland and Pasco that have his attention.

“I love the Tri-Cities,” he said.

A sample of the region’s architectural gems

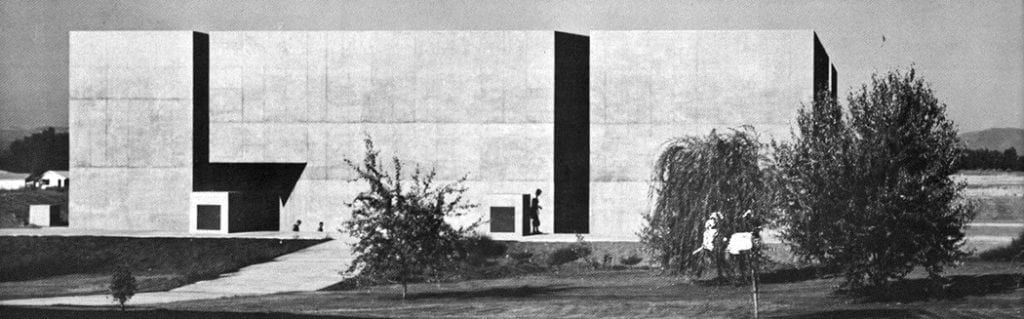

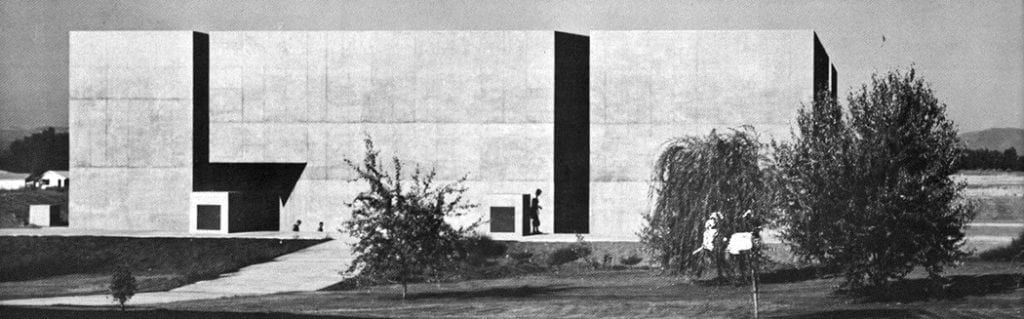

CBC Arts and Music building

Arts & Music Building, Columbia Basin College, Pasco.

It is Houser’s favorite building in the Tri-Cities in part because its future is clouded.

The Washington State Community and Technical College System included $2.3 million to design a replacement in the capital budget it submitted to the 2020 Legislature.

Houser said it would be a shame to lose an admittedly stark building that broke the rules. The Spokane chapter of the American Institute of Architects honored it in 1977.

The National AIA followed suit in 1978.

Old National Bank building

The former bank branch at 202 N. 10th in Pasco, is another standout.

Now a store, its Mid-Century stylings stand out in a neighborhood that includes a school, modest homes and small businesses.

Concrete piers support a series of pyramid-shaped roofs and floor-to-ceiling glass walls.

“If you go inside, it’s even more interesting,” Houser said.

The numbers one through 10 written in Arabic, Chinese, English, Greek, Indian, Roman and other languages are carved into the wall.

Architectural West magazine profiled the branch building in a 1967 publication.

Carnegie Library

Pasco’s Carnegie Library opened in 1911, one of the 2,500 funded by steel and rail magnate Andrew Carnegie between roughly 1880 and 1930.

Carnegie set guidelines for size and function but left it to local architects to work out the details.

Carnegie libraries dot the landscape, but no two are exactly alike. Pasco’s operated as a library until a new one opened in 1962.

The Franklin County Historical Society converted the old building to its present museum.

Mid-Century Richland

Richland, which separated from the U.S. Department of Energy when it incorporated in 1955, is stocked with mid-century gems. “Any time you’re in Richland, you’re talking about post-World War II” stuff, Houser said.

Some of his Richland favorites are the city-owned water plant on Saint Street, which sports a striking blue and yellow façade, Richland Lutheran Church’s mushroom-shaped (or folded plate) roof and the former TruStone Inc. building.

TruStone is long gone but its roof became the fingernail stage at Howard Amon Park.

Honorable mentions

Houser also highlighted the Lewis Street underpass in Pasco, the historic alphabet houses in Richland and the 3030 West Clearwater Business Center, an angular structure with echoes of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the name of Parish of the Holy Spirit Catholic Church. 1/16/20

Architecture & Engineering

KEYWORDS january 2020